The Supreme Court in Jenness v. Fortson, 403 U.S. 431 (1971), upheld a Georgia law requiring minor-party candidates to obtain the signatures of 5 percent of eligible voters on their nominating petitions. The Court held that the law did not abridge First Amendment rights of free speech and association because there were no restrictions on which voters could sign the petitions, and write-in votes were freely allowed.

Georgia required minor parties to file petitions for ballot access

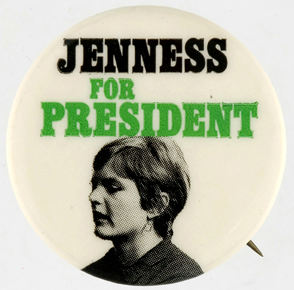

The Socialist Workers Party (SWP) nominated Linda Jenness as its candidate for governor of Georgia in 1970. At the time, Georgia required parties that had not received at least 20 percent of the vote in the previous presidential or gubernatorial election to file petitions to place their candidates on the ballot. Each petition had to be signed by at least 5 percent of the number of voters eligible in the previous election for the office. The party had 180 days to circulate the petitions, which were due on the day the major parties held their primaries.

Before the petition deadline, the SWP filed suit against the Georgia law, and a three-judge district court denied relief to the party. On appeal, the Supreme Court affirmed.

Supreme Court upheld petition requirement

Writing for the Court, Justice Potter Stewart compared the Georgia law with the Ohio laws struck down in Williams v. Rhodes (1968), which had intended to make the Democratic and Republican Parties “a complete monopoly” by forbidding independent candidates, barring write-in votes, and requiring minor parties to obtain the signatures of 15 percent of the number of voters in the previous gubernatorial election by early February of the election year and thereafter hold a primary election.

The Court held that the Georgia law was much less strict on minor parties because of the smaller number of petition signatures, the later deadline for the petitions, absence of a primary requirement, and acceptance of write-in votes. The Court noted that by using petitions, George C. Wallace (of the American Independent Party) had been able to qualify in Georgia as a third-party presidential candidate in 1968, and Howard “Bo” Callaway (of the Republican Party) had received a plurality of the vote for governor in 1966 after qualifying by petition.

Justices Hugo L. Black and John Marshall Harlan II concurred without writing opinions.

This article was originally published in 2009. Edward Still has practiced in Alabama and Washington, D.C., since 1971. He has brought numerous First Amendment, due process, and equal protection suits for a variety of people: public employees, playwrights, religious and political minorities, and even truckers over state regulation of bumper stickers.