In Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations, 413 U.S. 276 (1973), the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of sex-segregated classified advertisements (ads specifying the desired sex of the applicant for the position), finding that the state had leeway in regulating commercial speech and that an ordinance banning employment discrimination did not violate the First Amendment.

Pittsburgh adopted an ordinance banning sex discrimination in employment

The case arose when, in 1969, consistent with the ban on employment discrimination in Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the city of Pittsburgh adopted an ordinance mirroring Title VII’s prohibition on employment discrimination on the basis of sex unless sex is a “bona fide occupational qualification” (BFOQ) — that is, when only persons of the specified sex were able to fulfill the requirements of the job. Among its provisions, the ordinance prohibited anyone from furthering an illegal employment practice.

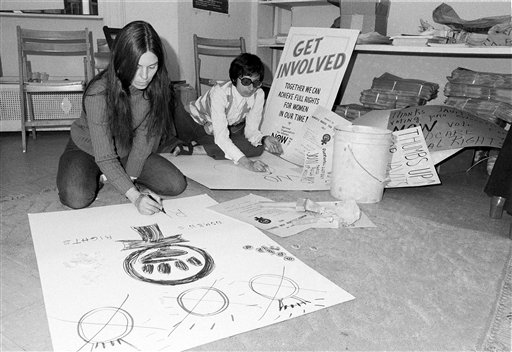

Newspaper allowed sex-designated ads

In October 1969, the National Organization for Women (NOW) filed a complaint with the Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations charging the Pittsburgh Press Company with violating the ordinance by allowing employers to place sex-designated ads for jobs in which sex was not a BFOQ. The Press had placed a disclaimer at the top of each column of ads, stating, “Jobs are arranged under Male and Female classifications for the convenience of our readers. This is done because most jobs generally appeal more to persons of one sex than the other.” The disclaimer also noted that unless the advertisements explicitly specified persons of one sex, readers should assume that persons of both sexes were invited to apply for the position, as the law required.

Newspaper was charged with violating the ordinance

The Pittsburgh Human Relations Commission ruled that the newspaper violated the ordinance and ordered it not to print job advertisements under the labels “Male-Interest” and “Female-Interest” in the future. The lower state court upheld the Commission’s ruling, and the state appellate court modified the lower court order by specifying that sex-designated advertisements were permissible in situations in which employers were free to make sex-based hiring decisions.

Court upheld ordinance

It was up to the Supreme Court to decide whether the ordinance violated the Press’s First Amendment right of freedom of the press. In a 5-4 decision, with Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. announcing the decision, the Court upheld the Commission’s order, basing its decision on the commercial speech doctrine that allows states more leeway in regulating advertisements, or pure commercial speech, as opposed to political speech.

Recognizing the importance of freedom of the press in a free society, the Court characterized the ads as “classic examples of commercial speech.” It rejected the newspaper’s argument that its editorial judgment in deciding where to place the ads was entitled to full First Amendment protection. Additionally, Powell pointed out that the ads were not simply about commerce but about illegal commerce and that a newspaper could surely be prohibited from running an ad advertising illegal drugs or other illegal products. Thus, the Court held that the Commission’s order did not infringe on the Press’s First Amendment right.

Dissenters thought First Amendment freedom of the press included advertisements

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger and Justices William O. Douglas, Potter Stewart, and Harry A. Blackmun all wrote dissenting opinions. Chief Justice Burger wrote that “the First Amendment freedom of press includes the right of a newspaper to arrange the content of its paper, whether it be news items, editorials, or advertising, as it sees fit.”

Stewart, arguably the Court’s premier defender of freedom of the press, wrote that the First Amendment “is a clear command that government must never be allowed to lay its heavy editorial hand on any newspaper in this country.”

Douglas, who joined Stewart’s dissent, wrote separately to emphasize his belief that the First Amendment prohibits censorship of a newspaper’s content.

Blackmun wrote to say he generally agreed with Stewart’s analysis other than the paragraph in which Stewart opined: “So long as Members of this Court view the First Amendment as no more than a set of ‘values’ to be balanced against other ‘values,’ that Amendment will remain in grave jeopardy.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Susan Gluck Mezey is a professor emeritus of political science at Loyola University Chicago; she holds an M.A. and Ph.D. from Syracuse University and a J.D. from DePaul University. She has published in the area of minority group policies and the federal courts. Her recent books include: Transgender Rights: From Obama to Trump (2020); Beyond Marriage: Continuing Battles for LGBT Rights (2017); Elusive Equality: Women’s Rights, Public Policy, and the Law, 2d Ed. (2011); Gay Families and the Courts: The Quest for Equal Rights (2009); Queers in Court: Gay Rights Law and Public Policy (2007); and Disabling Interpretations: Judicial Implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (2005).