The theory of license has its origins in antiquity and is derivative of the authority of the sovereign. The Oxford English Dictionary defines license as “a permit from an authority to own, use, or do something.” Anglo-American common law tradition includes sovereign authorization of exclusive rights through patents, copyrights, licenses, issuances, permits, proprietaries, prerogatives, and other privileges.

Licensing laws in United States must be balanced with First Amendment protections

In the United States, the power to grant and require licenses is balanced by the constitutional protections of federalism. Under the First Amendment, such licenses require carefully crafted legislation and administrative regulations to ensure that their impingement upon guaranteed rights is minimized while the promotion of targeted public policies is maximized.

Licensing powers are concurrently exercised in the United States by federal, state, and local governments. The licensure of business operations through permits is traditionally a state or local power, while regulation of corporate activities is primarily a federal power based on the commerce clause.

The regulation of inventions and creative works through copyrights and patents is primarily a federal power enumerated in Article 1, section 8, of the Constitution. This federal power is complemented by state regulation of trade secrets, rights of publicity, and to the extent not limited by federal power, common law copyright protection. Trademarks and trade secrets are regulated by a combination of federal and state authority. The federal government derives from the commerce clause its authority to regulate these types of intellectual property.

Licensing involving expressive speech rights can trigger judicial review

The licensing of actions not commonly associated with expression is given little, if any, First Amendment scrutiny.

As the Supreme Court noted in City of Lakewood v. Plain Dealer Publishing Co. (1988):

“Laws of general application that are not aimed at conduct commonly associated with expression and do not permit licensing determinations to be made on the basis of ongoing expression or the words about to be spoken, carry little danger of censorship.”

The licensing of expressive acts, however, must be carefully reviewed. In cases where regulations discriminate on the basis of the content of speech, the Court will apply a strict scrutiny standard that it would not apply in the case of content-neutral regulations.

A federal appeals court thus observed in Bery v. City of New York (2d Cir. 1996):

“A content-neutral regulation may restrict time, place, and manner of protected speech, provided it is ‘narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest’ and ‘leaves open ample alternative channels for communication.’ ”

Court has upheld federal government’s right to regulate speech, but laws must have safeguards

The Supreme Court has upheld the right of the federal government to regulate businesses and individuals engaged in interstate and international communication despite First Amendment concerns.

In Federal Communications Commission v. Pottsville Broadcasting Co. (1940), the Court upheld the regulation of radio frequencies on the grounds of “public convenience, interest, or necessity” and in National Broadcasting Co. v. United States (1943) asserted, “The facilities of radio are limited and therefore precious; they cannot be left to wasteful use without detriment to the public interest.” Similar regulation now extends to television, wire, satellite, and cable communications.

State and local entities have established the right to regulate adult bookstores and related businesses engaging in expressive activities through the issuance of licenses, although such businesses clearly have First Amendment protections.

This right to regulate, however, is not unfettered. The licensing laws must have procedural safeguards against censorship.

As the Court held in FW/PBS, Inc. v. City of Dallas (1990):

“the licensor must make the decision whether to issue a license within a specified and reasonable time period during which the status quo is maintained, and there must be the possibility of prompt judicial review in the event that the license is erroneously denied.”

Furthermore, governments “cannot make arbitrary distinctions based on the manner of speech or the media used for publication,” as stated in Forsalebyowner.com v. California Department of Real Estate (E.D. Cal. 2004).

Authorities can only regulate time, place and manner of public demonstrations

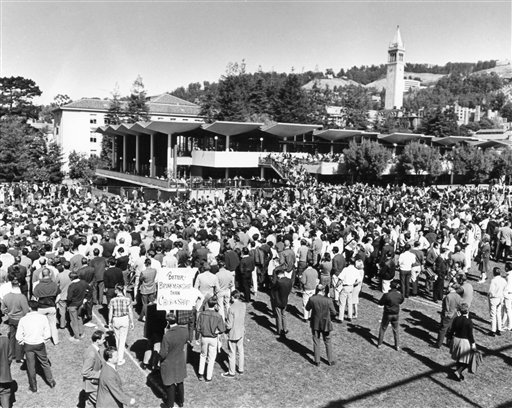

Scene on the University of California campus in Berkeley as a demonstration protesting U.S. presence in Vietnam in 1965. Police refused to grant a parade permit for a march against the Oakland army terminal, but the anti-Vietnam group leaders said they would march anyway. Permit laws that restrict First Amendment rights must not be based on the content of the speech and can only regulate the time, place and manner of the speech. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Governmental entities also may require licenses regulating individuals engaging in clearly expressive acts — such as parades and other public demonstrations.

But as the Supreme Court held in Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham (1969), “a law subjecting the exercise of First Amendment freedoms to the prior restraint of a license, without narrow, objective, and definite standards to guide the licensing authority, is unconstitutional.” Licenses must not be “contingent upon the uncontrolled will of an official,” and “a person faced with such an unconstitutional licensing law may ignore it and engage with impunity in the exercise of the right of free expression for which the law purports to require a license.”

The courts recognize that there is a legitimate state interest in controlling the access and movement of traffic on streets and sidewalks, but as determined in Cox v. Louisiana (1965), a licensing authority merely has the authority to specify the “time, place, duration, or manner” of a parade or public demonstration.

Licenses that protect intellectual property may restrict free speech of others

Governmental entities can also grant licenses, or property rights, to individuals allowing them to exclude others from the use of certain works. Although such exclusionary rights implicate the free speech rights of others, the scope of such licenses must be limited and carefully tailored to advance certain public policies, such as the promotion of science and the arts, the protection of consumers, and the prevention of unfair business practices.

Congress has developed different sets of laws relating to different types of intellectual property. A patent owner is granted the right to exclude others from selling, making, or using an invention for the term of the patent. Although the granting of patents can result in First Amendment concerns, the state interest in promoting invention and progress in science outweighs such concerns.

Congress has carefully developed a series of administrative regulations that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) uses for all patent applicants so that it may confirm that all patents issued actually promote this state interest. The USPTO requires that all patent applicants first demonstrate sufficient novelty, utility, and enablement and carefully comply with detailed administrative procedures and requirements for a patent to be granted.

Copyright law has fair use exception protecting speech

Copyright law grants authors and their heirs or assignees the right to control reproduction or use of their works for a limited duration. This grant is limited by a number of legislative and judicial concepts, including the fair use exception, the idea-expression dichotomy (recognizing that ideas cannot be copyrighted, but their particular expression can be), the first sale doctrine, and certain compulsory licenses.

The fair use exception allows the public to benefit from use of a copyrighted work for certain limited purposes, including the right to comment upon, criticize, or parody the copyrighted work, as illustrated in the case Sony Corp. v. Universal City Studios (1984). The first sale doctrine allows the owners of a copy of a copyrighted work to sell, rent, or destroy their copy of the work without obtaining permission of the copyright owner. Compulsory licenses — which allow an owner’s protected material to be used without the owner’s permission under certain circumstances in return for royalties or a fee — apply to mechanical reproduction of musical compositions and to some vital pharmaceuticals.

Cybersquatting has presented questions in trademark protections

Trademark protections comprise another category of licenses that state and federal governments grant. Laws generally allow trademark owners to prevent the use of their trademark in a manner that is likely to result in consumer confusion. Not all names or logos, however, can be protected as a trademark. Trademarks must be either “strong,” that is, inherently distinctive, or have developed sufficient consumer awareness or secondary meaning associated with the sale and advertisement of particular goods or services.

The trademark owner must then comply with various federal and state legislative and administrative requirements, including actual or intended use in commerce, in order to maintain trademark rights. In a manner similar to the practice in copyright law, trademark owners are also subject to legislative and judicial restrictions, such as the fair use doctrine.

Court rulings in KP Permanent Make-Up, Inc. v. Lasting Impression I, Inc. (2004) and TMI Inc. v. Maxwell (5th Cir. 2004) illustrate these points, and the TMI holding notes that the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act of 1999 does not preclude the defense of fair use of another’s trademark for noncommercial purposes in an Internet domain name.

Trade secret protection is another government license issue

The protection of trade secrets constitutes another form of governmentally granted license.

Most states have adopted in large part the Uniform Trade Secrets Act. It allows entities to reap the rewards of their labor and to maintain standards of business ethics. A California court ruled in DVDCopyControl Association, Inc. v. Bunner (2003) that a “trade secret neither involves a matter of public concern nor implicates the core purpose of the First Amendment.” State courts have accordingly ordered nondisclosure of trade secret information.

This article was originally published in 2009. Lynnette Noblitt is a professor of government at Eastern Kentucky University. Michael W. Hail (1966-2020) was a professor of political science at Morehead State University.