The secondary effects doctrine permits normally unconstitutional content-based regulation to be treated as if it were content-neutral.

The doctrine took shape in the context of regulation of adult entertainment businesses, which allegedly impose adverse side effects — for example, increased crime and decreased property values — on the communities in which they are situated. In effect, the doctrine allows for a reduced degree of judicial scrutiny in the instance of regulation of adult-oriented expression. This contrasts with the strict scrutiny requirement normally accorded regulation of First Amendment–protected expression.

Critics claim that the secondary effects doctrine has proven fertile ground for abuse, enabling government officials and the communities they represent to conceal their distaste for adult entertainment behind claims of harmful effects. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. warned in his dissent in Boos v. Barry (1988) that the doctrine “could set the court on a road that will lead to the evisceration of First Amendment freedoms.”

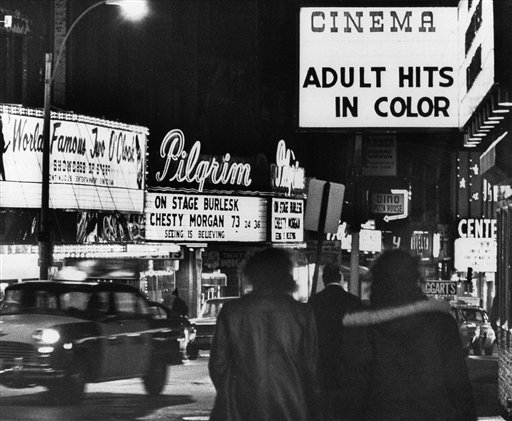

Regulations on adult entertainment businesses led to secondary effects doctrine

Adult entertainment establishments are subject to an array of zoning and licensing requirements. A typical regulation provides that adult businesses cannot be within 500 feet of a church, school, playground, or another adult-oriented business. Others dictate the distance between patrons and performers, limit the hours of operation, or prohibit totally nude dancing. Strict licensing requirements must be observed when opening adult businesses.

The Supreme Court introduced the secondary effects doctrine in its decision in Young v. American Mini Theatres (1976). The city of Detroit had adopted an anti-skid row ordinance preventing adult businesses from locating within 1,000 feet of any two existing adult businesses or within 500 feet of any residential area. The theater that challenged the law contended that the zoning ordinance was a content-based law that targeted businesses because officials did not like the expressive messages conveyed by the adult material displayed.

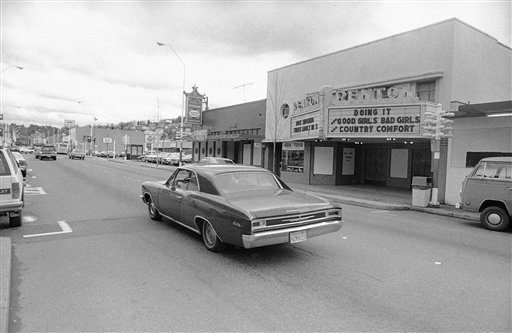

The Court expanded the secondary effects doctrine in City of Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc. (1986). The city of Renton, Washington, passed an adult-business zoning law in 1981 that prevented adult businesses, like the Renton theater pictured here, from locating within 1,000 feet of any residential area, school, park, or church. The Court upheld the ordinance based on the secondary effects rationale. (AP Photo/Barry Sweet, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court cited neighborhood deterioration as ‘secondary effect’ of adult business concentration

The Court reasoned that the law was not passed to silence offensive expression but to prevent the deterioration of neighborhoods. In a footnote, Justice John Paul Stevens characterized such neighborhood deterioration as a “secondary effect,” writing that it is “this secondary effect which these zoning ordinances attempt to avoid, not the dissemination of ‘offensive’ speech.”

The Court expanded the doctrine a decade later in City of Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc. (1986). The city of Renton, Washington, passed an adult-business zoning law in 1981 that prevented adult businesses from locating within 1,000 feet of any residential area, school, park, or church. Two adult businesses challenged the law on First Amendment grounds, pointing out that Renton officials had offered no evidence of harmful secondary effects to the city itself.

The Court upheld the ordinance based on the secondary effects rationale. In delivering the opinion of the Court, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist wrote that “our result is largely dictated by our decision in Young.”

Law targeting secondary effects of protected expression could be considered neutral

He noted that the zoning law resembled a content-based law but ruled that it could be considered content-neutral because the law targeted the secondary effects of the businesses, not their expressive content. The Court also ruled that a city does not have to conduct its own study to justify its reliance on the secondary effects argument. Instead, the city could rely on studies conducted in other cities.

The Court extended the secondary effects doctrine from land-use regulations to the content of adult expression in Barnes v. Glen Theatre, Inc. (1991).

In Barnes, a narrow majority of the Court upheld an Indiana public-nudity law applied to totally nude dancing at strip clubs.

In his concurring opinion, Justice David H. Souter relied on the secondary effects doctrine even though the restriction seemingly imposed a direct regulation on the expressive content of nude dancing.

In City of Erie v. Pap’s A.M. (2000), the Court applied the secondary effects rationale to uphold a city law banning totally nude dancing. The case involved his club, the only club in Erie, Pennsylvania, featuring all-nude dancers. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court applied secondary effects doctrine to uphold city’s ban on nude dancing

In City of Erie v. Pap’s A.M. (2000), the Court applied the secondary effects rationale to uphold a city law banning totally nude dancing.

Ironically, both Justice Stevens, who first used the term “secondary effects” in Young, and Justice Souter, who extended the secondary effects doctrine beyond zoning cases in Barnes, dissented in Pap’s A.M. Souter admitted he had made a mistake in Barnes: “I may not be less ignorant of nude dancing than I was nine years ago, but after many subsequent occasions to think further about the needs of the First Amendment, I have come to believe that a government must toe the mark more carefully than I first insisted.”

In City of Los Angeles v. Alameda Books (2002), the Court upheld a Los Angeles ordinance prohibiting a single adult establishment from functioning as both an adult bookstore and an adult arcade showing adult films. Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote that “it is rational for the city to infer that reducing the concentration of adult businesses in a neighborhood, whether within separate establishments or in one large establishment, will reduce crimes.”

Secondary effects doctrine also used for laws involving noise, harm to children

The secondary effects doctrine has been applied in cases far removed from the land-use regulation of adult businesses.

Some of the secondary effects cited by government officials include noise, security problems, reduced privacy, appearances of impropriety, employment discrimination, negative effects of gambling, competition in the video-programming market, sexual arousal of readers, and harm to children.

A federal judge in Kentucky used the secondary effects rationale to uphold the constitutionality of a public high school dress code, determining that the code was really aimed at the “secondary effects of student dress,” such as gang activity, violence, and inability to identify campus visitors.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.