The Supreme Court decision in United States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163 (1965), represented a significant step in the expansion of the concept of religion under the First Amendment.

At issue was whether belief in a Supreme Being was required to be a conscientious objector and, by implication, protected under the First Amendment’s establishment and free exercise clauses. The Court heard Seeger as a consolidated case involving two other applicants for conscientious objector status.

Daniel Seeger applied for conscientious objector status with draft board

Seeger arose during the Vietnam War when an applicant for conscientious objector status, Daniel Andrew Seeger, brought a claim that the First Amendment’s establishment and free exercise clauses had been violated by a draft board’s refusal to grant his application. The Universal Military Training and Service Act exempted those from service who by virtue of their “religious training and belief” were opposed to war.

The selective service application completed by Seeger contained the statement “I am, by reason of my religious training and belief, conscientiously opposed to participation in war in any form.” Seeger placed quotation marks around “religious” and crossed out “training and.” When questioned, Seeger could not confirm that he believed in a Supreme Being but stated that he thought killing in war was morally wrong.

Seeger’s draft board denied his application because his objection was not based on a belief in a Supreme Being. He was eventually convicted for not refusing to be inducted into the armed forces.

Supreme Court adopts more expansive understanding of religious beliefs

In its ruling on the case, the Supreme Court adopted a test for religious belief that asks whether a belief has the same significance in a person’s life that clearly traditional religious belief would have.

The Court cited the expansive understanding of religion in the writings of theologians, noting in particular the work of Paul Tillich, who wrote that religion should be thought to encompass all “ultimate concerns” of people, whether or not expressed in traditionally religious language, such as through belief in God.

The Court rejected a distinction between beliefs derived externally (that is, from a religious tradition) and internally (that is, from purely personal beliefs). In Seeger the Court moved definitively away from requiring theistic belief — that is, belief in a Supreme Being — as a necessary condition for a belief to be religious under the First Amendment.

The Court advanced the Seeger holding further in Welsh v. United States (1970), a case that also involved an application for conscientious objector status. In Welsh the Court made explicit its rejection of a distinction between personal belief and affiliation with, or practice of, a recognized religious tradition.

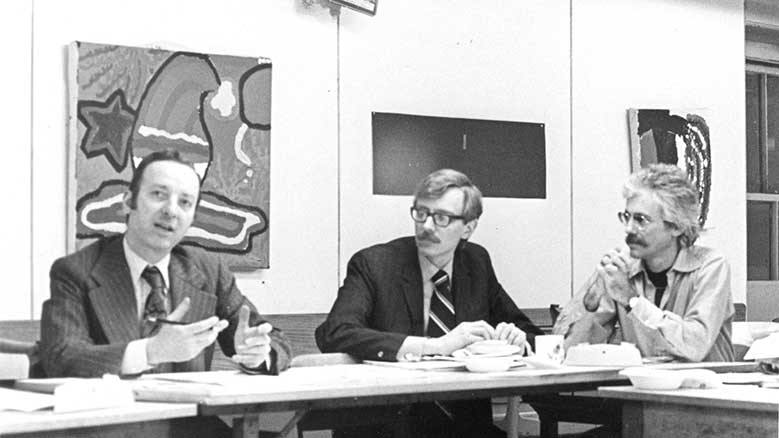

In 2017, Seeger reflects on his conscientious objector case

In a 2017 essay on the case published by Friends Journal, Seeger reflected that when he “wrote to my draft board requesting exemption from military service because of my deeply held pacifist convictions, I was an unchurched youth, having drifted away from the Roman Catholicism of my family and into agnosticism…”

“The First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States guarantees citizens freedom of religion. It stipulates that the government shall not interfere with the free exercise of religious practice, and it also proscribes the government from behaving in a way that prefers, or ‘establishes,’ a particular faith or group of faiths over others. The main argument in my defense was that Congress, in requiring affirmative belief in a Supreme Being as a prerequisite for exemption from military service, was preferring people of some religious beliefs over people of other religious beliefs or with no religious belief, thereby violating the “disestablishment clause” of the First Amendment to the Constitution…

“Fifty-two years after the Supreme Court decision, I remain convinced that we are better off acknowledging that we face great and awesome mysteries about our origins and about life and death than we are by claiming to know too much. We can develop a reverence for what is sacred without making extravagant dogmatic claims—claims that always flaunt and fail. While I have become an avid reader of devotional literature from Christian and other traditions and have met many God-fearing people whose purity of spirit has been truly uplifting, I am also increasingly wary of the dangers of religious fanaticism, an age-old problem in every spiritual culture and one which manifests itself with particular virulence today.”

This article was published in 2009 while Kevin R. Davis was Associate General Counsel at Vanderbilt University. He is now Senior Counsel at HealthTrust Purchasing Group.