Door-to-door solicitation by political parties, candidates for public office, religious groups, charities, and purely commercial enterprises can lead to clashes between First Amendment free expression and homeowners’ privacy rights.

First Amendment rights can conflict with privacy rights in solicitation cases

Via the 14th Amendment, the courts have applied to states and localities First Amendment provisions protecting the free exercise of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of association, freedom of petition, and freedom of peaceable assembly.

These rights sometimes come into conflict with localities’ legitimate interests in protecting their citizens from fraud and violence and preserving their privacy in their homes. These divergent interests are reflected in the tensions among cases that have addressed these issues.

In Breard v. Alexandria (1951), the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a Green River ordinance prohibiting door-to-door commercial solicitations other than those invited by residents. The precedent established by the case is not clear, however, because the Court has extended increased protection to commercial speech in more recent decisions.

In Watchtower Bible and Tract Society v. Village of Stratton (2002), the Supreme Court struck down a law in Stratton, Ohio, that required anyone going door to door to register with authorities and carry a permit. In this photo, a sign informs motorists of the solicitation guidelines in Stratton. (AP Photo/Gary Tramontina, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court often upholds religious solicitation

Moreover, in many instances the Court has upheld the right of individuals to engage in door-to-door solicitations for noncommercial causes, especially those of a religious nature.

In Lovell v. City of Griffin (1938) and Schneider v. State (1939), the Court struck down ordinances requiring Jehovah’s Witnesses and others to obtain the city manager’s permission prior to engaging in door-to-door solicitations.

It reiterated these rulings in Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940) and Largent v. Texas (1943). In Martin v. City of Struthers (1943), the Court overturned a blanket prohibition on the door-to-door distribution of literature.

The decision in Murdock v. Pennsylvania (1943) invalidated a license tax required to solicit door-to-door, thus overturning a recent contrary decision in Jones v. City of Opelika (1942). By contrast, in Prince v. Massachusetts (1944), the Court upheld child labor regulations that applied to door-to-door solicitations, even those involving religion.

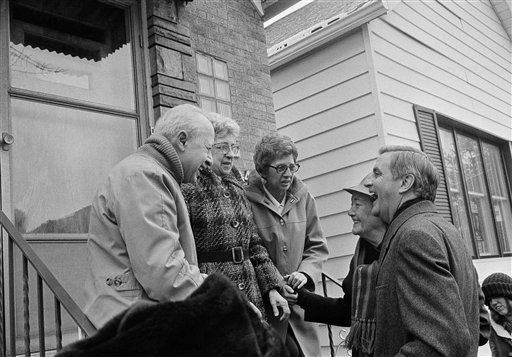

The Supreme Court has often affirmed the reasonableness of “time, place, and manner” restrictions in the door-to-door context. In this photo, Vice President Walter Mondale, right, does some door-to-door campaigning in Chicago’s in 1980. (AP Photo/Charles E. Knoblock, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Recent court cases have looked at vagueness of solicitation statutes

More recent cases have repeated many of the same themes.

In Staub v. City of Baxley (1958), the Court reaffirmed that a state could not vest discretion in local officials to determine who would or would not be permitted to make door-to-door solicitations based on officials’ judgments of the public interest.

Similarly, in Hynes v. Mayor of Oradell (1976) the Court decided that a law requiring door-to-door solicitors to notify town officials of their activities in writing was too vague. It voided a similar registration requirement in Watchtower Bible and Tract Society v. Village of Stratton (2002).

Court has affirmed ‘time, place, and manner’ restrictions

The Supreme Court has often affirmed the reasonableness of “time, place, and manner” restrictions on speech in the door-to-door context. It thus seems that courts would be likely to uphold laws designed to limit solicitations to daylight hours or laws affirming the rights of residents to post signs indicating that they do not wish to be disturbed by solicitors.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.