The Sims Act, which Congress adopted in 1912 and did not repeal until 1940, limited the interstate transportation of films of professional boxing fights.

The law was drafted largely in reaction to the distribution of films of the first so-called “Fight of the Century,” which had taken place in Reno, Nevada, on July 4, 1910, and another fight on July 4, 1912.

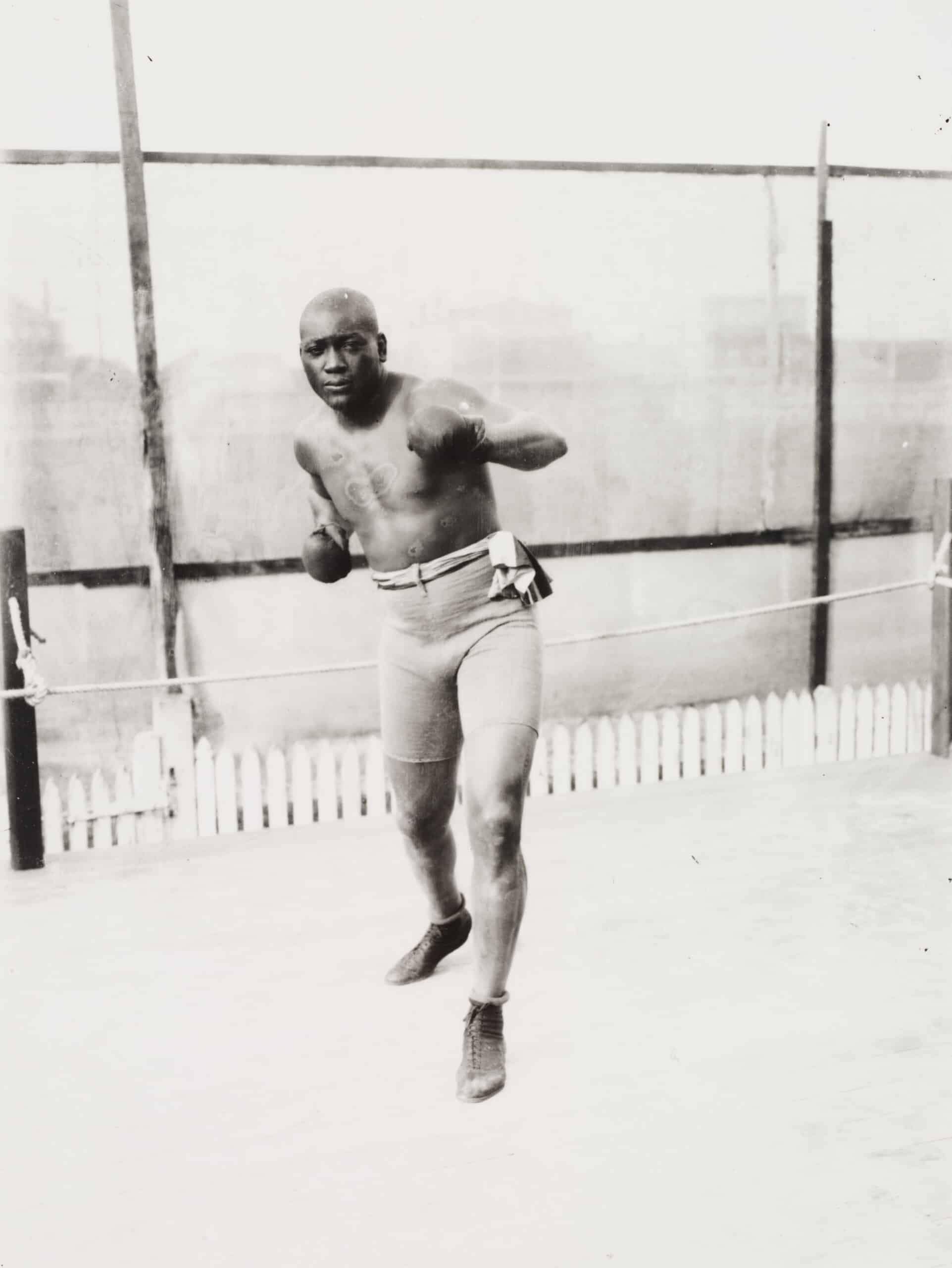

Congress limits films after wins by Black boxer

The fights were controversial because Jack Johnson, a flamboyant African American had beaten both white opponents in the matches (James J. Jeffries and Jim Flynn). Much like Jesse Owens’ later victories at the 1936 Olympics in Germany, Johnson’s wins called into question prevailing ideas of white supremacy and stirred fears of racial violence. Progressive reformers also feared that the portrayals of such violence would be a bad moral influence, especially on young people.

The law was sponsored in the U.S. House by Representatives by Thetus Sims of Tennessee and Seaborn A. Rodenberry of Georgia and in the U.S. Senate by Furniford Simmons of North Carolina and Augustus Bacon of Georgia.

Congress justified the enactment of the Sims Act under its authority to control interstate and foreign commerce, which at the time was used to control moral vices.

Even before Congress adopted the law, many states, the actions of which did not yet fall under the protection of the First Amendment, had already banned the films. Some states had also banned prize fighting altogether at a time when bare-knuckled rounds might last for 60 to 70 rounds and sometimes resulted in death (Streible 1989, 237).

NAACP not successful in getting distribution limits on KKK film

When “The Birth of a Nation,” which glorified the Ku Klux Klan and raised fears of black male violence against white women, was subsequently filmed in 1915, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) unsuccessfully pleaded for a similar ban on the film. (A performance of a play on which it had been based had stirred racial violence that included the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre.) A ban was opposed by the American Civil Liberties Union, which feared that such a ban might be a double-edged legal sword (Franks 2024, 20-21).

Supreme Court in 1952 gave First Amendment protection to films

In Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio (1915), the U.S. Supreme Court refused to extend First Amendment protections to motion pictures, in a decision that it did not reverse until 1952 in Burstyn v. Wilson.

In Weber v. Freed, 239 U.S. 325 (1915), the Supreme Court in a decision authored by Chief Justice Edward Douglass White further upheld the Sims Act as an exercise of Congress’ plenary power under the commerce clause in allowing for the confiscation of a film of a fight that Johnson had lost to Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba, in 1915.

Johnson, was later prosecuted and convicted under the Mann Act of 1910 for transporting a (white) woman across state lines for immoral purposes although he evaded his sentence by moving to Europe for a time.

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.