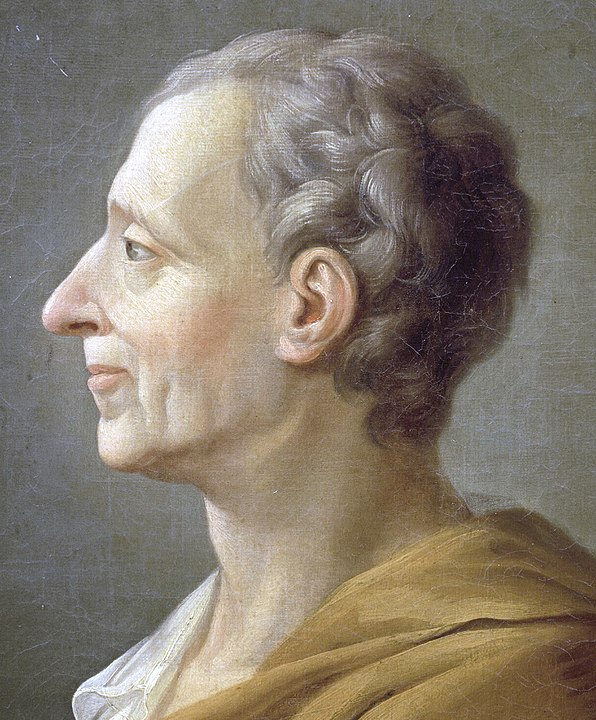

The philosophy of John Locke and other Englishmen is most associated with the American Founding and its emphasis on rights that are embodied in the Declaration of Independence, the First Amendment, and other provisions of the Bill of Rights. But one of the framers’ most quoted philosophers was Charles Louis de Secondat De Montesquieu of France, better known as the Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755), an Enlightenment thinker who was best known for his magisterial book entitled "The Spirit of the Laws" (Lutz 1984).

Montesquieu's views on separation of powers and small republics

The idea most frequently associated with Montesquieu was the idea of separation of powers, which Montesquieu appears to have borrowed in part from the theory of mixed governments formulated by the Romans.

Evoking Montesquieu, the framers of the U.S. Constitution divided the federal government into three branches (legislative, executive and judicial), to promote checks and balances and protect liberty.

Montesquieu went to great lengths in classifying governments, which he thought had to be adapted to the people over whom they governed. Montesquieu argued that governments over large land areas needed strong central leadership, which he associated with one-person rule. Anti-Federalist opponents of the new Constitution accordingly argued that a stronger central government over all 13 states would likely lead to tyranny. James Madison combatted this idea in Federalist No. 10 by distinguishing between small pure democracies, where it would be impossible for citizens collectively to assemble to govern themselves, and much larger representative democracies, where he thought that representatives embracing wider interests than those in a single city state could refine and enlarge the public views.

Montesquieu distinguished between speech and overt destructive acts

Montesquieu opposed the practice of severely punishing individuals who criticized the government or those in authority in speech or written word. In his "Spirit of the Laws," Montesquieu made a distinction that remains relevant in modern First Amendment law by distinguishing between “an overt act” against a ruler or government and a mere “idea.”

He thus wrote in Book 12, Chapter 12 that:

Overt acts do not happen every day; they are exposed to the eye of the public; and a false charge with regard to matters of fact may be easily detected. Words carried into action assume the nature of that action. Thus a man who goes into a public market-place to incite the subject to revolt incurs the guilt of high treason, because the words are joined to the action, and partake of its nature. It is not the words that are punished, but an action in which words are employed. They do not become criminal, but when they are annexed to a criminal action: everything is confounded if words are construed into a capital crime, instead of considering them only as a mark of that crime.

Montesquieu on the value of freedom of the press

In Chapter 13 of this same book, Montesquieu mounted a similar defense of freedom of the press. After noting that censorship had led to the demise of “Roman liberty,” he thus observed that while “satirical writings” were “hardly known in despotic governments, “In democracies they are not hindered, for the very same reasons which causes them to be prohibited in monarchies; being generally levelled against men of power and authority, they flatter the malignancy of the people, who are the governing party.”

Montesquieu on religious freedom

Montesquieu, who believed that religious beliefs and fear of eternal rewards or punishment, could lead to better civic life, also favored religious toleration, such as that later reflected in the free exercise clause of the First Amendment. His distinction between religious beliefs and actions would undoubtedly have permitted restrictions of religious practices that harmed others.

John R. Vile is dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University and a history professor.