The controversial decision in Planned Parenthood of the Columbia/Willamette, Inc. v. American Coalition of Life Activists, 290 F.3d 1058 (9th Cir. 2002), by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals determined that anti-abortion speech—including online expression—constituted a true threat and was not protected by the First Amendment.

Court upheld that anti-abortion materials constituted true threats, unprotected by the First Amendment

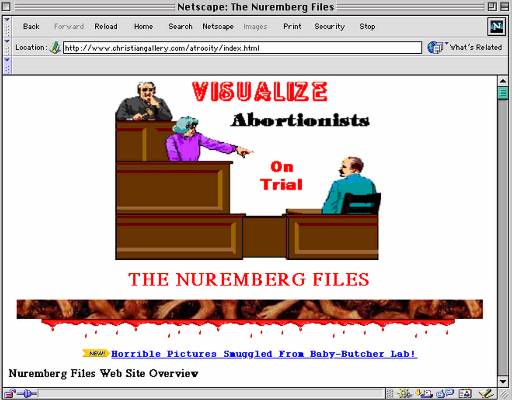

The decision addressed the “threat of force” as defined by the Freedom of Access to Clinics Entrances Act (FACE). The court upheld both an injunction and a heavy fine against the anti-abortion protest group the American Coalition of Life Activists (ACLA) for its publication of “Wanted”-type posters and a “Nuremberg Files” Web site listing the names and addresses of abortion providers who, in the latter case, its authors hoped would one day be tried for “crimes against humanity.” After an initial panel decided to overturn the jury verdict, the court, sitting en banc, upheld a district court decision deciding that, in context, these materials constituted “true threats” that were not protected by the First Amendment.

Majority focused on fact that abortion providers had been murdered

The narrow 6-5 majority focused on the fact that three abortion providers had been murdered after postings of previous posters and that the posters were designed to intimidate, rather than to persuade, the doctors. The majority concluded that although “advocating violence is protected, threatening a person with violence is not.” Given the killing of previous doctors who had been singled out, the majority distinguished “between political hyperbole, which is protected, and true threats, which are not.” The Court decided that a true threat is one “where a reasonable person would foresee that the listener will believe he will be subjected to physical violence upon his person.”

It interpreted the “threat of force” in FACE to be “a statement that, in the entire context and under all the circumstances, a reasonable person would foresee would be interpreted by those to whom the statement is communicated as a serious expression of intent to inflict bodily harm upon that person.” The majority enjoined the continued possession of the posters, arguing that “the posters’ status is more like conduct than speech.”

The decision addressed the “threat of force” as defined by the Freedom of Access to Clinics Entrances Act (FACE). The court upheld both an injunction and a heavy fine against the anti-abortion protest group the American Coalition of Life Activists (ACLA) for its publication of “Wanted”-type posters and a “Nuremberg Files” website listing the names and addresses of abortion providers who, in the latter case, its authors hoped would one day be tried for “crimes against humanity.” After an initial panel decided to overturn the jury verdict, the court, sitting en banc, upheld a district court decision deciding that, in context, these materials constituted “true threats” that were not protected by the First Amendment. The “The Nuremberg Files” website is shown here Tuesday, Feb. 2, 1999. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Dissenters said scope of true threats should have been limited

Judge Alex Kozinski wrote a strong dissent, stating he would have limited the scope of true threats to those in which a speaker (typically face to face) warned individuals of “harm that the speaker controls.” He noted that “the two posters and the web page, by their explicit terms, foreswore the use of violence and advocated lawful means of persuading plaintiffs to stop performing abortions or punishing them for continuing to do so.” He reiterated that “for the statement to be a threat, it must send the message that the speakers themselves—or individuals acting in concert with them—will engage in physical violence.” He believed that there was “no evidence that the defendants who prepared the posters would have been understood by a reasonable listener as saying that they will cause the harm.” He noted, “Coercive speech that is part of public discourse enjoys far greater protection than identical speech made in a purely private context.” He thought the liability verdict, eventually reduced from $108 million to $4.3 million, would have an even greater “chilling effect” than the injunction that the court had issued.

Judge Marsha Berzon also issued a dissent, emphasizing that neither the posters nor the files contained explicit threats and questioning whether “context is sufficient to turn a set of communications that contain speech at the core of the First Amendment’s protections into speech that can be proscribed pursuant to an injunction and compensated for through damages.” She thought that it was essential to show some element of subjective intent before convicting an individual of uttering a true threat. Berzon further feared that the jury was encouraged to hold the defendants liable “for their abstract advocacy of violence rather than for the alleged coded threats in the posters and website, the instructions to the jury to the contrary notwithstanding.”

Some commentators criticized the Ninth Circuit’s decision, believing that the speech at issue should have been analyzed under the standard of incitement to imminent lawless action in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) as opposed to a more flexible true-threats analysis. The U.S. Supreme Court twice rejected appeals of this decision in American Coalition of Life Activists v. Planned Parenthood in 2003 and 2006.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.