In California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567 (2000), the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional a state law that changed California political primaries into “open” primaries. In open primaries, individuals of any political affiliation can vote.

The Court based its decision on the First Amendment freedom of association.

Political parties have generally had freedom to govern their affairs

Political parties generally have broad political discretion and freedom to govern their internal affairs.

For example, in Tashjian v. Republican Party of Connecticut (1986), the Court invalidated a state primary law that prevented a party from inviting independent voters to participate in its primaries. Yet in other cases, for example, Smith v. Alwright (1944), the Court limited parties’ use of racial criteria.

California changes law to create a open primaries

Jones presented the Supreme Court with the issue of whether political parties must open their primaries to anyone who wants to participate.

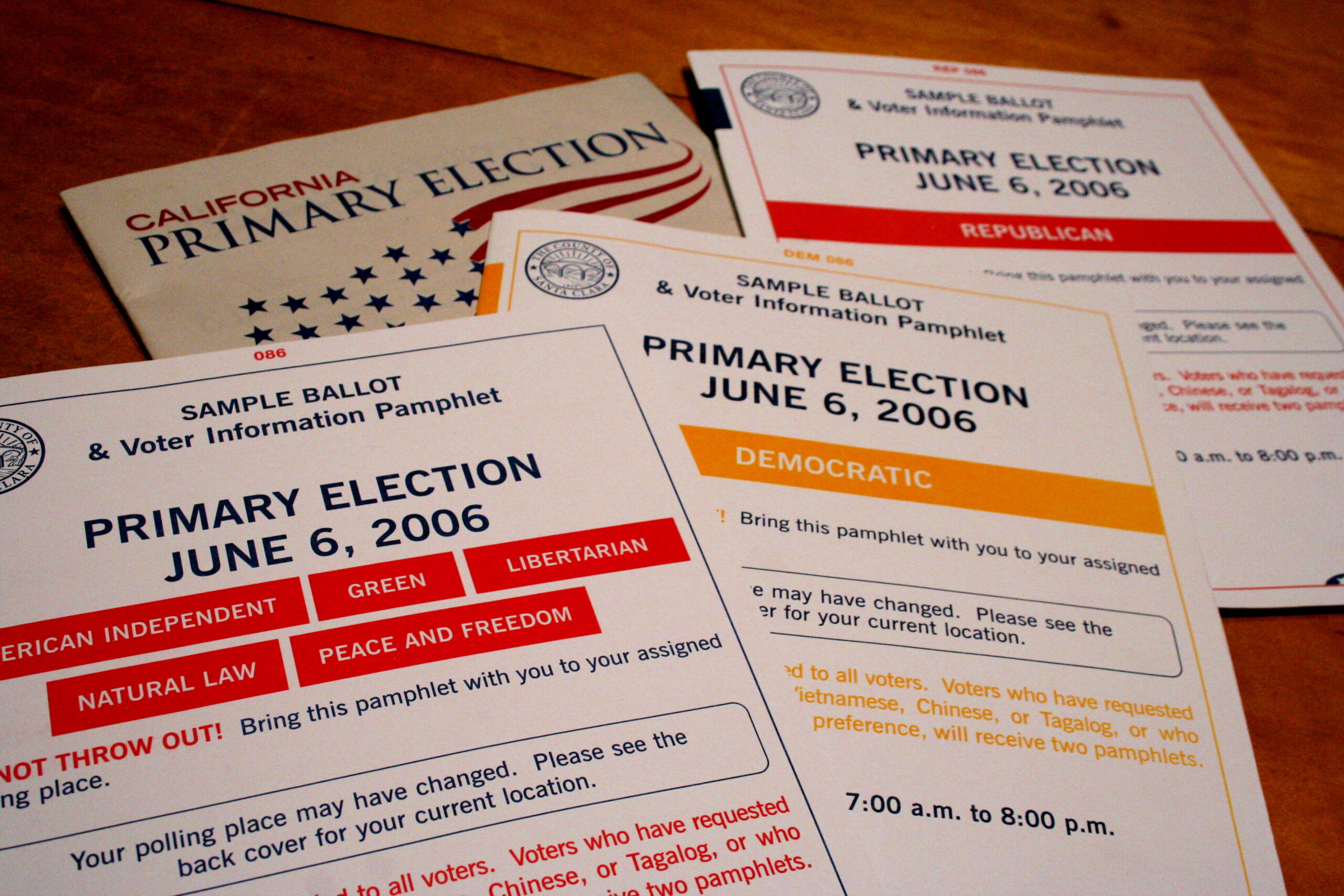

Until 1996 California had had a “closed” primary system, in which individuals can participate only if they have indicated a party affiliation when they register to vote. In other words, to vote in the Republican primary, an individual would need to be registered as affiliated with the Republican Party.

In 1996 California voters adopted Proposition 198, creating an “open” primary in their state. The law provided that “[a]ll persons entitled to vote, including those not affiliated with any political party, shall have the right to vote … for any candidate regardless of the candidate’s political affiliation.”

The California Democratic Party, the California Republican Party, the Libertarian Party of California, and the Peace and Freedom Party all challenged the law as a violation of their First Amendment rights.

A federal district court ruled that the law’s infringement upon the associational rights of the parties was not severe enough to invalidate the law. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed, but the Supreme Court reversed in a 7-2 vote.

Court struck down law on First Amendment grounds

Writing for the Court, Justice Antonin Scalia stated that although the government may regulate some of the structure of parties, the issue of how and whom parties select to be their candidates is not wholly a public affair.

According to the Court, the First Amendment protects the internal affairs of a party from state regulation. Drawing upon Tashjian and other cases, Scalia noted that freedom of association included the choice of whom to associate with as well as whom not to associate with, leaving parties free to decide whether to open up their primaries to outsiders and to control the selection of their nominees. The determining of a candidate for the party is an important policy decision that the First Amendment protects. Therefore Proposition 198 violated the associational rights of parties.

Dissenters said First Amendment rights were not absolute

In dissent, Justices John Paul Stevens and Ruth Bader Ginsburg agreed with the lower courts that the First Amendment rights of parties were not absolute. Drawing upon Alwright and other such cases, they contended that elections and primaries were not private affairs and could be subject to such regulations as Proposition 198. Laws that allow for open primaries do not inhibit freedom of association but instead facilitate it by opening more avenues for political participation.

Later decision may provide more room for state regulation

Despite the importance of the Jones decision in defending the freedom of association rights of political parties against government regulation, in Washington State Grange v. Washington State Republican Party (2008) the Court upheld a blanket primary system.

In contrast to California, in Washington state the primary system allows voters to select their choice for each office regardless of their or the candidates’ party affiliation; the overall top vote getters for each office are then put on the general ballot.

Writing for the Court, Justice Clarence Thomas noted that under the Washington system, the primaries do not determine the party nominees (unlike under the California system). Thus, Washington’s blanket primary does not interfere with party associational rights as did the California process.

In light of the Washington State Grange decision, states may be permitted to regulate internal party affairs more than Jones seems to have suggested.

This article was originally published in 2009. David Schultz is a professor in the Hamline University Departments of Political Science and Legal Studies, and a visiting professor of law at the University of Minnesota. He is a three-time Fulbright scholar and author/editor of more than 35 books and 200 articles, including several encyclopedias on the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court, and money, politics, and the First Amendment.