The Illinois Supreme Court decision in Spies v. Illinois, 122 Ill. 1; 12 N.E. 865 (1887), affirmed the convictions of individuals involved in the notorious Haymarket Riot of May 1886. The jury relied in part on prior statements that the accused had made.

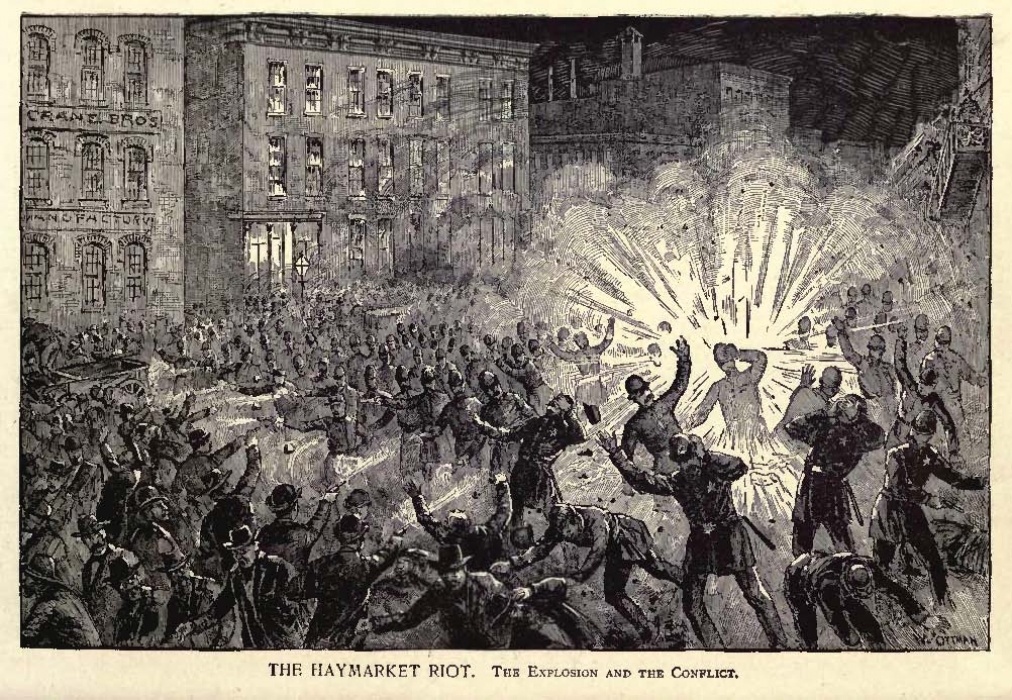

Workmen had gathered at Haymarket Square in Chicago to agitate for an eight-hour workday. During the event, which began peacefully, police asked the demonstrators to disperse. Someone from the crowd threw a bomb into a group of police officers. Gunfire ensued. Numerous officers and demonstrators were killed.

Haymarket Riot led to death sentences for socialists, anarchists based partly on their speech

Eight anarchists and socialists were indicted for the incident and all but one sentenced to death. Illinois Governor Richard Oglesby eventually granted clemency to two individuals, one committed suicide, and the other four were executed.

Scholars generally agree that the judge and jury were strongly prejudiced against the defendants during the flawed trial. Paul Avrich (1984:221–222) believes that this incident led to the nation’s first “Red Scare.”

He observes that it led to hundreds of arrests, the closing of two anarchist newspapers, and the imposition of near martial law for eight weeks. For a time, authorities even banned the color red from local advertising.

Illinois Supreme Court justified convictions, cited past deeds and speech

What is most interesting about this decision, written by Justice Benjamin B. Magruder, is the manner in which it attempted to establish the defendants’ guilt as “accessories before the fact” by not only focusing on their past deeds, but by also emphasizing their prior speeches and writings, some of which described bomb making and calls for workers to rebel.

Although Magruder did not specifically address the First Amendment — which the Supreme Court had yet to apply to the states — he observed that the meeting that had led to the violence “was not intended by those, who made the arrangements for holding it, to be a peaceable assemblage.” He observed that some of the flyers for the meeting specifically advised workers to come armed.

Court said inflammatory speech can incite illegal action

Magruder cited the English case of Regina v. Sharpe for the principle that “[h]e, who inflames people’s minds and induces them by violent means, to accomplish an illegal object, is himself a rioter, though he take no part in the riot.” He continued, “It was a question for the jury, whether, with the evidence before them, the attack upon the police at the Haymarket ‘was so connected with the inflammatory language used, that they can not be separated by time or other circumstances.’ ”

He did qualify this principle with the following: “We do not wish to be understood as deciding, that the influence of these publications in bringing about the crime at the Haymarket could be considered by the jury if they were the only evidence of encouragement of that crime, which was furnished by the record. We only hold, that the jury were at liberty to consider the publications in question in connection with all the other facts and circumstances of this particular case.”

Magruder argued that speech could serve as a means of “incitement” to illegal action.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.