Congress passed the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) of 1970 in an attempt to combat organized crime. The application and use of the law has raised important First Amendment issues implicating the right to freedom of association.

RICO laws attempt to fight organized crime

RICO criminalizes three activities:

- using illegal income to acquire, establish, or operate an enterprise;

- acquiring an interest in such an enterprise; and

- using an enterprise to collect a debt.

In addition, the law makes it an offense to conspire to engage in any of the above activities. Actions defined as racketeering under RICO include extortion, violation of the Hobbs Act of 1948, and other crimes that may interfere with interstate commerce.

RICO’s breadth is significant, applying to any “pattern of racketeering activity,” which is defined as having within the preceding 10 years committed two or more predicate acts — that is, such acts as mail fraud, murder, or trafficking in obscene material on which a subsequent RICO prosecution is based, or predicated. RICO has several civil law provisions that allow for private parties to collect damages if a violation occurs.

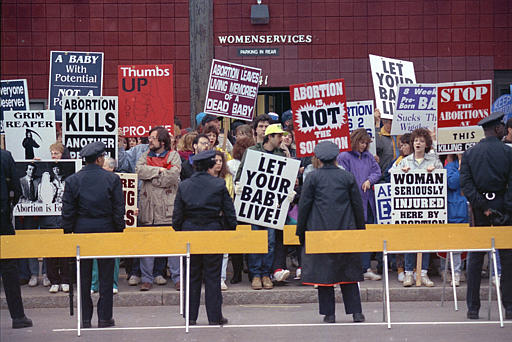

Supreme Court considered using RICO law against organization trying to shut down abortion clinics

Although the main focus and use of RICO is directed toward organized crime, it has also been applied to various white-collar crimes, such as fraud prosecutions. But the most controversial application has involved activity traditionally thought to be covered or protected by the First Amendment.

For example, in Scheidler v. National Organization for Women (1994), the Supreme Court ruled that RICO could be used to collect damages against anti-abortion groups seeking to shut down women’s clinics.

In this case, the National Organization for Women (N.O.W.) sought to collect damages from Operation Rescue, an anti-abortion organization. The Court ruled that the racketeering activity need not have an economic motive. In subsequent decisions, however, including in Scheidler v. National Organization for Women (2006), the Court reversed ground, asserting that the protesters had not obtained property from clinics as required under the Hobbs Act in order to show extortion.

Supreme Court said RICO forfeiture laws used in obscenity case did not violate First Amendment

In Alexander v. United States (1993), the Court ruled that RICO forfeiture laws did not violate the First Amendment.

At issue was an individual convicted of RICO and federal obscenity laws. Because the owner’s conviction for the sale of several obscene products was deemed a pattern of predicate activity, he was ordered to forfeit his businesses and nearly $9 million obtained as a result of racketeering activity.

Claiming that the forfeiture trampled on his First Amendment expressive rights, the owner appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled that because the forfeitures did not constitute a form of prior restraint of speech, they did not violate the First Amendment.

RICO laws continue to be used expansively to combat organized crime. Although the act can be used against protesters, courts and prosecutors are less likely to use it for that purpose than they have in the past.

This article was originally published in 2009. David Schultz is a professor in the Hamline University Departments of Political Science and Legal Studies, and a visiting professor of law at the University of Minnesota. He is a three-time Fulbright scholar and author/editor of more than 35 books and 200 articles, including several encyclopedias on the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court, and money, politics, and the First Amendment.