From 1941 through 1973, with a short interruption in the late 1940s, young men at age 18 were required by law to register with their local draft boards. Each was classified according to his fitness for service and issued a draft card noting his name, age, and draft status.

Draft card destruction viewed as symbolic protest against Vietnam War

Possession of the card proved that the card bearer was compliant with the Selective Service System and had not tried to evade classification for military service.

Draft operations ran relatively smoothly before and during World War II and again during the Korean War and the 1950s. By the mid-1960s, as the United States drafted more troops for the Vietnam War and opposition to the war heightened, some men viewed the public destruction of their draft cards as an effective form of symbolic protest against both the war and the draft system that supported it.

Draft-card burning became one of the most iconic forms of protest during the war. It was a gesture made by young men who wished to buck the system but were not comfortable with more extreme measures such as going to Canada, participating in riots, or destroying induction centers. The symbolic act had legal implications, however.

Burning draft cards was a criminal offense

Burning draft cards was ipso facto illegal because all eligible men were legally required to carry their draft cards with them at all times.

Furthermore, after Congress adopted the Draft Card Mutilation Act of 1965 to promote the efficient operation of the Selective Service System and preempt venues of resistance, it became a criminal offense knowingly to destroy or mutilate one’s draft card.

The law codified previous inferences that men needed to carry and maintain their cards in a presentable manner. In passing the measure, Congress curtailed the scope of symbolic speech in the name of good government.

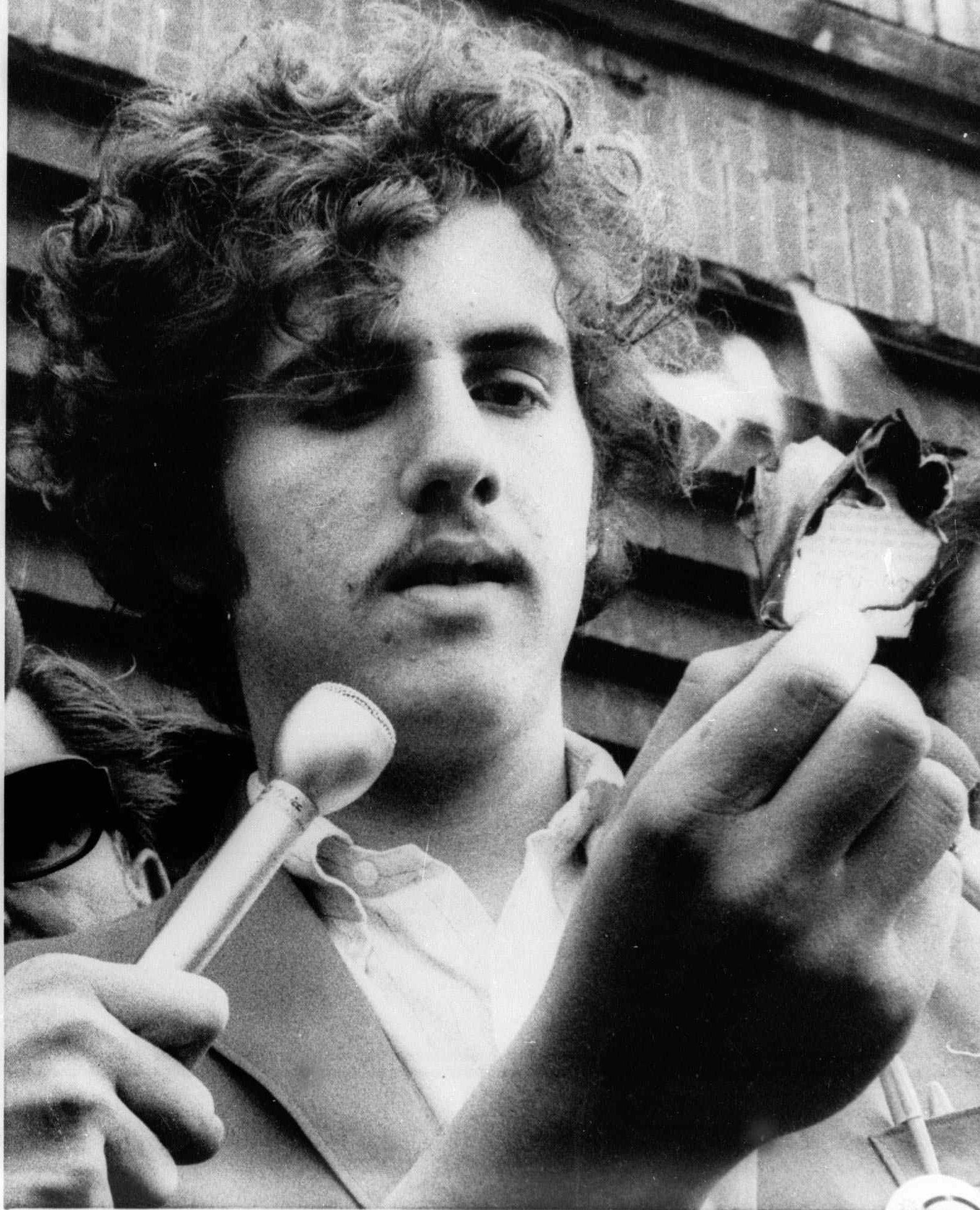

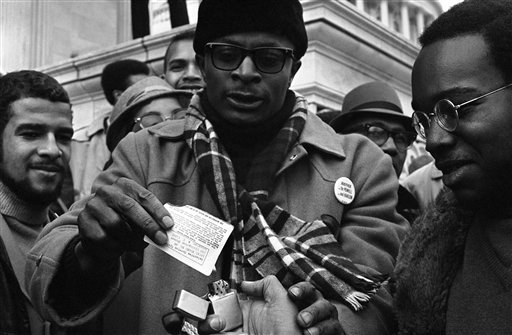

The Supreme Court rejected a First Amendment challenge to a law that prohibited destroying draft cards during the Vietnam War. In this photo, unidentified men hold a cigarette lighter under a draft classification card on the steps of the Capitol in Washington in 1967. (AP Photo/Charles Tasnadi, used with permission from the Associated Press)

O’Brien thought law against draft card mutilation violated the First Amendment

In United States v. O’Brien (1968), the Supreme Court considered the government’s right to require possession and punish mutilation of draft cards against individuals’ rights to engage in symbolic speech acts under the protection of the First Amendment.

David Paul O’Brien opposed the Vietnam War and was frustrated by what he deemed an unconstitutional restriction of symbolic speech as protected by the First Amendment, so he burned his draft card publicly, on the steps of a Boston courthouse. Arrested and convicted of draft-card mutilation, he appealed his case until it reached the Supreme Court.

Court upheld law as a means of protecting the nation

In a 7-1 decision written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Court upheld O’Brien’s conviction and upheld the law as a means of protecting the nation that incidentally affected freedom of speech.

In the decision, the Court established a four-part test that it continues to apply in cases of symbolic speech. This test requires the government to show that it has the power to enact such a measure, that it has established an important governmental interest, that the measure’s purpose is unrelated to speech, and that it has imposed the least restrictions necessary to accomplish the objective.

This article was originally published in 2009. Jason Friedman holds a PhD in American history with a focus on 1970s politics. He has published and presented internationally about the Vietnam War draft. Currently, he teaches history and political science at The Winchendon School in Massachusetts.