The term original intent refers to the notion that the judiciary should interpret the Constitution (including its amendments) in accordance with the understanding of its framers. The courts’ commitment to original intent is somewhat tested, however, by the reality that the framers’ intentions are not always easy to identify.

Another factor is that it has never been clear to what extent the framers’ intentions are relevant to the task of establishing constitutional norms. Some even disagreed on this point. James Madison, one of the drafters of the Constitution, felt strongly that future interpretation of the document should not rest primarily on the intentions of the framers, but on the intentions of the people who, through their state representatives, ratified the Constitution. In part, this reasoning explains Madison’s decision not to make public for many years the notes he took at the Constitutional Convention.

Alexander Hamilton, who signed the Constitution on behalf of New York, looked to the Constitution itself, believing that the text should control its interpretation. In his view, the Constitution spoke for itself; there was no need to go behind it to ascertain the intent of the framers. However, in what it says, the Constitution is liberal in granting powers to the national government.

Jefferson advocated for strict constructionism

Thomas Jefferson advocated still another method of constitutional interpretation: the rule of strict constructionism. Jefferson strongly asserted that the Constitution and Bill of Rights were grounded in the principle embodied in the Tenth Amendment: that all undelegated powers are reserved “to the states respectively, or to the people.” Yet even Jefferson violated his interpretive theory when, after originally concluding that the Louisiana Purchase required a constitutional amendment, he authorized the transaction without one.

Original intent of the Bill of Rights

It can be unclear what the framers were thinking when they drafted the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights was not a part of the document drafted at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Almost all the delegates believed a bill of rights would be superfluous. The new federal government possessed only limited powers delegated to it by the states; no power had been granted to legislate on any of the subjects that might be included in a bill of rights. Therefore, an enumeration of rights was not necessary.

From late 1787 until 1789, the proposed Constitution was considered by the various state ratifying conventions. Meanwhile, a strong Anti-Federalist element developed quickly. The Anti-Federalists opposed ratification, fearing that the centralizing tendencies of the new document would crush the rights of states and individuals. For many of the states, the only solution to this problem was to mandate inclusion of a bill of rights. Indeed, six of the 13 states — Massachusetts, New Hampshire, North Carolina, New York, Rhode Island, and Virginia — accompanied their instruments of ratification with a list of recommended amendments that would secure various personal liberties, such as “rights of conscience,” “liberty of the press,” and “rights of trial by jury.” However, the records of the debates of the state ratifying conventions are of little help in ascertaining the precise meanings that such liberties were to assume.

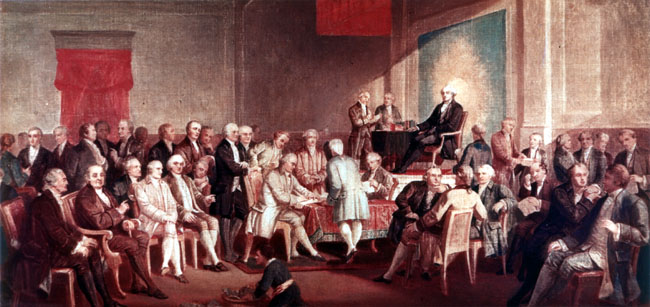

It can be unclear what the framers were thinking when they drafted the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights was not a part of the document drafted at the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Almost all the delegates believed a bill of rights would be superfluous. The new federal government possessed only limited powers delegated to it by the states; no power had been granted to legislate on any of the subjects that might be included in a bill of rights. Therefore, an enumeration of rights was not necessary.(Another image of the signing of the Constitution, painted by Thomas P. Rossiter between 1860-1870, public domain)

Different ways religion clauses of the First Amendment have been interpreted

The first rights enumerated in the First Amendment pertain to religion: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Of the six states that recommended amendments to secure personal liberties, all but Massachusetts submitted proposals about religious freedom. Apparently, Massachusetts legislators did not feel that the Massachusetts religious establishments were in any way threatened by the proposed Constitution; they believed that the new federal government was to be impotent in matters of religion.

For the religion clauses, two basic interpretations of what the constitutional framers intended have emerged — the separationist and the accommodationist. The separationist interpretation suggests a strict separation between civil authority and religion. Although governmental authority should protect the private “free exercise” of religion, no church or religious group should receive any form of governmental aid. The accommodationist view holds that the framers intended for the establishment clause to prevent governmental establishment of a single sect or denomination of religion over others.The framers, they contend, intended only to keep the government from abridging religious liberty by discriminatory practices generally or by favoring one denomination or sect over others. Neither view, however, was well articulated, nor can either claim to have represented the clearly understood meaning of the religion clauses in 1789.

Most think framers had broad intent with First Amendment

As for the remaining rights enumerated in the First Amendment, it is equally unclear exactly what the framers were thinking. Most scholars believe they were thinking rather broadly, with few restrictions on the rights enumerated. Virtually everyone agrees that First Amendment rights were fundamentally limitations on federal and not state power. Thus there was little reason to interpret the various rights. In fact, from the time the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791 until World War I, Congress passed only one law restricting speech — the Sedition Act of 1798. It was not until the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 that an intense debate over the meaning of the free speech clause began. That debate, like the meaning of all of the First Amendment rights, has largely played out in the courts.

Noting the confusion that has surrounded the Supreme Court’s efforts to return to the Founders’ understanding of the Second Amendment right to bear arms, Professors Jacob D. Charles and Matthew L. Schafer have recently cautioned that at the time they ratified the First Amendment, many states enforced “laws criminalizing blasphemy, government criticism, tepid and other speech viewed to be bad or harmful” (2024), but which have been protected by 20th century precedents, which they think the Constitution should continue to recognize.

As for freedom of the press, if there was anything close to a consensus in the founding era it was likely the common law view expressed by English jurist William Blackstone: “The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published” (Blackstone 1872: 4:151).

Few suggest that there should be no limits on speech, press, assembly, and redress rights. Rather, the debate is over where to draw the line between protected and nonprotected expression. In some areas, such as pornography and flag burning, it is exceedingly difficult to know where to draw the line. Individual interests are pitted against society’s larger interests, and the courts do the line drawing. Whether the courts’ decisions conform to the framers’ original intent will always be a matter of considerable debate.

This article was originally published in 2009. Derek H. Davis is the former director of the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies and editor of Journal of Church and State. He is also the former director of the University of Mary-Hardin Baylor Center for Religious Liberty. He now practices law in Dallas, Texas. He is the author or editor of nineteen books and has also published more than 150 articles in various journals and periodicals. He serves numerous organizations given to the protection of religious freedom in American and international contexts.