Scholars have long been interested in Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and his development of the clear and present danger test in Schenck v. United States (1919). It was one of the Supreme Court’s first and most important decisions in this area, upholding the Espionage Act conviction of individuals who had discouraged potential World War I draftees from serving.

Later in 1919, Holmes authored the Supreme Court decision in Debs v. United States (1919) sustaining Debs’ conviction under the Sedition Act of 1918 but dissented in the case of Abrams v. United States, in which immigrants had distributed leaflets against U.S. military intervention in Russia. In Abrams, Holmes did not believe the individuals charged had presented the kind of clear and present danger that he had described.

It is now known, however, that Holmes had written a dissent in a case that preceded both of these, namely, Baltzer v. United States, but that was not published until many years after.

German immigrants were convicted under Espionage Act in Baltzer case

This case arose in South Dakota when German immigrants, some of whom were socialists, drafted a petition to the governor complaining about the way that quotas for draftees were being apportioned among counties, rejecting the idea that the government should go into debt to pay for the war, and threatening to vote against him. They were indicted under the Espionage Act for interfering with military recruiting and were convicted, fined, and sent to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. Attorney Joe Kirby, the son of Irish immigrants, took their case to the U.S. Supreme Court where he relied on First Amendment freedoms of speech, petition and assembly.

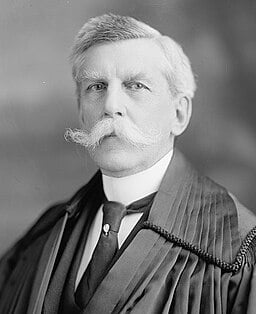

After the Supreme Court heard the case and voted 7-2 to uphold the convictions, Justice Holmes wrote a dissenting opinion, which he circulated, and which Justice Louis Brandeis was set to join. Seeking unanimity and fearing the impact of such a dissent, Chief Justice Edward Douglass White delayed the opinion, and the federal government confessed to procedural errors and sent the case back to South Dakota courts where the case was dropped as indefensible. Holmes’ dissent was not published until decades later.

Holmes’ unpublished dissent upheld First Amendment freedoms

Noting that the only evidence against the defendants was contained in a petition to the governor that was not publicly circulated, Holmes observed that the governor was not even responsible for the policies to which the petitioners were objecting. He observed that “the petition was “nothing in the world but the foolish exercise of a right” and that he could not “see how asking a change in the mode of administering the draft so as to make it accord with what is supposed to be required by law can be said to obstruct it.” He further wrote, “From beginning to end the changes advocated are changes by law, not in resistance to it, the only threat being that which every citizen may utter, that if his wishes are not followed his vote will be lost.”

Distinguishing this petition form “real obstructions to the law” that gave “real aid and comfort to the enemy,” Holmes cautioned about allowing hopes for wartime success to “hurry us into intolerance of opinions and speech that could not be imagined to do harm, although opposed to our own.”

“It is better for those who have unquestioned and almost unlimited power in their hands to err on the side of freedom,” he wrote. Acknowledging that individuals could sometimes be punished for speech after they had uttered or published it, he believed that “the emergency would have to be very great before I could be persuaded that an appeal for political action through legal channels, addressed to those supposed to have power to take such action was an act that the Constitution did not protect as well after as before.”

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.