In Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. NAACP, 366 U.S. 293 (1961), the Supreme Court decided that requiring an organization to submit its membership lists to the state violates First Amendment free association rights if this disclosure can reasonably be expected to result in discrimination against the members.

Louisiana law required NAACP to submit membership lists, swear no communist connections

To do business in Louisiana, “non-trading” organizations were required to submit an affidavit stating that they were not affiliated with any out-of-state associations having links to communist or subversive organizations or communists on their board.

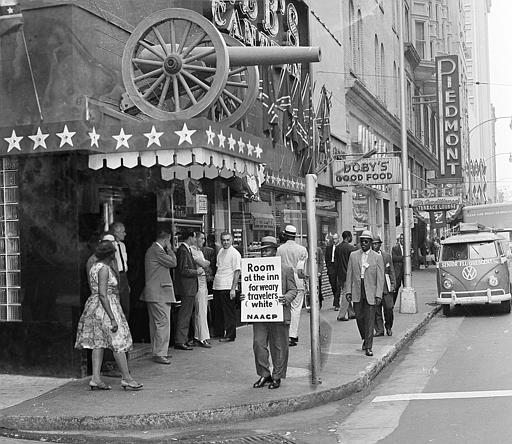

In addition, any non-trading organization affiliated with any out-of-state association was required to submit its membership list to the state of Louisiana. For failure to comply with these laws, Louisiana sued the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) in state court to stop it from operating in Louisiana. The NAACP had the case moved to federal district court, which enjoined the state from enforcing either of the statutes, and Louisiana appealed to the Supreme Court.

Court said ‘impossible’ for NAACP to swear that no members had communist affiliations

Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice William O. Douglas affirmed the decision of the lower federal court. Douglas agreed that it is virtually “impossible” to require officers in the Louisiana NAACP to swear that no board members in the national or other local chapters have affiliations with communist or other subversive organizations. Such a requirement is “not consonant with due process” because it requires “a person to swear to a fact that he cannot be expected to know” or to “refrain from a wholly lawful activity” — to organize people with like-minded interests.

Court said requiring membership list violated First Amendment, had chilling effect

The second statute required an organization to submit an annual list of members, complete with addresses. Noncomplying organizations were prohibited from meeting in Louisiana, and officers and members could face criminal charges.

The Court noted that Louisiana enacted this law in 1924 to curb the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and that it has never been enforced against any other organization until the present case. Although the state denied all allegations of discrimination, members and officers of several local Louisiana affiliates of the NAACP testified in lower court that after they complied with the law, they were “subjected to economic reprisals.” Douglas asserted that although the issue of reprisals was in question and would be resolved through future hearings, the NAACP did have standing in this case.

Citing NAACP v. Alabama (1958), Douglas wrote that the Louisiana case was similar because it dealt with “a constitutional right, since freedom of association is included in the bundle of First Amendment rights made applicable to the States by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.” If compliance with the law “results in reprisals against and hostility to the members, disclosure is not required.” Such a law would have a chilling effect on both the rights of association and of speech.

Government cannot pursue legitimate interests by stifling personal liberties

To illustrate, Douglas relied on Shelton v. Tucker (1960), which struck down an Arkansas law requiring all public school teachers to submit a list of all organizations in which they were members or to which they contributed money. Although the stated purpose of the law was legitimate — to ensure the competence of public teachers — “that purpose cannot be pursued by means that broadly stifle fundamental personal liberties when the end can be more narrowly achieved.”

Douglas concluded, however, that states may have legitimate and compelling governmental interests in regulating speech and behavior. Citing a variety of cases dealing with restrictions on the distribution of literature within a community, the Court conceded that such regulations have been upheld when they do not adversely affect the exercise of otherwise constitutional rights.

This article was originally published in 2009.