In Brown v. Socialist Workers ’74 Campaign Committee, 459 U.S. 87 (1982), the Supreme Court ruled that the First Amendment right of association prohibits states from compelling minor political parties to disclose the names of contributors and recipients of disbursements when there is a reasonable probability that those persons will be subject to threats, harassment, or reprisals.

Ohio required candidates to disclose information of contributors

In 1974 the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) challenged an Ohio law requiring candidates for political office to disclose the names and addresses of those who had contributed to and received payments from their campaigns. The SWP argued that the disclosure requirements violated its First Amendment rights to privacy of association and belief. In 1981 the district court, citing Buckley v. Valeo (1976), agreed.

Forced disclosure serves a ‘compelling’ government interest for major political parties but not minor ones

According to the precedent established in Buckley, the First Amendment prohibits government-forced disclosure of political associations and beliefs, unless there is a “subordinating interest of the state [that is] compelling.” For major political parties, requiring disclosure of contributions serves the government’s interest in enhancing voters’ knowledge about candidates’ alliances, deterring corruption, and enforcing contribution limits.

For minor parties, however, the state’s interest in disclosure is less compelling. Such parties’ views are well publicized, and the improbability of their electoral success diminishes the chance of corrupting contributions. Therefore, minor parties are exempt from disclosure requirements when there is a reasonable probability that disclosure will subject contributors to threats and reprisals, threatening the survival of the party.

Court said compelling minor party to disclose contributors violated the First Amendment

On appeal to the Supreme Court, Ohio assistant attorney general Gary Brown argued that Buckley did not exempt minor parties from disclosing the recipients of party disbursements. According to Brown, Ohio had a compelling interest in preventing the misuse of campaign funds, and disclosure of the names of recipients imposed no burden on the SWP’s First Amendment rights. Recipients of disbursements were not likely to be subject to reprisal as receiving payment for services did not indicate support for the party.

In an opinion that was unanimous in part, Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote that compelling the SWP to disclose its contributors or recipients of disbursements violated the First Amendment.

He explained that disbursements are often wages for party workers or payments to service providers who are expressing support for an unpopular cause. Disclosure may therefore subject recipients to harassment and potentially limit the party’s ability to attract workers or purchase services.

Dissenters thought minor parties should disclose recipients of disbursements

Dissenting in part, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, joined by Justices William H. Rehnquist and John Paul Stevens, argued that compelling minor parties to disclose contributors is unconstitutional, but compelling disclosure of recipients of disbursements is not.

O’Connor noted that even minor parties may spend funds in ways that are illegal. Requiring disclosure of recipients of disbursements serves a compelling government interest in preventing illegal or corrupt campaign spending.

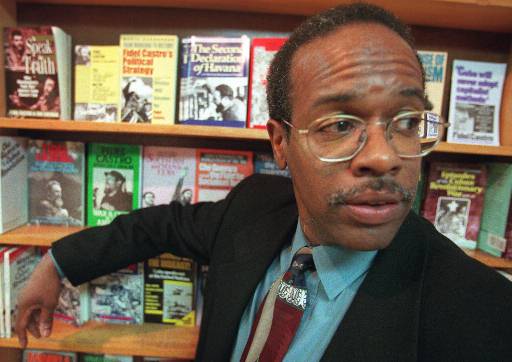

This article was originally published in 2009. Raymond B. Wrabley Jr. is a professor of political science at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. He teaches courses on American politics, policy, and political institutions that cover constitutional issues, including First Amendment controversies.