William O. Douglas (1898–1980), the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court, sat on the Court from 1939 to 1975. He was one of the Court’s most controversial members as well as one of its most passionate defenders of individual freedoms and First Amendment rights.

Douglas was born on October 16, 1898, in Maine, Minnesota, but his family moved to the West Coast when he was very young. After his father’s death in 1904, the family settled in Yakima, Washington. Douglas was valedictorian of his high school class, earning a scholarship to attend Whitman College. After graduation, he made a brief attempt at teaching before attending Columbia University Law School, from which he graduated in 1925.

Finding that a career as a practicing lawyer did not suit him, Douglas joined the faculty at Columbia and then at Yale Law School, where he taught commercial law. In 1936 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him to the new Securities and Exchange Commission; he became its chair in 1937.

Douglas aspired to the Presidency

On March 20, 1939, Roosevelt nominated Douglas to the Supreme Court as an associate justice to replace Justice Louis D. Brandeis, who had retired. The Senate confirmed the appointment by a 62-4 vote, and the 40-year-old Douglas was sworn in on April 17, 1939, becoming one of the youngest justices to join the Court. By his own admission, however, he was unhappy on the bench. Although he served as a justice for thirty-six years, he aspired to the Presidency. He sought the Democratic nomination for the vice-presidency in 1944 and was bitter when Senator Harry S. Truman was chosen instead (and then became President upon Roosevelt’s death in 1945). Another brief, failed attempt in 1948 marked the end of his Presidential dreams.

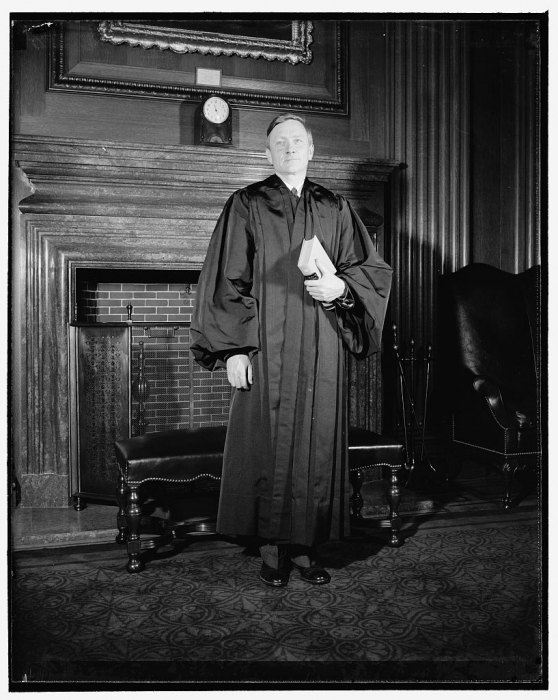

Justice William O. Douglas in 1946. Douglas’s tenure on the Court proved to be as controversial as it was long. A maverick professionally and personally, he was nicknamed “Wild Bill.” As a justice, Douglas was an unusually visible figure whose passionate advocacy made him a lightning rod for criticism. He made numerous public appearances and wrote many books and articles supporting liberal causes, especially civil liberties. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Douglas was a controversial justice

Douglas’s tenure on the Court proved to be as controversial as it was long. A maverick professionally and personally, he was nicknamed “Wild Bill.” As a justice, Douglas was an unusually visible figure whose passionate advocacy made him a lightning rod for criticism. He made numerous public appearances and wrote many books and articles supporting liberal causes, especially civil liberties. An avid outdoorsman, he worked tirelessly for the environmental movement.

He drew criticism when he blocked the pending execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in 1953 for giving atomic and military secrets to the Soviet Union and, later, when he upheld a lower court order that would have blocked funding for the Vietnam War. In each case, he issued his order and promptly left Washington, forcing the other justices to over-rule him in absentia. The House of Representatives made three short-lived attempts to impeach him.

Douglas’s personal life also was equally controversial. He married four times (progressively younger women) and divorced three of his wives. While quiet affairs were not unknown among justices, Douglas’s womanizing was common knowledge. He also had a tendency to exaggerate.

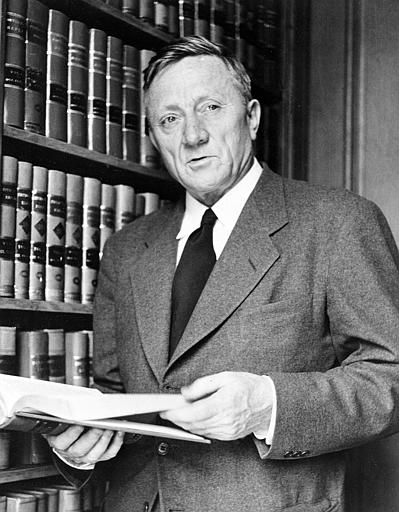

Justice William O. Douglas in 1952. As a justice, Douglas was a passionate civil libertarian. He believed that the Constitution rests upon fundamental and transcendent natural rights that limit government. Douglas was uncompromising in his support of free speech rights. He repeatedly contended that thought and speech may not be limited in the absence of injurious actions. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Douglas was a passionate supporter of free speech

As a justice, Douglas was a passionate civil libertarian. He believed that the Constitution rests upon fundamental and transcendent natural rights that limit government. Although he never seriously developed this theory, it is evident in his authorship of the Court’s decisions in Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942) and Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), both of which establish basic rights — to marriage, procreation, and privacy — not found in a literal reading of the Constitution.

Douglas was uncompromising in his support of free speech rights. While never completely endorsing the absolutist doctrine advocated by Justice Hugo L. Black, Douglas repeatedly contended that thought and speech may not be limited in the absence of injurious actions. Douglas wrote the majority opinion in Terminiello v. Chicago (1949), overturning the disorderly conduct conviction of an anti-Semitic priest whose stirring speech nearly led to a riot. Similarly, Douglas rejected the idea that obscenity should be unprotected speech in his dissent in Roth v. United States (1957). In his dissent in Dennis v. United States (1951), Douglas argued that mere membership in a group such as the Communist Party does not pose a clear and present danger that warrants banning speech and limiting association.

He stressed the importance of free speech to the United States: “Free speech has occupied an exalted position because of the high service it has given our society. Its protection is essential to the very existence of a democracy. . . . It has been the safeguard of every religious, political, philosophical, economic, and racial group amongst us. . . . [Free speech] has been the one single outstanding tenet that has made our institutions the symbol of freedom and equality.”

Douglas believed the government needed a compelling interest for any limit on speech or press

Along the same lines, Douglas joined the majority in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) and New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), insisting that the government must have a compelling and immediate interest to impose any limit on speech or the press. Writing for the majority in Murdock v. Pennsylvania (1943), Douglas struck down a local license tax required for door-to-door solicitation because it applied to Jehovah’s Witnesses and amounted to a tax on religious speech. Douglas’s concurrence in Engel v. Vitale (1962), the landmark school prayer case, reflected a wider wariness about using any tax funds for religious purposes.

In his decision allowing “released time” for public school children to attend off-campus religious instruction in Zorach v. Clauson (1952), however, Douglas observed that “we are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.” Accommodation of such religious beliefs “follows the best of our traditions” and “respects the religious nature of our people.”

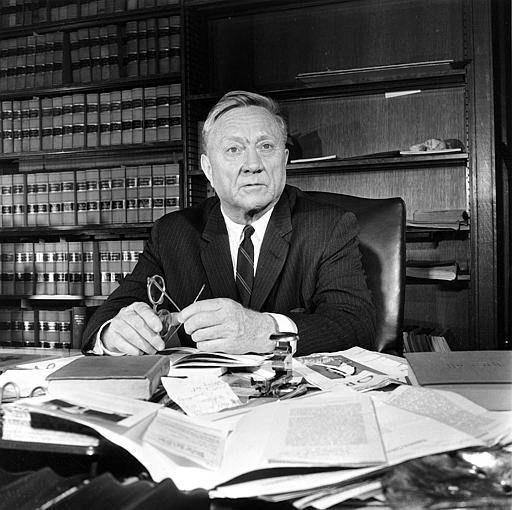

Justice William O. Douglas in 1963. Douglas insisted that the government must have a compelling and immediate interest to impose any limit on speech or the press. Douglas rejected the idea that obscenity should be unprotected speech in his dissent in Roth v. United States (1957) and argued that mere membership in a group such as the Communist Party does not pose a clear and present danger that warrants banning speech and limiting association. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Douglas became “The Great Dissenter”

Douglas’s defense of civil liberties put him in step with the Warren Court but made him increasingly at odds with the Burger Court that followed. As the Court became more conservative, Douglas wrote increasing numbers of dissents, leading to another nickname: “The Great Dissenter.” Liberal and conservative commentators alike have criticized Douglas for failing to live up to his brilliant potential as a jurist. As noted, he never made an effort to develop the natural law theory he endorsed. Further, Douglas wrote many of his opinions in as few as thirty minutes and rarely revised them, leading to sloppy legal scholarship and thus diminishing their impact.

On December 31, 1974, Douglas suffered a debilitating stroke but did not retire until November 12, 1975. He attempted to fulfill his duties on the Court until his disability became so obvious that his fellow justices agreed among themselves to put off any cases in which he would have the deciding vote.

This article was originally published in 2009. Stephen Robertson is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Middle Tennessee State University, where he has taught for about 25 years. He has always had a deep interest in constitutional law and the First Amendment and explores these topics in his courses on American government and women’s rights under American law.