The concept of seditious libel arrived in North America with the first English colonists. Under English law, it was a criminal offense to publish or otherwise make statements intended to criticize or provoke dissatisfaction with the government. Truth was not a defense and, in fact, made the offense worse. English libel law applied the following maxim: “The greater the truth, the greater the libel.”

Many colonists, however, did not share this view of seditious libel. They found that the opportunities for freedom and independence in America were inconsistent with laws that smacked of tyranny. The conflict between those views came to a head in 1735 with the trial of John Peter Zenger.

Zenger trial showed the colonists’ attitude toward seditious libel

Zenger, a printer, published the New York Weekly Journal. The Journal offered New Yorkers the latest news from the colonies and England, as well as a healthy dose of criticism of New York’s appointed governor, William Cosby. In the Journal, Zenger published several articles, ballads, and false ads claiming that Cosby intended to strip New Yorkers of their rights and plunge them into slavery.

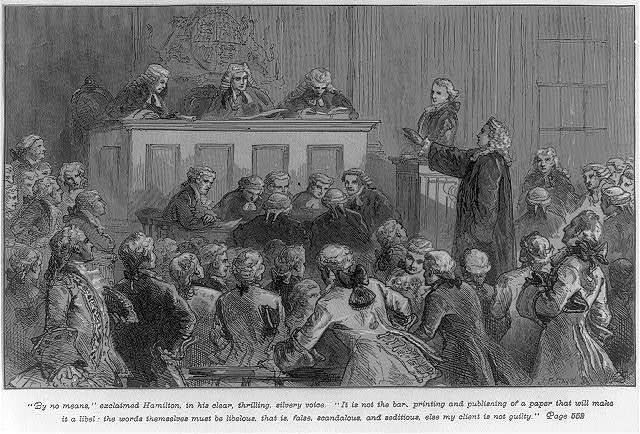

The publisher was eventually arrested and charged with seditious libel. For the trial, Cosby hand-picked two judges to determine whether the statements at issue were libelous — a conclusion they, of course, reached. The jury was then left to decide only whether Zenger had published the statements, a fact he admitted. In a surprising development, at the urging of Andrew Hamilton, one of the colonies’ foremost lawyers, the jury defied the judges and acquitted Zenger of the charge.

Congress criminalized seditious libel in 1798

Although seditious libel accompanied the English colonists, it did not leave with the English soldiers after the American Revolution. In 1798 Congress passed four laws known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. One of them, the Sedition Act, made it a crime to publish “any false, scandalous and malicious writing” about the government or its officials.

The Alien and Sedition Acts were pushed by the Federalist-controlled Congress. Federalists claimed the laws were needed to respond to the hostile actions of the French Revolutionary government, but many Americans thought the true intent was to cripple Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party. Twenty-five prominent Republicans — including several journalists and one member of Congress — were arrested and charged under the Sedition Act. Eleven of them were tried, and 10 ultimately were convicted.

The Sedition Act, as originally designed, expired when President John Adams left office in 1801. Indeed, it was the public outcry against the Alien and Sedition Acts that helped to sweep the Republicans into power. President Jefferson then pardoned those who had been convicted under the act.

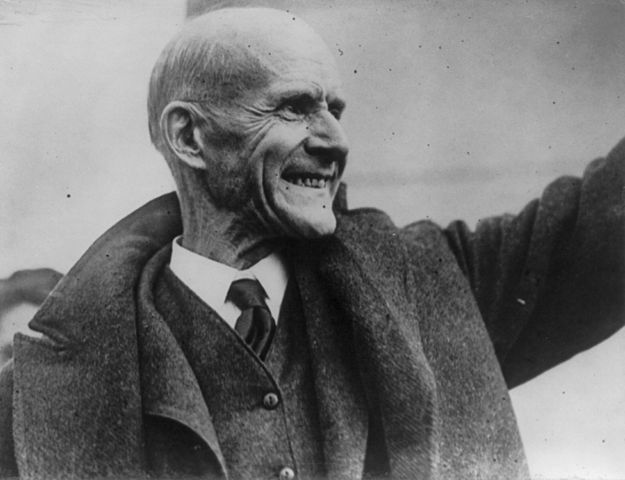

In this photo, Eugene V. Debs leaves the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta in 1921. He had been imprisoned in 1918 under the Sedition Act, a seditious libel act from World War I, for giving a speech against participation in the War. President Warren G. Harding commuted his sentence to time served in December 1921. (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

Seditious libel became an issue again in World War I

Seditious libel reared its head again during World War I. In 1917 Congress passed the Espionage Act, which it then amended in 1918 with the Sedition Act. The Sedition Act imposed “a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both” on anyone who dared “utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States.” Socialist Eugene V. Debs was sentenced to ten years in prison under the act, and many other protestors were arrested for speaking out against the war. The Sedition Act was repealed in 1921.

In 1919, however, the Supreme Court upheld a conviction under the Espionage Act. In Schenck v. United States (1919), the Court considered the arrest and conviction of a socialist who urged young men to resist the draft. In the opinion written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the Court said that First Amendment rights could be limited when “the words used are used in such a circumstance and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.”

Court later said seditious libel violated First Amendment

The Court considered seditious libel again in 1964 in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. In its seminal libel decision, the Court noted that although the Sedition Act of 1798 had not been tested in the Supreme Court, “the attack on its validity has carried the day in the court of history.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Douglas E. Lee is a circuit judge for the 15th judicial circuit in northwest Illinois. When he wrote this article, he was a partner with a law firm in Dixon, Illinois. Before joining that firm, he worked at Baker & Hostetler in Washington, D.C., where he focused his practice in First Amendment litigation. When he took the bench in 2019, Mr. Lee had considerable experience in matters involving libel, privacy, and access to the courts. He also wrote regular commentaries for the website of the First Amendment Center in Nashville.