The right of publicity is a right to legal action, designed to protect the names and likenesses of celebrities against unauthorized exploitation for commercial purposes. Federal appeals court judge Jerome N. Frank coined the term in the case of Haelean Laboratories, Inc. v. Topps Chewing Gum, Inc. (1953), which recognized a baseball player’s interest in his photograph on a baseball card. Scholar J. Thomas McCarthy explains that by inventing a new legal label, “Frank hoped to break the logjam of confusion over the meaning of the word ‘privacy’ ” (51).

Right of publicity differs from right of privacy

Frank distinguished the “right of publicity” from the “right to privacy.” The right to privacy is often traced to an 1890 article in the Harvard Law Review authored by Samuel D. Warren and Louis D. Brandeis. Whereas the right to privacy, including protection against misappropriation, is designed to guard individuals’ personal rights against emotional distress, the right of publicity is recognized as a property right, largely designed to protect the commercial value of the image that a person has cultivated in becoming a celebrity. The right of publicity thus bears some resemblance to copyright law, through which it is sometimes limited and interpreted (Johnson, 2017). Sometimes, it is also interpreted in conjunction with the Lanham Act, which is designed for false endorsement claims, as in trademarks or false advertising.

To date, the right of publicity has been recognized either in state common (judge-made) law or in state statutes, with more than half the states recognizing the right in one form or another. Lloyd Rich, a lawyer and writer in the field of publishing and intellectual property law, writes on the web page of the Publishing Law Center that First Amendment freedoms of speech and press clearly allow sources to include information and pictures relative to “current news items,” “media presentation on ‘public issues,’ ” “factual, educational and historical material,” and “entertainment and amusement concerning interesting aspects of an individual’s identity.”

Court decisions have ruled that protection against the use of unauthorized likenesses can extend to use of “look-alikes” or sound-alikes in commercials. White v. Samsung Electronics America, Inc. (9th Cir. 1992) thus awarded Vanna White, pictured here, damages after Samsung dressed a robot like her and had it turn letters. (Image via Pixabay)

Protections against unauthorized likenesses extend to many circumstances

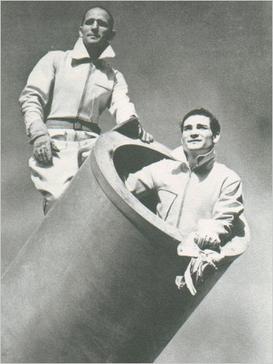

Court decisions have, however, ruled that protection against the use of unauthorized likenesses can extend to use of “look-alikes” or sound-alikes in commercials (White v. Samsung Electronics America, Inc. [9th Cir. 1992] thus awarded Vanna White damages after Samsung dressed a robot like her and had it turn letters, and Midler v. Ford Motor Co. [9th Cir. 1988] awarded damages to Bette Midler after advertisers attempted to imitate her voice for an advertising jingle); use of a signature phrase (as when Carson v. Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets [6th Cir. 1983] protected Johnny Carson’s signature phrase, “Here’s Johnny,” against uncompensated commercial usage); a distinctively marked car; or even a name. In Zacchini v. Scripps-Howard Broadcasting Co. (1977), the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that a television station would have to provide compensation for broadcasting a film clip of a complete human cannonball act.

Right of publicity may extend beyond a celebrity’s lifetime

The right of publicity may extend beyond the lifetime of a celebrity. In Comedy III Productions, Inc. v. Gary Saderup, Inc. (2001), the California Supreme Court ruled that an individual’s charcoal portrayals of the Three Stooges on T-shirts and lithographs constituted violations of the right of publicity rather than art protected by the First Amendment, on the basis that “when an artist’s skill and talent is manifestly subordinated to the overall goal of creating a conventional portrait of a celebrity so as to commercially exploit his or her fame, then the artist’s right of free expression is outweighed by the right of publicity.”

Critics say right of publicity has been unevenly applied

Critics of the right of publicity argue that the concept has proven uneven in its application. Alex Wyman has argued that variations in state laws and wide variation in their application and interpretation call for a common national standard (2014). Eric E. Johnson has argued that the current doctrine actually embraces at least three different concepts. He identifies these as “the endorsement right, the merchandizing entitlement, and the right against virtual impressment” (2017, p. 894).

- The first involves cases “where the plaintiff has been unwittingly contrived to endorse commercial goods or services” (p. 928).

- The merchandizing entitlement is designed to protect celebrities against use of their name or likeness in merchandizing (p. 932).

- Finally, the right against virtual impressment is designed to prevent their unwitting employment (as “to produce a performance that might otherwise require voluntarily supplied labor” (p. 935).

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.