Although many Americans likely take the First Amendment’s establishment clause for granted, King Henry VIII and his successors became the head of the Anglican Church after splitting from the Roman Catholic church and renouncing the authority of the pope. Moreover, many of the early colonies in America had established churches, and even liberal thinkers such as John Locke permitted restrictions on Roman Catholics and atheists.

In early America, Roger Williams broke away from the Massachusetts Bay Colony to found Rhode Island as a sanctuary for those who did not want state support for the established congregational church. Baptists such as John Leland and Isaac Backus later opposed state establishments and, along with Thomas Jefferson, pushed James Madison and others for the adoption of the First Amendment and other provisions within the Bill of Rights.

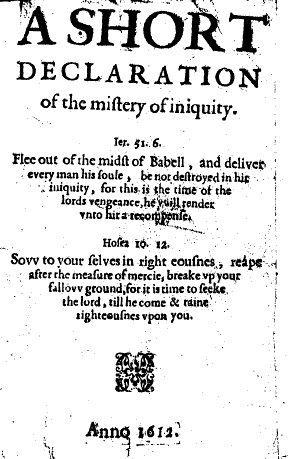

Early Baptist leader Helwys defended religious liberty

Thomas Helwys (ca. 1550-ca. 1616) was an English Baptist minister who lived during a time of great political turmoil and religious persecution and likely died in prison as a result of his advocacy of freedom of conscience.

In 1612, just one year after the publication of the King James Version of the Bible in English, Helwys authored “A Short Declaration of the Mystery of Iniquity” in which he defended such basic Baptist doctrines as believer’s baptism by immersion (excluding child baptism), congregational authority to call and dismiss their own ministers, and the right of individuals to interpret scriptures for themselves.

This was predicated on the argument that kings and other governmental officials did not have the authority over human consciences. Although John Smyth is credited with founding the first Baptist congregation (in Holland), Helwys founded the first such church in England (Groves, 1998, xxiv).

Helwys constantly quotes from the Bible, and his prose is fairly dense, but it signaled the establishment of a denomination that continues to argue for separation of church and state in England, the United States, and elsewhere and that grew especially rapidly in the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries.

Helwys told King James he had no religious power over his subjects

Helwys thought that both the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England had been prophesied as two beasts in the biblical book of Revelation, which improperly attempted to control the people’s beliefs through their bishops. He further quarreled with Puritans who sought to purify the latter church, including those who fled to and remained in Holland rather than returning, as he had done, to face persecution and spread the gospel in England.

Helwys argued for full freedom of conscience, believing that religious beliefs were not the proper subject of civil government. A note that he wrote inside the cover of his book that was sent to King James may have led to his incarceration and eventual death. It reminded the king that “The king is a mortal man and not God, therefore has no power over the immortal souls of his subjects, to make laws and ordinances for them, and to set spiritual lords over them. If the king has authority to make spiritual lords and laws, then he is an immortal God and not a mortal man” (Groves 1998, xxiv).

Helwys did not think faith, prayer could be compelled by government

Helwys divided his volume into four books and an appendix. His primary defense of religious freedom was found in book two.

Helwys believed that the only government in which God had been king was ancient Israel, and he believed that only Jesus had inherited the right as the heir to the throne of David to kingship over spiritual matters. Helwys did believe that the Bible taught respect for kings and others in authority, but only insofar as they confined themselves to nonspiritual matters, which each person had to determine individually.

He did not think it was any more valid for a Protestant king to determine the religious faith and practice of his subject than it was for a Catholic king to do so. He did not believe that faith could be compelled through physical force. As he noted “It is spiritual obedience that the Lord requires, and the king’s sword cannot smite the spirits of men. And if our lord the king shall force and compel men to worship and eat the Lord’s Supper against their consciences, so shall he make his poor subjects to worship and eat unworthily, whereby he shall compel them to sin against God, and increase their own judgements” (1998, 37).

Helwys called upon the king to allow “that blessed liberty to read and hear the Word of God in their own language and to pray in their public worship in their own tongue, that so by our lord the king’s means the king’s people may enjoy his blessed liberty to understand the scriptures with their own understanding and pray in their public worship with their won spirits” (1998, 44). He observed that “Then if men err, their sin shall be upon their own heads, and the kings’ head shall be innocent and clear from their transgression, which it cannot be if the king shall willingly suffer his power to be used to compel men to pray and understand by the direction of the lord bishops’ spirit” (1998, 44).

Hewlys’ book was first exposition in English of religious liberty

In contrast to those who favored freedom only for Catholics or Protestants, Helwys willingly extended it to all: “For men’s religion to God is between God and themselves. The king shall not answer for it. Neither may the king be judge between God and man. Let them be heretics, Turks, Jews, or whatsoever it appertains not to the earthly power to punish them in the least measure” (1998, 53).

Although Hewlys’ book is not thought to have had much influence on his contemporaries, it remains a testament to the development of liberalizing ideas of religious freedom. Church historians have concluded that the book “must be granted a place in history on the grounds that it contains the first exposition in English of the notion of freedom conscience or religious liberty. When toleration was the liberal idea of the day, Helwys called for “universal religious liberty—for freedom of conscience for all’” (Groves 1998, xxxi-xxxii).

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.