The First Amendment establishment and free exercise clauses represented an implicit promise to Jews, and members of other minority faiths, that the New World offered them the opportunity to exercise their faith freely and without being regarded as second-class citizens.

Early American leaders insisted America was a Christian nation even after the First Amendment

George Washington was among those early American leaders who expressed the judgment that the United States should protect the liberty of conscience of all citizens, including Jews. However, even after the adoption of the First Amendment, other leaders continued to insist that the United States was a Christian nation.

For example, Justice Joseph Story advanced the view (with which Thomas Jefferson disagreed) that U.S. common law embodied Christian principles. Daniel Webster argued before the Supreme Court in Vidal v. Girard’s Executors (1844) that “the preservation of Christianity is one of the main ends of government.” (He did, however, later change his mind; he lost the case on other grounds.) He also called schools “for the propagation of Judaism” illegitimate. In Church of the Holy Trinity v. the United States (1892), Justice David J. Brewer opined, “We find everywhere a clear recognition of the same truth: This is a Christian nation.” In United States v. Macintosh (1931), the Court described Americans as “a Christian people.”

Jewish Americans responded in two different ways

Jewish Americans formulated two kinds of responses to these kinds of “Christian America” claims. The accommodationist social relations model stressed the broadly religious versus the narrowly Christian character of Americans. The legal reform model emphasized the separation of church and state and the importance of the secular nature of the U.S. government. Each response reflected a different reading of history, allied Jewish leaders with different groups, and translated into radically different policy positions.

Social relations response emphasized public relations

Although the period 1916–1939 witnessed the appointment of three Jewish justices—Louis D. Brandeis, Benjamin N. Cardozo, and Felix Frankfurter—to the Supreme Court, the major national Jewish advocacy organizations— American Jewish Committee (founded in 1906), Anti- Defamation League (ADL) of B’nai B’rith (1913), and American Jewish Congress (1918)—maintained a low profile on church-state issues. They feared that concerted action to challenge majoritarian religion practices, such as school prayer and aid to parochial education, would stir up latent anti-Semitism and raise questions about the loyalty of Jews to American values. Thus Jewish organizations initially relied on the social relations model, which emphasized public education and public relations efforts, interfaith negotiations to enlist the support of sympathetic Christian denominations, and compromise with public officials over what religious values and methods of instruction government could aid.

Legal reform response emphasized litigation and legislation

In time, however, Jewish organizations, led by the American Jewish Congress, realized that to influence public policy they would have to augment the social relations model with a legal reform model that emphasized litigation and legislation to rectify inequalities in the law between majority and minority religions. This strategy had two main elements: attacking the discrimination against Jews in colleges, universities, and housing and using law and litigation to bring issues of church-state separation to the courts, thereby promoting policy change.

Jewish School children sing at a New York assembly in 1943, to protest Hitler’s atrocities in Nazi-occupied countries. Jewish organizations disagree on the constitutionality of government-funded religious schools. The American Jewish Committee opposes aid to religious schools, but more Orthodox organizations publicly support state aid for religious schools and school vouchers. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Supreme Court cases made Jewish organizations start to use federal courts

Two 1940s Supreme Court cases, neither of which was brought by Jews, changed the public policy picture for Jewish groups. In Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), the justices applied the free exercise of religion clause of the First Amendment to the states, and in Everson v. Board of Education (1947) they held that the establishment clause of the First Amendment also applied to the states via the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Only after Everson did Jewish groups use the courts to secure principles that treated them, other minority religions, and nonbelievers as equals.

In Everson, the issue was whether the use of public funds by the state of New Jersey to pay for travel to school for all children, including those in parochial schools, violated the Constitution. The Court said it did not, but in doing so it established the principle of separation of church and state, which in later cases led to constitutional limitations on public aid to parochial schools. Because the American Jewish Congress did not have the support of other Jewish organizations and because it feared alienating Catholic groups under the social relations model, it chose not to submit an amicus brief in Everson, even though all the major Jewish organizations opposed the New Jersey law.

American Jewish Congress established Commission on Law and Social Action to oversee legal strategies of Jewish groups

The decision in Everson forced the major Jewish organizations to reevaluate their collective strategies on church-state relations and to consider using the federal courts to secure the policies they were seeking. All the organizations favored a nonsectarian public education system supported by First Amendment principles and the separation of church and state. However, after Everson at first only the American Jewish Congress was prepared to favor a litigation strategy over a social relations one. Led by a young staff attorney, Leo Pfeffer, the American Jewish Congress sought to emulate the techniques of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) by establishing in 1945 its Commission on Law and Social Action (CLSA), which to this day oversees the legal strategy of major Jewish groups.

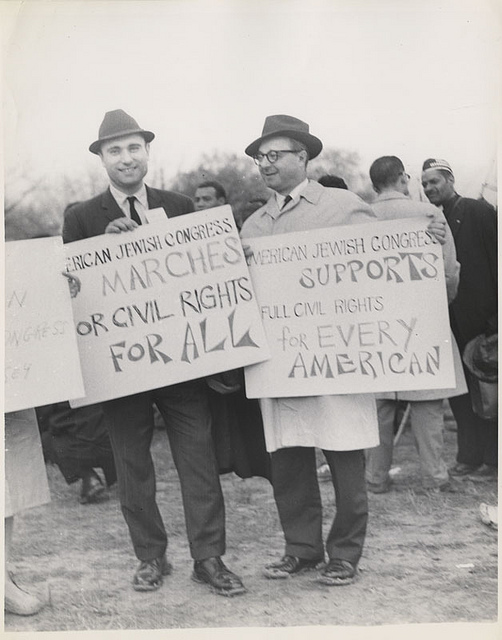

American Jewish Congress members hold signs at the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965. The American Jewish Congress was instrumental in starting the process of influencing public policy through litigation and legislation in order to rectify inequalities between majority and minority religions. (Public domain, American Jewish Historical Society.)

CLSA participates in establishment and free exercise cases

Over the years, the CLSA has participated in many of the leading establishment and free exercise cases decided by the Supreme Court, including Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), which banned state-sponsored “voluntary” Bible reading in public schools.

In two crucial cases, the ADL and American Jewish Committee were content to let Pfeffer and the American Jewish Congress handle the trial phases. In Tilton v. Richardson (1971), the Supreme Court permitted the federal government to provide grants to church-sponsored higher educational institutions for the construction of non-religious school facilities, and in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971) the Court set the test under which courts would decide whether a state program or action violates the establishment clause. When it became clear that the decisions in these cases would significantly affect the constitutionality of parochial school aid, which they opposed, the ADL, the American Jewish Committee, and the constituent organizations of the National Community Relations Advisory Council filed amicus briefs.

American Jewish Committee tried an interfaith approach

The American Jewish Committee has responded to the growth of the religious right by again trying an interfaith approach, joining with non-Jewish organizations, such as the National Council of Churches, in cases such as Lynch v. Donnelly (1984) and County of Allegheny v. American Civil Liberties Union (1989), which addressed the constitutionality of religious symbols, the crèche and menorah, respectively, in holiday displays. In Wallace v. Jaffree (1985), the Court ruled on the constitutionality of whether one minute could be set aside at the start of the school day for meditation or voluntary prayer.

Jewish organizations are not always united in their approaches and positions

Leading Jewish organizations are not always united on whether to pursue litigation under the religion clauses and on what position to take. For example, by the end of the 20th century the separationist consensus in the American Jewish community was coming under increasing pressure from Orthodox Jewish organizations that publicly supported state aid to attend parochial schools, including their own, and the constitutionality of government vouchers to attend such schools.

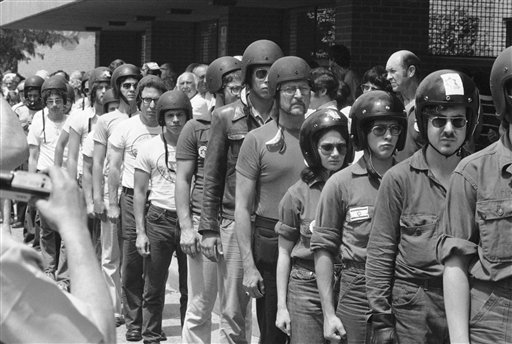

Members of the Jewish Defense League donned helmets as they arrived in Skokie in 1977. The organization was part of the counter-demonstrations against a planned march by the National Socialist Party of America (NSPA), a group that incited anti-Semitism. The majority of the population of Skokie was Jewish, and many were Holocaust survivors. The town did not give the NSPA a permit, but the Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the NSPA had a First Amendment right to demonstrate. (AP Photo/CEK, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Several religion clause cases have related directly to the Jewish community

That said, several important cases under the religion clauses raised issues related directly to the Jewish community. In Braunfeld v. Brown (1961), an Orthodox Jew, whose religious convictions kept him from opening his store on Saturday, the Sabbath, challenged Pennsylvania’s blue law (it required businesses to close on Sunday) as a violation of the religious liberty clauses—he needed to open his store six days a week for economic reasons. The Court, however, upheld the law. All three major Jewish groups opposed Sunday closing laws as forms of state religious establishment that also impinged on religious liberty.

In the late 1970s, another important case, Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America (Ill) (1978), addressed the controversial question of whether Nazis should be enjoined from wearing their swastikas and uniforms and marching in Skokie, Illinois, a city of seventy thousand that was more than half Jewish, including many survivors of the Holocaust. Jewish organizations were divided about whether to adhere to the ACLU’s position, calling for supporting First Amendment speech principles and permitting the Nazis to march. The national governing board of the American Jewish Congress supported the march in Skokie, so long as the Nazis were not allowed to wear their uniforms and swastikas—the Congress viewed those items as equivalent to illegal “fighting words,” which would incite violence. The ADL and American Jewish Committee opposed the march outright, saying it constituted “menticide,” defined as “the deliberate infliction of mental and emotional distress.”

In Goldman v. Weinberger (1986), the Supreme Court rejected the free exercise challenge of an air force regulation forbidding the wearing of headgear indoors, in this case a yarmulke, the Jewish skullcap worn by Orthodox Jews. All three major Jewish organizations supported the free exercise challenge in amicus briefs. Although the Court ruled against Goldman, Congress later adopted legislation to protect such rights.

Mothers wait to pick up their children from a Hasidic kindergarten in Kiryas Joel, New York, in 2017. The village’s schools have been involved in the Supreme Court case Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet (1994). New York designated the village as a separate school district, but the Court ruled the district was unconstitutional because it included only Hasidic Jews. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

In Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet (1994), the state of New York designated Kiryas Joel, a village of Orthodox Jews, as a separate school district for purposes of providing education for their handicapped children; most of their children attended private religious schools. The Court ruled, however, that the law violated the establishment clause of the Constitution, because the district followed the village boundary line, which excluded all but practitioners of one religion.

This article was originally published in 2009. Ronald Kahn is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Politics at Oberlin College.