Congress enacted the Espionage Act of 1917 on June 15, two months after the United States entered World War I. Just after the war, prosecutions under the act led to landmark First Amendment precedents.

Espionage Act limited dissent to the war

The Espionage Act of 1917 prohibited obtaining information, recording pictures, or copying descriptions of any information relating to the national defense with intent or reason to believe that the information may be used for the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation.

The act also created criminal penalties for anyone obstructing enlistment in the armed forces or causing insubordination or disloyalty in military or naval forces.

Further, the Wilson administration determined that any written materials violating the act or otherwise “urging treason” were “nonmailable matter,” and Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson ordered local postmasters to report any suspicious materials. Along with Attorney General Thomas Watt Gregory, Burleson led the way in aggressively enforcing the Espionage Act of 1917 to limit dissent.

By 1918, in actions that seriously threatened First Amendment freedoms and that likely would not be upheld today, 74 newspapers had been denied mailing privileges.

Daniel Ellsberg, pictured here, was a former defense analyst who leaked the famous Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and other newspapers. Ellsberg faced charges under the Espionage Act, and went to trial in Los Angeles in 1973. The judge eventually dismissed charges against him and his colleague Anthony Russo. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court rules wartime danger justifies restrictions

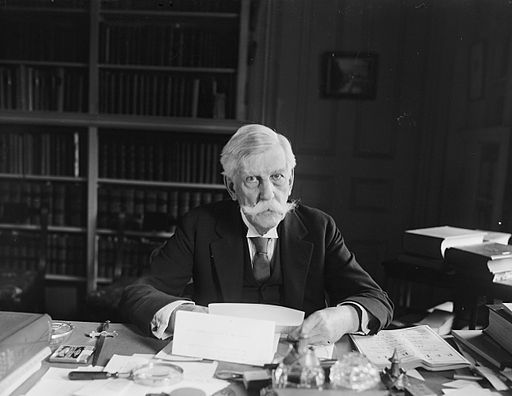

In 1917 the socialist Charles T. Schenck was charged with violating the Espionage Act after circulating a flyer opposing the draft. In Schenck v. United States (1919), the Supreme Court upheld the act’s constitutionality. Writing for the majority, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. held that the danger posed during wartime justified the act’s restriction on First Amendment rights to freedom of speech.

In June 1918, Title 1 of the Espionage Act was expanded to limit speech critical of the war with the passage of the Sedition Act of 1918. This new law led to similar convictions that were ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court in Debs v. United States (1919), Frohwerk v. United States (1919), and Abrams v. United States (1919).

Although Congress repealed the Sedition Act of 1918 in 1921, many portions of the Espionage Act of 1917 are still law.

Daniel Ellsberg, a former defense analyst who leaked the famous Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and other newspapers, faced charges under the Espionage Act, and went to trial in Los Angeles in 1973. The judge eventually dismissed charges against him and his colleague Anthony Russo.

U.S. has prosecuted leakers, publishers under Espionage Act

The United States has continued to prosecute individuals under the Espionage Act.

While most prosecutions have involved the leakers of classified documents, the government obtained a guilty plea in June 2024 from WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange for "conspiracy to obtain and disclose national defense information,"violating the Espionage Act.

Assange began published leaked documents in 2010 about the U.S. war in Afghanistan and Iraq. Some of the documents reflected poorly on the United States. Other documents exposed a U.S. spying program against European Union leaders and still others revealed the identity of people in those countries who were giving information to the United States. He was indicted in May 2019 in Virginia.

Press freedom advocates have worried about the charge related to publication of classified documents, outside of the efforts to obtain them, arguing that this could create a chilling effect on journalists who cover national security.

Other Espionage Act charges were filed against former CIA analyst Edward Snowden who leaked classified documents related to the National Security Agency’s widespread surveillance program in 2013, beginning with The Guardian. Many news outlets published the information from the documents, including the New York Times, Washington Post and NBC News. Snowden sought asylum in Russia, but could be prosecuted under the charges if he returned to the United States.

Some have called on repeal or changes to the Espionage Act. In 2022, for example, a new wave of criticism emerged after federal agents searched former president Donald Trump’s residence in Florida for top secret government documents that may have been taken when he left office. The search warrant referred to the Espionage Act as a possible law that had been broken.