In Ollman v. Evans, 471 U.S. 1127 (1985), the U.S. Supreme Court denied a writ of certiorari in a case alleging libel in which then Justice William Rehnquist and Chief Justice Warren Burger dissented.

Marxist professor sues columnists for defamation

Bertell Ollman, an avowed Marxist political science professor at New York University who had been considered for a position as head of the Government and Politics Department at the University of Maryland, had sued columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak for defamation. They had published an article that likely contributed to the decision by the president of the University of Maryland not to hire Ollman.

The article had alleged that Ollman was more interested in political advocacy than scholarship. They had quoted an unnamed political scientist as saying that “Ollman has no status within the profession, but is a pure and simple activist.”

Lower court says statement was opinion

Largely relying on the Supreme Court decision in Gertz v. Welch (1974), the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia had held that because the central statement in question was a matter of opinion rather than of fact, the First Amendment provided absolute protection.

The U.S. Court of Appeals had affirmed this decision in a divided opinion. The Supreme Court rejected review of the case, which allowed the appellate court’s ruling to stand.

Some justices did not think statement was protected ‘opinion’

Justice Rehnquist’s dissent to the denial of cert, which Chief Justice Burger had joined, considered the circuit court decision to be “extraordinary.”

Rehnquist observed that “the common law of defamation” recognized that some statements were so damaging to reputation that they were considered to be “slander per se.” Although he had concurred in the opinion in Gertz, he explained that “I regarded this statement as an exposition of the classical views of Thomas Jefferson and Oliver Wendell Holmes that there was no such thing as a false ‘idea’ in the political sense, and that the test for truth for political ideas is indeed the marketplace and not the courtroom.”

He thought that the circuit court majority had used the distinction between statements of fact and opinion as a “meat axe” that was “totally oblivious ‘of the rich and complex history of the struggle of the common law to deal with this problem.” He argued that the statement about Ollman’s status within the profession was not merely an opinion, but a purported statement of fact that the Court should have been able to assess for its truthfulness.

Circuit Court analyzed statement, professor’s role as political activist

The circuit court decision that the Supreme Court affirmed in this case is fascinating both for the opinions expressed and the judges who rendered them.

Judge Kenneth Starr’s majority opinion

Judge Kenneth Starr, who would later lead investigations of President Bill Clinton, wrote in his opinion that “the challenged statements are entitled to absolute First Amendment protection as expressions of opinion.”

Starr went on to articulate a four-part test to assess the totality of circumstances under which statements were made. These involved analysis of “the common usage or meaning of the specific language of the challenged statement itself”; “the degree to which the statements are verifiable”; “the context in which the statement occurs”; and “the broader social context into which the statement fits.” Applying these standards, Starr did not believe that Evans and Novak had committed libel.

Because Ollman had engaged in political activism, Starr believed that he was a public figure under the standards for libel established in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964).

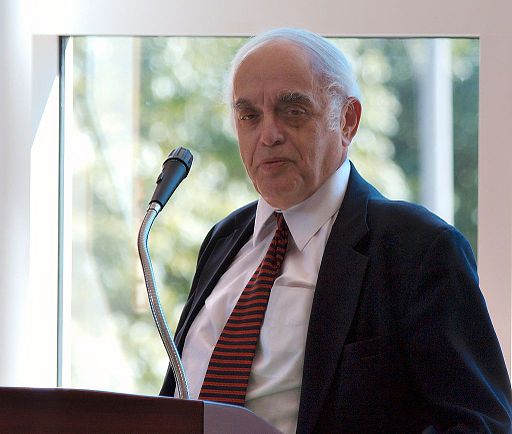

Judge Robert Bork’s Opinion

Judge Robert Bork, whose nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court would later be rejected, filed a concurring opinion that was joined by other judges including Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who would later serve on the Supreme Court. Noting that Ollman had asked for considerable monetary damages, Bork observed that:

It arouses concern that a freshening stream of libel actions, which often seem as much designed to punish writers and publications as to recover damages for real injuries, may threaten the public and constitutional interest in free, and frequently rough, discussion. Those who step into areas of public dispute, who choose the pleasures and distractions of controversy, must be willing to bear criticism, disparagement, and even wounding assessments.

Fearing that Starr’s majority opinion leaned toward “mechanical jurisprudence,” Bork emphasized a more flexible approach on original intent than Judge Antonin Scalia (who later became a Supreme Court justice) articulated in his dissent. Agreeing that judges should be wary of “creating new constitutional rights or principles,” Bork explained that it was still necessary for judges “to discern how the framers’ values, defined in the context of the world they knew, apply to the world we know.” Arguing that the Fourth Amendment had to be adapted to a world with electronic surveillance and the commerce clause to trailer trucks, he also noted the need to apply First Amendment principles to new technologies.

Even if the framers of the First Amendment had not envisioned libel actions as a threat in their day, “if, over time, the libel action becomes a threat to the central meaning of the first amendment, why should not judges adapt their doctrines? Why is it different to refine and evolve doctrine here, so long as one is faithful to the basic meaning of the amendment?” Using what he called a balancing test,” Bork upheld the lower court decision.

Judge Antonin Scalia’s Opinion

In his dissent, Scalia argued that the article at issue “seems to me a classic and cooly crafted libel.” Opposing the idea of “balancing,” or evolution, Scalia argued that “It seems to me that the identification of ‘modern problems’ to be remedied is quintessentially legislative rather than judicial business—largely because it is such a subjective judgment; and that the remedies are to be sought through democratic change rather than through judicial pronouncement that the Constitution now prohibits what it dd not prohibit before.”

Majority concerned excessive damage awards would suppress speech

This case presents many of the issues that surround recent controversies over whether the Supreme Court should reconsider the actual malice standard that it established for public figures in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. The majority’s concern that excessive damage awards might suppress First Amendment speech and press protections are also relevant to concerns raised by SLAPP suits and laws designed to deter them.

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.