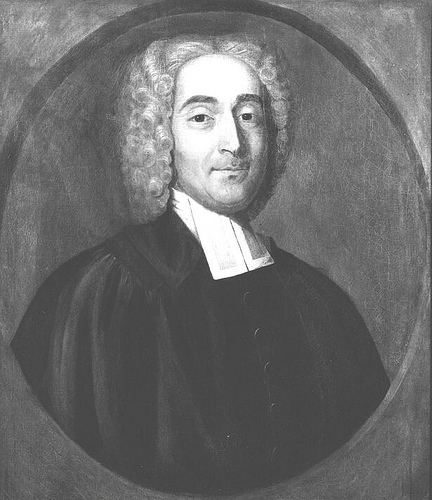

Elisha Williams (1694-1755) — a Harvard graduate who served at various times as a professor and rector at Yale University, where he tutored Jonathan Edwards; as a pastor; and as a member of the Connecticut General Assembly — is best known as the author of The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants: A Reasonable Plea for the Liberty of Conscience and the Right of Private Judgment in Matters of Religion (1744).

Connecticut law barred ministers from delivering sermons outside their own parishes

He wrote the pamphlet in the form of an extended letter under the name “Philalethes” to oppose a 1742 Connecticut law known as the Act for Regulating Abuses and Correcting Disorders in Ecclesiastical Affairs, which had been prompted by opposition from established preachers to revivalists of the Great Awakening. The act prohibited ministers from delivering sermons outside their own parishes without invitations from established clergy, and Williams believed it violated the rights of Englishmen as outlined in the Toleration Act of 1688 as well as natural rights.

Williams’ views on religious rights inspired by John Locke

Williams drew many of his ideas on the role of government and about rights from John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government. He argued that men are born free and equal, that they form government for the limited purposes of securing their lives, liberties, and property, and that citizens retain their rights to judge religious matters for themselves.

Williams drew four major conclusions.

- First: “the civil authority hath no power to make or ordain articles of faith, creeds, forms of worship or church government.”

- Second: “the civil authority have no power to establish any religion (i.e., any professions of faith, modes of worship, or church government) of a human form and composition, as a rule binding to Christians; much less may they do this on any penalties whatsoever.” To grant the government such power was to vest fallible institutions with improper power. Like Locke, Williams was strongly anti-Catholic, pointing to the ills that had followed when Catholic states sought to enforce such uniformity or when the Anglicans had tried to do so in England. He also denied that “unity, or uniformity in religion” was “necessary to the peace of a civil state.” Rather, Christians should treat one another in accord with the Golden Rule. Indeed, Williams believed that “legal establishments have a direct contrary tendency to the peace of a Christian state” because they encroach on Christian liberty.

- Third: civil authority should “protect all their subjects in the enjoyment of this right of private judgment in matters of religion, and the liberty of worshipping GOD according to their consciences.”

- Fourth: “every Christian has [the] right to determine for himself what church to join himself to; and every church has [the] right to judge in what manner GOD is to be worshipped by them, and what form of discipline ought to be observed by them, and the right also of electing their own officers.”

Prior to the First Amendment, Williams observed importance of religious liberty

Williams ended his letter by showing point by point how the newly enacted Connecticut law violated these precepts. He observed that religious liberty was “so precious a jewel” that it “is always to be watched with a careful eye: for no people are likely to enjoy liberty long, that are not zealous to preserve it.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.