In Ward v. Rock against Racism, 491 U.S. 781 (1989), the Supreme Court ruled that New York City officials could control the volume of amplified music at rock concerts in Central Park without violating the First Amendment.

The decision clarified that time, place, and manner regulations on speech do not have to limit speech in the least restrictive way possible.

City adopted regulations after complaints of excessive noise

In an effort to control the volume at Naumberg Acoustic Bandshell, an amphitheater in Central Park, the city of New York adopted a regulation that required performers at concerts to use sound amplification equipment and a sound technician provided by the city. The city passed the regulation after repeated complaints of excessive noise by nearby residents and other users of the park.

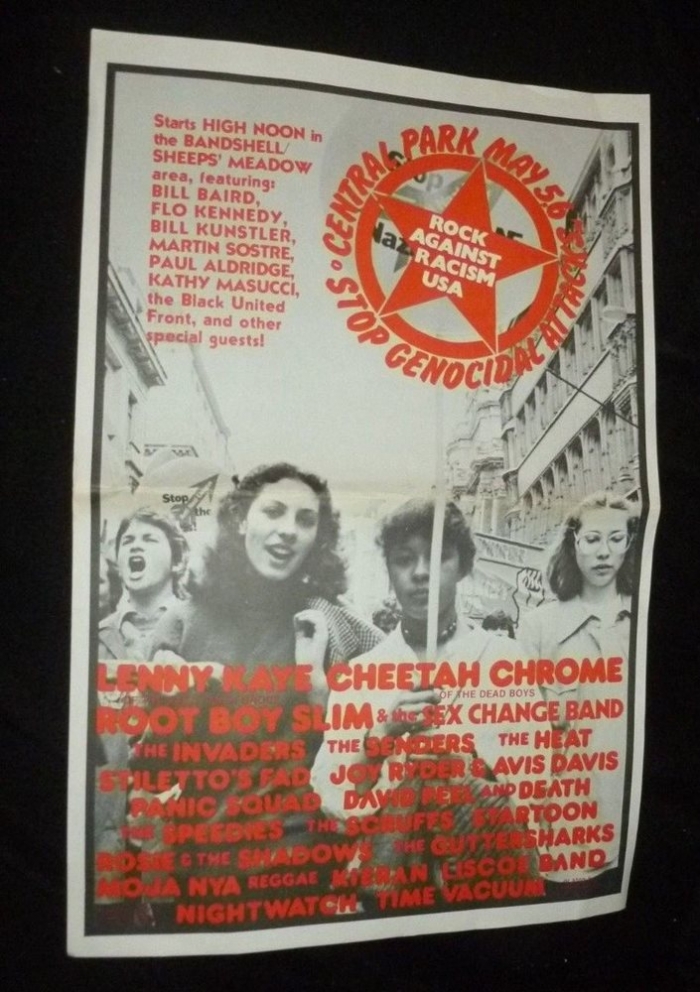

Rock against Racism, a group that regularly performed rock concerts at the shell, challenged the regulation, contending that it constituted an impermissible content-based restriction on speech. The group, which in the past had provided its own sound technician at concerts, also contended that the city could control noise in less speech-restrictive ways than forcing performers to use a city sound technician.

Court upheld regulation against First Amendment challenge

The Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of city officials. Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy recognized that music is a form of expression protected by the First Amendment. However, he emphasized that the sound amplification requirement was a time, place, and manner restriction on speech, as opposed to a content-control measure. The city’s principal purpose was not to censor content but merely to control noise levels. Kennedy clarified that a time, place, and manner regulation “must be narrowly tailored to serve the government’s legitimate, content-neutral interests but that it need not be the least restrictive or least intrusive means of doing so.” Justice Thurgood Marshall — joined by Justices William J. Brennan Jr. and John Paul Stevens— wrote a dissenting opinion, arguing that the majority had “abandoned the requirement that restrictions on speech be narrowly tailored in any ordinary use of phrase.” He also found that the city’s guidelines “constitute a quintessential, and unconstitutional, prior restraint.” David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.

The Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of city officials. Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy recognized that music is a form of expression protected by the First Amendment. However, he emphasized that the sound amplification requirement was a time, place, and manner restriction on speech, as opposed to a content-control measure.

The city’s principal purpose was not to censor content but merely to control noise levels. Kennedy clarified that a time, place, and manner regulation “must be narrowly tailored to serve the government’s legitimate, content-neutral interests but that it need not be the least restrictive or least intrusive means of doing so.”

Justice Thurgood Marshall — joined by Justices William J. Brennan Jr. and John Paul Stevens— wrote a dissenting opinion, arguing that the majority had “abandoned the requirement that restrictions on speech be narrowly tailored in any ordinary use of phrase.” He also found that the city’s guidelines “constitute a quintessential, and unconstitutional, prior restraint.”

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.