John Marshall (1755–1835), the fourth chief justice of the United States, served on the Supreme Court for 34 years. He is the longest serving chief justice and one of the most honored members in the court's history.

During his tenure (1801–1835), the Supreme Court vastly expanded the role of the national government at the expense of states’ rights advocates and broadly interpreted the legislative, executive, and judicial powers that the founders had enumerated in the Constitution.

Consistent with what it believed to be the language and the original intention of the Founders, the Supreme Court under Marshall’s leadership limited the reach of the First Amendment (and other provisions of the Bill of Rights) to actions of the national government. However, by establishing the role of the court as a co-equal branch of government, Marshall laid the groundwork for this institution to protect First Amendment rights in the future, after they were also applied to the states through the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Marshall was part of early American government

Born in Germantown, Virginia, to Thomas and Mary Marshall, John Marshall was one of 15 children. He was largely educated by his father at home. He briefly attended a series of law lectures at the College of William and Mary and passed the Virginia bar in 1780. This brief period of instruction reinforced the knowledge he had gained earlier in life through reading books and interacting with political leaders.

As a soldier in the American Revolution, Marshall worked extensively with George Washington and held the rank of captain when he left the Continental Army in 1781. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates at various times between 1782 and 1796 and was a recorder for the Richmond City Hustings Court from 1785 to 1788.

He worked with James Madison and other delegates at the Virginia Ratifying Convention in 1788 in support of the new Constitution. Marshall was among the more prominent members of the Federalist Party who opposed the adoption of the Sedition Act of 1798, which other members of his party supported. He also served as a minister to France (1797–1798), as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1799–1800), and as President John Adams’s secretary of state (1800–1801).

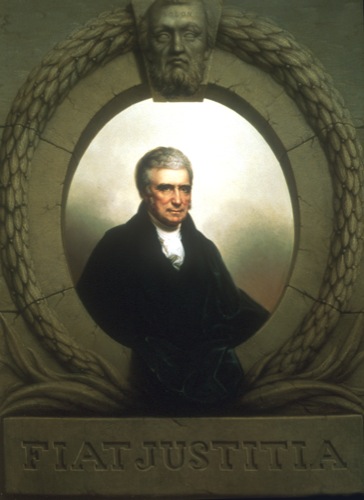

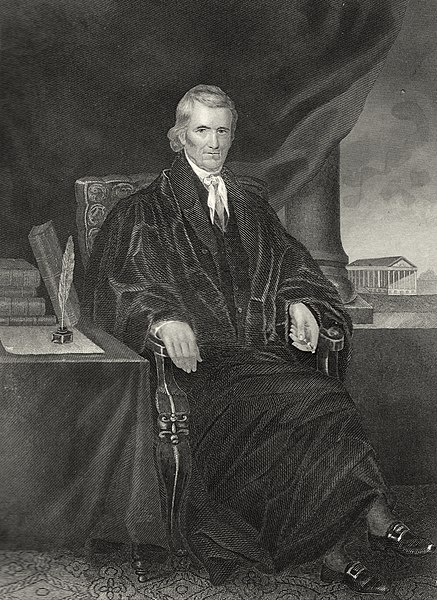

Chief Justice John Marshall projected a sense of power and stature in leading the high court that had been absent until his tenure. He strengthened the court’s position as coequal with the legislative and executive branches of government and established the court’s power of judicial review in the political system. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, Artist: Alonzo Chappel, public domain)

Marshall projected a sense of power over the Court

Adams appointed Marshall as chief justice of the United States in 1801 after Oliver Ellsworth resigned and John Jay declined reappointment to the position. As chief justice, Marshall projected a sense of power and stature in leading the high court that had been absent until then. He wrote many of the court’s decisions during his tenure as chief justice. The justices lodged together during court sessions, and Marshall encouraged fellow justices to refrain from writing separate opinions from the decision of the court.

Marshall strengthened court's power, established judicial review

Marshall’s ingenious legal interpretations had two effects. They strengthened the court’s position as a coequal with the legislative and executive branches of government, and they established the court’s power of judicial review in the political system.

In a landmark case, Marbury v. Madison (1803), Marshall ruled that acts of Congress can be reviewed and struck down if the court deems them to be unconstitutional. This power of judicial review, which the court had previously exercised in upholding federal laws, allowed Marshall to substantiate the court’s power by ruling that Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was void and violated Article 3 of the Constitution. Without this power, the provisions within the First Amendment and elsewhere in the Bill of Rights would not have had nearly the impact they have had in American history.

Marshall reinforced federal power over the states

Marshall’s legal skill further reinforced the national government’s power over the states. The Supreme Court’s decision in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), upholding the constitutionality of the national bank, broadly interpreted the “necessary and proper” clause of Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution. Marshall believed this clause provided the basis for additional “implied powers” to belong to Congress, and he did not believe that states had the power to frustrate such powers by taxing federal institutions.

When Marshall was chief justice, the First Amendment and other provisions of the Bill of Rights were understood to limit only the national government. Marshall affirmed this understanding in Barron v. Baltimore (1833), a case involving the takings clause of the Fifth Amendment, where he argued that the purpose of the Bill of Rights had been to limit the national government rather than the states. The 14th Amendment and the doctrine of selective incorporation have extended the vast majority of the provisions in the Bill of Rights, including all provisions of the First Amendment, to state and local governments.

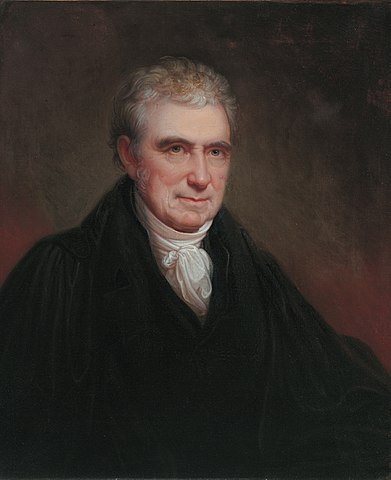

Chief Justice John Marshall reinforced the national government’s power over the states and introduced the concept of “implied powers” in the Constitution. When Marshall was chief justice, the First Amendment and other provisions of the Bill of Rights were understood to limit only the national government. However, the 14th Amendment and the doctrine of selective incorporation have extended the vast majority of the provisions in the Bill of Rights, including all provisions of the First Amendment, to state and local governments. (Image via Viriginia Museum of Fine Arts, Artist: Rembrandt Peale, 1834, public domain)

Marshall Court set many precedents

The Marshall Court set precedents for numerous other issues, while at the same time maintaining this dual theme of enhancing the court’s position and reinforcing national supremacy. Several cases dealt with the commerce clause in Article 1 of the Constitution, which vests all powers to regulate commerce in Congress.

For instance, the Fletcher v. Peck (1810) decision was a blow against states’ rights advocates, while at the same time it established the precedent for protecting individual property rights and contracts, which were one of his major concerns. Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819) reaffirmed the Fletcher decision by ruling that the Supreme Court could strike down state laws, but it focused on those specifically related to states’ regulation of corporations. In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), the court bolstered the commerce clause by prohibiting states from passing any laws that might interfere with the transportation of goods across state lines.

One of Marshall’s most notable commentaries comes from Marbury v. Madison (1803): ”The government of the United States has been emphatically termed a government of laws, and not of men. It will certainly cease to deserve this high appellation, if the laws furnish no remedy for the violation of a vested legal right.”

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in February 2024 by John R. Vile, the dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. Daniel Baracskay teaches in the public administration program at Valdosta State University.