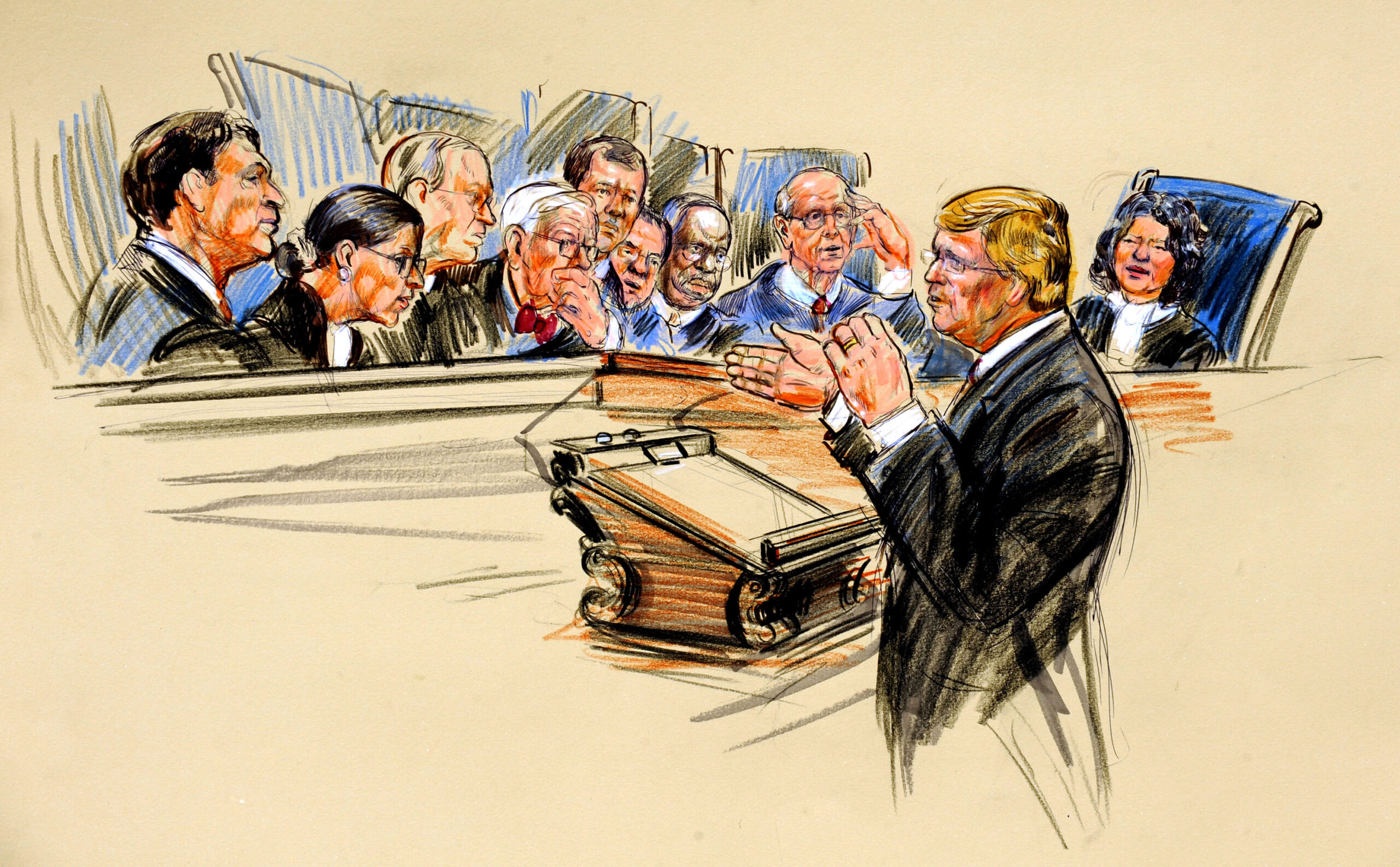

In Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, a sharply divided (5-4) U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a provision of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) that prohibited corporations and unions from using their general treasury funds for express advocacy or electioneering communications.

This decision is one of the most talked about and controversial First Amendment decisions issued by the U.S. Supreme Court in recent memory.

Citizens United wanted to release an electioneering film

Citizens United, a nonprofit corporation, released a film titled Hillary: The Movie in January 2008.

The film was highly critical of Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. Citizens United wanted to make the movie available on video-on-demand. They also wanted to promote the video-on-demand by running ads on broadcast and cable television.

However, a key provision of the BCRA – 2 U.S.C. §441b – that prohibited corporations or unions from using their general treasury funds to make independent expenditures (spending) for “electioneering communications” – defined as speech expressly advocating the election or defeat of a political candidate that is made within 30 days of a primary or 60 days within a general election.

Citizens United challenged the constitutionality of this provision of the BCRA, as well the law’s disclaimer and disclosure requirements. The district court denied Citizens United’s motion for a preliminary injunction, upholding the challenged provisions of the BCRA. On appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed in part and reversed in part.

Restricting political speech requires strict scrutiny

Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy struck down the ban on corporations and unions from using their general treasury funds for electioneering communications but upheld the disclaimer and disclosure requirements.

Addressing the electioneering ban, Kennedy noted that the restriction regulated political speech, the type of speech that should be most protected by the First Amendment. He noted that as a content-based restriction on political speech, the restriction must be evaluated under strict scrutiny.

Kennedy also rejected the idea that speech rights should be limited because they are being advanced by corporations.

“We find no basis for the proposition that, in the context of political speech, the Government may impose restrictions on certain disfavored speakers,” he wrote, adding that “the First Amendment does not allow political speech restrictions based on a speaker’s corporate identity.”

Kennedy’s analysis supported the holding in First National Bank of Boston v. Bellotti (1978) and overruled Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990).

Kennedy invoked counterspeech doctrine and prior restraint

The government argued that the ban served its compelling interest in fighting corruption. But, Kennedy responded that “the anticorruption interest is not sufficient to displace the speech here in question.”

He added that the traditional First Amendment rule is more speech, not less. In his opinion, Kennedy invoked time-honored First Amendment concepts, such as the counterspeech doctrine and prior restraint.

Regarding the disclaimer and disclosure requirements, Kennedy determined those to be constitutional on their face. He noted that disclaimer and “disclosure is a less restrictive alternative to more comprehensive regulations of speech.”

Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. authored a concurring opinion, joined by Justice Samuel Alito. He emphasized that “the test and purpose of the First Amendment point in the same direction: Congress may not prohibit political speech, even if the speaker is a corporation or a union.” He also wrote about the importance of stare decisis but agreed that the Court should overrule Austin.

Justice Antonin Scalia also wrote a concurring opinion. He explained that the text of the First Amendment countenanced against excluding corporations from the protections of the First Amendment. “Its text offers no foothold for excluding any category of speaker,” he wrote.

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. Thomas, the Court’s most forceful defender of the First Amendment against campaign finance regulation, would have invalidated not only the electioneering provision but also the disclosure and disclaimer requirements.

Dissenters wrote that ruling greatly increases the power of corporations in elections

Justice John Paul Stevens dissented, joined by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor. He called the majority decision “profoundly misguided” and wrote that the “ruling threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the Nation.”

He wrote that the majority ruling greatly increases the power and influence of corporations in determining the winner of elections.

History shows, according to Stevens, that corporations are subject to extensive regulation. Over the past century, Congress has regulated corporations in elections to preserve the integrity of elections. He accused the majority of taking a very “crabbed” view of corruption and fostering the “denial of Congress’ authority to regulate corporate spending on elections.”

Numerous proposals to amend the Constitution to overrule the Court’s decision in Citizens United have been advanced. President Barack Obama publicly criticized the Court’s ruling.

Justice Stevens, in retirement, advocated for a constitutional amendment to overrule the decision.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2017.