In Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518 (1972), the Supreme Court limited the scope of the “fighting words” exception to the First Amendment and enhanced the long-term development of the overbreadth doctrine — the notion that statutes and regulations must be sufficiently precise in order to avoid regulating protected as well as unprotected speech.

Wilson used “fighting words” against arresting officers

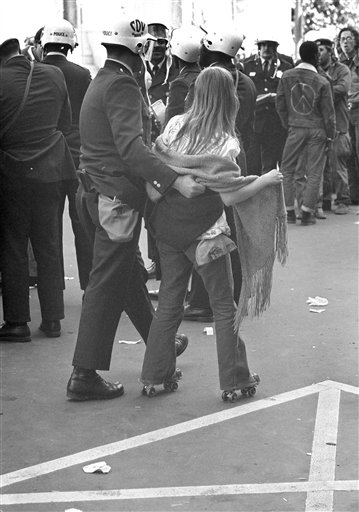

When Johnny C. Wilson, an anti-war activist, was taken into custody for interfering with military recruitment, he threatened to kill arresting officers. He was charged under a Georgia statute that outlawed “opprobrious words or abusive language tending to cause a breach of the peace.”

The Supreme Court first identified fighting words as a categorical exception to the First Amendment in Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942). A unanimous Court held that words that “by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace” constituted unprotected expression.

Court concluded Georgia law was overbroad

Writing for the majority in Gooding, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. invalidated the Georgia statute, interpreting Chaplinsky to apply only to language that had “a direct tendency to cause acts of violence by the person to whom, individually, the remark is addressed.” The Court analyzed the history of Georgia’s application of the statute and concluded that it had been invoked repeatedly to punish the use of communications that were “not ‘fighting words’ as Chaplinsky defines them.” Thus, the Court concluded that the statute was overbroad because it was “susceptible of application to protected expression.” The Court reached this conclusion despite the fact that Wilson’s words would likely have been punishable under a more narrowly drawn statute drafted in conformance to the requirements of Chaplinsky.

The Court’s decision in effect limited the application of the “fighting words” exception. When classifying expression as fighting words, courts would look at a communication’s tendency to produce an immediate and violent reaction rather than the offensiveness of the language used.

The Court’s decision also apparently induced, albeit unintentionally, a dramatic shift in interpretation of the overbreadth doctrine. Chief Justice Warren Earl Burger and Justice Harry A. Blackmun wrote scathing dissents, chastising the Court for declaring unconstitutional a statute that “has little potential for application outside the realm of ‘fighting words.’”

One year later, in Broadrick v. Oklahoma (1973), the Court substantially limited the scope of its authority to overturn statutes, requiring that in future cases “the overbreadth of the statute must not only be real but substantial as well” to justify invalidation. The relative infrequency of contemporary applications of the overbreadth doctrine is thus indirectly but clearly traceable to the majority opinion in Gooding.

This article was originally published in 2009. Richard A. “Tony” Parker is an Emeritus Professor of Speech Communication at Northern Arizona University. He is the editor of Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives On Landmark Supreme Court Decisions which received the Franklyn S. Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression from the National Communication Association in 1994.