Especially in the era prior to the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited racial discrimination in most places of public accommodation, picketing and boycotting businesses that were practicing racial discrimination proved to be important tools for the civil rights movement. These tools are strongly tied to First Amendment rights of expression.

In New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co., Inc. 303 U.S. 553 (1938), the U.S. Supreme Court created a precedent that proved to be helpful in later boycotts like the Montgomery Bus boycott of 1955 and 1956, the Birmingham Campaign of 1963, and similar actions. The case primarily centered on an interpretation of the Norris-La Guardia Act, which governed labor disputes.

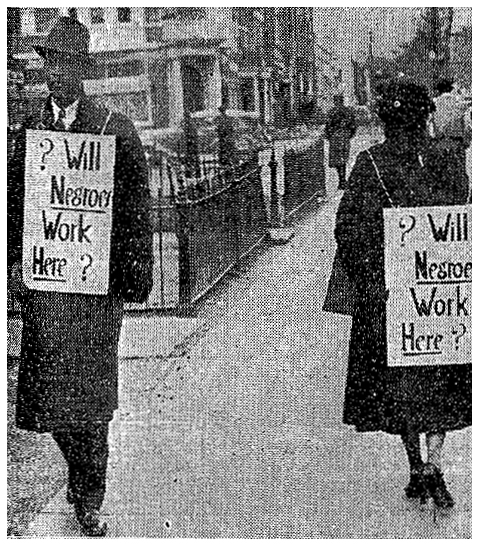

New Negro Allianced picketed grocery stores that did not hire blacks

The case began when the Sanitary Grocery Company, a Delaware corporation that owned 255 retail grocery, meat, and vegetable stores, successfully sought an injunction against the New Negro Alliance in the U.S. District Court in Washington, D.C., which was affirmed by the D.C. Court of Appeals. The New Negro Alliance had boycotted some of the Company’s stores as part of a larger Jobs-For-Negroes movement, which sought to pressure the owners of these stores, especially those in African American neighborhoods, to employ members of those communities.

In a decision written by Justice Owen Roberts, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that, contrary to the interpretations of the lower courts, the case was a labor dispute that was governed by the Norris-La Guardian Act, which had extended provisions in the Clayton Act limiting the use of judicial injunctions in such labor disputes.

Court ruled that peaceful demonstration did not violate law

Contrary to company allegations, Roberts concluded that the protests had involved a single individual carrying a placard that said “Do Your Part! Buy Where You Can Work! No Negroes Employed Here!” and did not involve physical intimidation, coercion, obstruction, or harassment.

Roberts further ruled that the law “intended that peaceful and orderly dissemination of information by those defined as persons interested in a labor dispute concerning ‘terms and conditions of employment’ in an industry or a plant or place of business should be lawful” and that “short of fraud, breach of the peace, violence, or conduct otherwise unlawful, those having a direct interest in such terms and conditions of employment should be at liberty to advertise and disseminate facts and information with regard to terms and conditions of employment, and peacefully to persuade others to concur in their views respecting an employer’s practices.” He therefore reversed the orders of the lower court and allowed the protest to continue.

Justice Benjamin Cardozo did not participate in this case. By contrast, Justice James McReynolds wrote a brief but spirited dissent, joined by Pierce Butler, denying that the case involved a true labor dispute. He expressed fears that “Under the tortured meaning now attributed to the words ‘labor dispute,’ no employer-merchant, manufacturer, builder, cobbler, housekeeper or whatnot-who prefers helpers of one color or class can find adequate safeguard against intolerable violations of his freedom if members of some other class, religion, race, or color demand that he give them precedence.”

The boycott in this and other cases have been credited with helping to secure jobs for numerous African Americans. Moreover, many members of the New Negro Alliance went on to become influential leaders in the civil rights movement (Shiell 2019, 67).

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was published on April 3, 2020.