New religions such as Scientology often pose special problems for the legal system and the First Amendment. Scientology began life as more of a psychological and philosophical theory than a religion, but in 1953, branches of the Church of Scientology began to appear.

Church of Scientology uses ‘auditing’ to measure mental health

The Church of Scientology was founded by L. Ron Hubbard (1911–1986), a gifted, prolific pulp fiction writer. Because of his background, today the church continues to dispute charges that Hubbard saw the road to founding a religion as also one to wealth (Horwitz 1997: 93–94).

In 1950 Hubbard wrote Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, which examined the relationship between physical and mental health. Hubbard believed that the key to understanding human beings was the human spirit. He likened the human brain to a powerful computer, but one that could be held back by “engrams,” or past negative events, some even from previous lives.

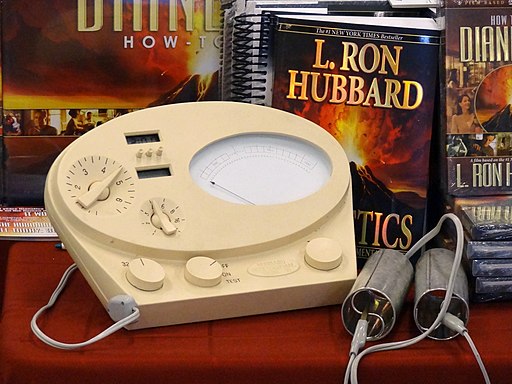

Hubbard suggested that engrams could be overcome by an “auditing” process, in which trained Scientology members would use E-meters—devices that somewhat resemble lie detectors—to measure various bodily reactions.

Appeals court said Scientology fraud claims could not be examined under First Amendment

But allegations about the scientific basis of the church’s treatments led to fraud charges.

After agents of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration seized e-meters and church publications in 1963, a federal appeals court decided in Founding Church of Scientology v. United States (D.C. Cir. 1969) that the claims made about the e-meters were religious ones that the court could not, under United States v. Ballard (1944), properly examine.

A federal court ruled that claims about Scientology’s e-meters were religous ones and could not be examined for falsity under the First Amendment. (Photo of E-Meter by Daniel Spiess, CC-SA-2.0)

Two years later, a district court decision in United States v. Article or Device (1971) was more negative, limiting the use of e-meters to religious counseling and requiring warnings that the devices had not been proven to cure diseases.

Scientology has had other legal problems

Scientology has also spawned lawsuits by former members. In Wollersheim v. Church of Scientology in California (1989), a court awarded tort damages to former member Larry Wollersheim after deciding that the church practices to which Wollersheim had been subjected amounted to the coercive infliction of emotional distress that could not, in context, be considered voluntary.

In other cases, the Church of Scientology has had run-ins with the federal government. In United States v. Heldt (D.C. Cir. 1981), Hubbard’s wife was convicted of conspiring to obstruct justice and steal government documents that might have connected her and her husband to illegal activities.

IRS eventually granted Scientology tax-exempt status

In Hernandez v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue (1989), the Supreme Court upheld a decision by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) denying the deductibility of payments made for Scientology auditing sessions. Under its doctrine of “exchange,” the church required payments for such sessions, and the Court concluded that they therefore represented a quid pro quo exchange rather than a charitable contribution. In 1993, however, the IRS reversed course and decided that it would grant tax-exempt status to the church (see Horwitz 1997: 109).

Despite some legal defeats, the Church of Scientology has generally fared better before U.S. courts than those in other countries (some without equivalent First Amendment protections). Those courts have been more likely to consider Scientology a cult.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.