After the Supreme Court’s decision in Dennis v. United States (1951), two questions — one of fact and one of theory — dominated the First Amendment legal landscape: Would the U.S. government continue to prosecute American communists successfully? Would the clear and present danger test survive as the leading First Amendment standard in cases involving advocacy of illegal conduct?

Although the Court answered the first question in Yates v. United States, 354 U.S. 298 (1957), its failure to address the second inquiry contributed to the demise of the clear and present danger test more than a decade later in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969).

Yates virtually terminated prosecutions of American Communists

The Court’s decision in Dennis, which upheld the convictions of leading American communists under the Smith Act of 1940 for organizing a party to overthrow the government, prompted the Justice Department to proceed with 15 new prosecutions of 129 communists in the United States; 96 of these were convicted, while only 10 were acquitted. The Court’s decision in Yates virtually terminated these prosecutions. Only one additional prosecution and conviction was obtained after 1957, under the membership provisions of the Smith Act, in Scales v. United States (1961).

Court raised the bar on Smith Act convictions, protected advocacy of ideas

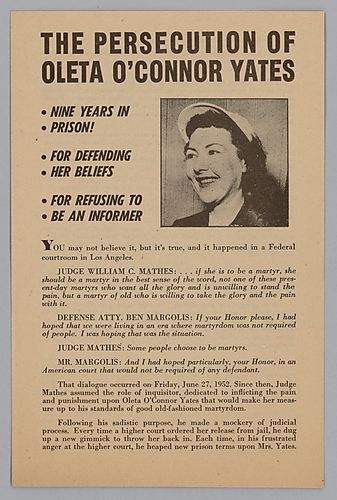

In circumstances strikingly similar to Dennis, Oleta Yates and 13 codefendants — members of the second tier of leadership in the Communist Party of the United States — participated in and spoke at party meetings, advocating the forcible overthrow of the U.S. government. They were charged and convicted in federal court of conspiracy to violate the Smith Act. Their appeals hinged upon two issues: the extent to which the Court’s prior decision in Dennis applied to abstract advocacy of ideas versus incitement to overthrow the government, and whether the evidence presented was sufficient to justify conviction for criminal conduct. The Court voted 6-1 to remand the case to the district court with orders to dismiss the case against five defendants and to consider retrial for the other nine.

The decision in Yates produced a firestorm of criticism, including from President Dwight Eisenhower and FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover who believed it hurt their efforts to rout out the Communist Party in Ameria. In this photo, Eisenhower, center, meets with Attorney General Herbert Brownell, left, and Hoover at the Summer White House in Denver, Colorado in 1954. They discussed a “substantial step-up” in the drive to “utterly destroy” the Communist Party in the U.S. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Justice John Marshall Harlan II, writing for the majority, answered the “advocacy of doctrine” versus “advocacy of action” question so as to raise the bar for convictions under the Smith Act. Harlan’s opinion required that prosecutors in Smith Act cases must prove that the accused advocated illegal conduct, not mere abstract doctrine. Because the government could not meet this burden, the charges against all defendants in Yates were dismissed.

Court abandoned clear and present danger test for First Amendment cases

Although Yates addressed issues relevant to the line between abstract advocacy of political doctrine and incitement to unlawful action, all of the opinions avoided mention of the clear and present danger test. The Court wrote as if the test had vanished from the First Amendment lexicon. In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), which overturned the conviction of a Ku Klux Klan leader for his remarks, the Court formally abandoned the test for adjudicating incitement cases.

The Yates decision produced a firestorm of criticism. Members of Congress introduced several bills to curtail the Court’s jurisdiction in cases involving allegations of subversive activities. Although Congress did not enact any of these into laws, some justices seemed to respond to congressional pressure in subsequent cases, until the search for domestic communists slackened in the 1960s.

This article was originally published in 2009. Richard A. “Tony” Parker is an Emeritus Professor of Speech Communication at Northern Arizona University. He is the editor of Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives On Landmark Supreme Court Decisions which received the Franklyn S. Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression from the National Communication Association in 1994.