In Epperson v. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968), the Supreme Court unanimously struck down an Arkansas law that criminalized the teaching of evolution in public schools. The Court found that the law had the unconstitutional purpose and effect of advancing religious beliefs, contrary to the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

Arkansas law outlawed teaching evolution

Under the Arkansas statute, enacted in 1928 and based on the Tennessee statute at issue in the infamous Scopes monkey trial, a teacher in a public school or university could not “teach the theory or doctrine that mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals, [or] . . . adopt or use in any such institution a textbook that teaches” the theory of evolution.

Epperson challenged law for vagueness

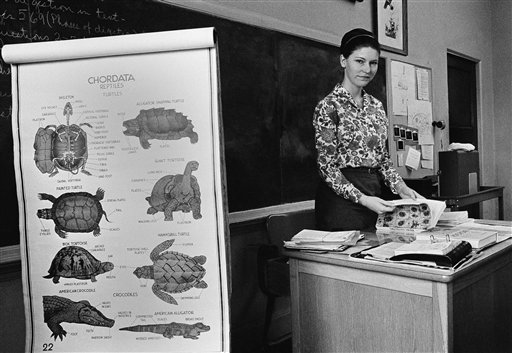

In 1965 the Little Rock, Ark., school district adopted a new biology textbook that included the theory of evolution. Faced with the possibility that teaching from this book would constitute a criminal offense (the law had never been enforced against a teacher but remained on the books), a new biology teacher, Susan Epperson, sought a declaratory action, which could ensure that she could teach the text without being prosecuted.

After losing her case before the Supreme Court of Arkansas, Epperson appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Her initial argument was that the statute was void for vagueness. Although this argument appealed to two concurring justices, the others disagreed — at oral argument, counsel for the state of Arkansas had stated, “just to teach that there was such a theory [of evolution]” would violate the statute.

Court said law violated the First Amendment

The majority, led by Justice Abe Fortas, focused its analysis on the establishment clause. It relied on the general principle that government “may not be hostile to any religion or to the advocacy of nonreligion; and it may not aid, foster, or promote one religion or religious theory against another or even against the militant opposite.”

The Court then extracted the legal test from Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) and found that the law had both the unconstitutional purpose and effect of advancing religious beliefs.

Decision marked the end of anti-evolution stautes

The decision in Epperson marked the end of the first generation of so-called anti-evolution statutes. In response to Epperson, many states enacted statutes requiring a balanced treatment of evolution and creationism (or creation science), which later were held unconstitutional in McLean v. Arkansas (E.D. Ark. 1981) and Edwards v. Aguillard (1987).

This article was originally published in 2009. Kristine Bowman is a Professor of Law at Michigan State University.