In Young v. American Mini Theatres, 427 U.S. 50 (1976), the Supreme Court upheld the zoning of adult businesses in Detroit. This case marked the first judicial recognition of zoning laws, which can be used to zone adult businesses based on their harmful secondary effects (secondary effects doctrine).

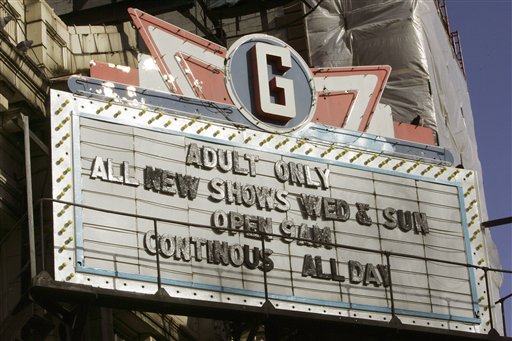

The operators of two adult motion picture theaters — the Nortown and the Pussy Cat — challenged amendments to Detroit’s Anti-Skid Row ordinance. The ordinance prohibited adult businesses from locating within 1,000 feet of any two other such “regulated uses” and 500 feet from a residential area. The two theatre operators contended that the ordinance violated the First Amendment because it singled out adult businesses on the basis of the content of the films shown.

A federal district court ruled in favor of the city, but the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed and found the Detroit ordinance unconstitutional. On appeal, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 to uphold the zoning law.

Supreme Court upholds zoning laws aimed at secondary effects of adult businesses

Writing for the majority, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that the ordinance was not too vague. He noted that the sexual expression at issue was not entitled to as much protection as political speech. “Even within the area of protected speech, a difference in content may require a different governmental response,” he wrote.

Stevens also emphasized that the city did not set out to suppress free expression. Instead, it was trying to limit the adverse effects associated with adult businesses, such as higher crime rates and lower property values. In footnote 34, he wrote: “It is this secondary effect which these zoning ordinances attempt to avoid, not the dissemination of ‘offensive’ speech.”

Dissent argues that First Amendment protects offensive expression

Justices Potter Stewart and Harry A. Blackmun wrote dissenting opinions. Calling the majority decision an “aberration,” Stewart criticized the majority for “rid[ing] roughshod over cardinal principles of First Amendment law,” such as the presumption against content-based laws and the First Amendment’s protection of offensive expression. In his dissent, Blackmun reasoned that the law was unconstitutionally vague because theatre owners would have to guess at what types of films the city was classifying as adult.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.