The Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 (1965), that the prior restraint carried out under Maryland’s motion picture censorship statute since 1916 unduly restricted the First Amendment rights of film distributors and exhibitors. The reverse burden of proof that government censorship laws placed on film distributors created unacceptable delays that might have a chilling effect on speech.

Film censorship statutes were based on prior restraint

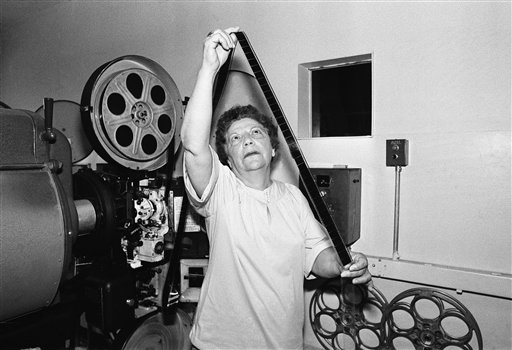

Film censorship statutes that came and went between 1907 and 1981 in seven states and dozens of municipalities were based on prior restraint — that is, they required that movies be examined before they could be shown. Licenses were denied to movies found to be obscene, sacrilegious, indecent, inhuman, immoral, or likely to incite criminal activity. Distributors refused licenses had only one recourse: to bring suit against the censors.

Court allowed prior restraint of films

In the first challenge to movie censorship to reach the Supreme Court — Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio (1915) — the Court upheld the authority of government to deny the screening of any film not approved by a board of censors. The Court based its reasoning on the belief that films carried an inherent “capacity for evil.”

Thirty-seven years later, in Burstyn v. Wilson (1952), the Court overturned Mutual Film and brought movies under the free speech protection of the First Amendment. Yet the Court did allow prior restraint of movies to continue under “narrowly drawn” statutes. Over the next seven years, film censors lost six more cases. Then, in 1961 in Times Film Co. v. City of Chicago, the Court reversed direction, finding that film censorship did not violate the First Amendment.

Freedman challenged Maryland’s film censorship

When Baltimore theater owner Ronald Freedman and the Times Film Co. decided to test the constitutionality of Maryland’s prior restraint in 1962, only Kansas, New York, Maryland, Virginia, and a few cities continued to censor films. To force the issue in Maryland, Freedman refused to submit to censors Revenge at Daybreak, an unobjectionable French film about the 1916 Irish revolution. Attorneys Richard Whiteford and Felix Bilgrey argued for Freedman that Maryland’s licensing procedure restrained not only obscenity, but also expression that the First Amendment protected. They argued as well that the Maryland statute was overbroad, imposed a tax on the right of communication, and allowed indefinite delay. (It took Freedman two years to reach the Supreme Court.)

Court shifted burden of proof to censors and required ‘prompt’ judicial review

In the opinion for the Court, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. tried to balance the right of free expression against the state’s power to protect public morality and the Court’s belief that movies were different from other means of communication.

In doing so, he established two procedural safeguards. First, the burden of proof shifted to the censors who had to either quickly issue a license or go to court to demonstrate why a film was not protected by the First Amendment. Second, a censorship statute had to provide for “prompt” judicial review.

Freedman factors play a role in First Amendment jurisprudence

Today, the so-called Freedman factors still play a significant role in First Amendment jurisprudence. Although the Court had not declared prior restraint of movies unconstitutional, the new restrictions prompted the remaining censoring states, except one, to cease censorship within two years.

Maryland redrafted its statute to conform to the Freedman guidelines and continued censoring movies until 1981.

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. Laura Wittern-Keller is a U.S. history professor at the University at Albany (SUNY). She has written two books on movie censorship and the First Amendment: Freedom of the Screen: Legal Challenges to State Film Censorship (University of Kentucky Press, 2008) and The Miracle Case: Film Censorship and the Supreme Court (University of Kansas Press, 2008).