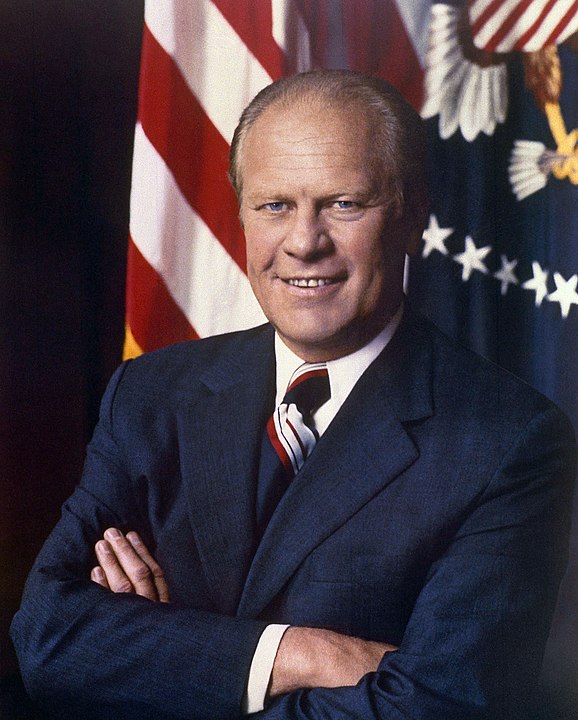

Gerald R. Ford (1913-2006) is the only individual who has served as U.S. president without being elected to that office as either president or vice-president.

Born in Omaha, Nebraska, and raised in Grand Rapids Michigan, Ford earned his bachelor’s degree at the University of Michigan, where he played on the school’s football team. He earned a law degree at Yale University and served in the U.S. Naval Reserve during World War II.

Ford served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Michigan and became the House minority leader in 1965. After Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned in 1973, President Richard Nixon selected Ford in part because he thought he could be confirmed under the terms of the 25th Amendment, which had been ratified in 1967 and never before had been used to fill such a vacancy.

Ford accepted office, humbly observing, in a play on his last name in remarks that he made on Dec. 6, 1973, that “I am a Ford, not a Lincoln. My addresses will never be as eloquent as Mr. Lincoln’s. But I will do my very best to equal his brevity and his plain speaking.”

Ford became president on Aug. 9, 1974, after President Nixon resigned when it appeared that he would be impeached and convicted of crimes in connection with the coverup of the illegal break-in at the Democratic National Headquarters at the Watergate complex. Ford chose Nelson Rockefeller as his vice president under the terms of the 25th Amendment, although he would unsuccessfully run with Robert Dole as his vice president in the 1980 presidential election that brought Jimmy Carter into office.

Ford brings stability after Nixon scandal

Ford brought stability and integrity back to a presidency that had been wracked by scandal, but he shocked the nation and lost considerable public support after issuing a pardon to former President Nixon for any offenses he may have committed as president.

Ford, who testified before Congress about the pardon, feared that continuing investigations would divert the nation’s attention from pressing problems. He also believed that Nixon’s acceptance of this pardon constituted an admission of guilt and hoped that the pardon would bring national healing. The pardon definitely affected Ford’s own popularity and likely was a central cause in his failure to win the next presidential race.

Not long after he became president, Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, fell to North Vietnamese invaders, making the U.S. look weak. This appears to be one reason that Ford later took such decisive military action in recovering the Mayaguez ship after it was captured by communist Cambodian rebels.

The year 1976 further brought back a level of national pride in fundamental rights as the nation celebrated the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

The period was inflationary and some of Ford’s responses, as in handing out WIN (Whip Inflation Now) pins, were ridiculed as largely ineffectual.

Court addresses campaign regulations and First Amendment

In a speech that Ford delivered to a joint session of Congress on Aug. 12, 1974, he observed that “I believe in the first amendment and the absolute necessity of a free press.”

Ford was religious but preferred not to mix religion and politics. He did favor governmental aid to private religious schools (Veenstra 2015, 15).

Facing Democrat majorities in Congress, Ford frequently exercised the veto power, and was overridden more than most of his predecessors. One such override occurred when Congress overrode his veto of amendments to the Freedom of Information Act (1966), which opened access to materials that Ford thought should be classified.

Largely in reaction to abuses by the Nixon Administration, in 1974, Congress adopted amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, in which it limited campaign contributions and imposed spending limits and disclosure requirements.

In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Supreme Court largely upheld campaign contribution limits (exempting, however, personal money that candidates spent on their own campaigns) and disclosure requirements, while striking down spending limits as interfering with First Amendment rights of expression.

Court rules on zoning laws to regulate adult businesses

In Hudgens v. National Labor Relations Board (1976), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that private shopping malls were not required to allow protestors to exercise their First Amendment rights there.

In Young v. American Mini Theatres (1976), the court further allowed local governments to use zoning laws to regulate adult businesses to regulate negative side-effects of such establishments.

Ford became the catalyst for a lawsuit after he left office when Harper and Row publishers successfully won a suit against the Nation magazine when one of its writers obtained a pre-release copy of Ford’s autobiography, "A Time to Heal" and published a 300-word excerpt. The Supreme Court decided in Harper and Row v. Nation Enterprises (1985) that the use by the magazine was a copyright infringement rather than fair use.

Ford appoints John Paul Stevens to Supreme Court

Ford had the opportunity to nominate only one Supreme Court Justice. His successful nomination of John Paul Stevens to replace retiring Justice William O. Douglas (whom Ford had once attempted to impeach) was one of the most non-ideological appointments to that body in recent years.

Unlike most of his fellow contemporary presidents, Ford highlighted competence and professionalism over ideological concerns, and Stevens proved to be harder to categorize as either liberal or conservative on First Amendment and other issues (O’Brien 1991).

Ford later introduced Judge Robert Bork, a much more polarizing figure, to the Senate Judiciary Committee when Ronald Reagan nominated him to the Supreme Court. The Senate rejected Bork’s nomination in highly polarized hearings.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Jan. 16, 2024.