In De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353 (1937), the Supreme Court ruled that state governments may not violate the constitutional right of peaceable assembly. The decision contributed to the development of “symbolic speech” and “speech plus” categories, concepts relating to speech combined with conduct or action.

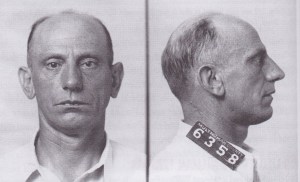

De Jonge arrested for talking about communist ideas

On July 27, 1934, the Portland police arrested Communist Party member Dirk De Jonge and three other speakers at a meeting of 150–300 people who were protesting police brutality in recent confrontations with striking union longshoremen. While De Jonge appealed to some communist ideas during his speech, neither he nor the other speakers advocated violence.

In the unanimous decision, the Court ruled against Oregon’s 1930 Criminal Syndicalism Act, as amended in 1933, which made it a felony for “any person to become a member of any society or assemblage of persons which teaches or advocates the doctrine of criminal syndicalism.”

The statute, which was intended to suppress communism, defined criminal syndicalism as the doctrine that “advocates crime, physical violence, sabotage, or any unlawful acts or methods as a means of accomplishing or effecting industrial or political change or revolution.”

Court had previously distinguished between advocacy and incitement

The De Jonge ruling rested on previous cases, most notably Gitlow v. New York (1925) and Whitney v. California (1927).

In Gitlow, the Court found that a state may restrict expressions calling for the violent overthrow of government if the expressions in question possess a “tendency” to incite such activity.

Important in that case was that the Court’s opinion defended the concept that the 14th Amendment’s due-process clause protects First Amendment rights — in this case free speech and free press — at the state level.

Further, although the Court had upheld a state law against syndicalism in Whitney, Justice Louis D. Brandeis’s concurring opinion provided a compelling defense of free speech and made the distinction between advocacy and incitement.

Supreme Court struck down criminal syndicalism law

Portland attorney and American Civil Liberties Union member Gus J. Solomon was instrumental in placing the De Jonge case in the context of these earlier First Amendment decisions. He believed that winning the case would be a victory for the constitutional guarantee of due process, and he asked New York attorney Osmond K. Fraenkel to defend De Jonge.

Writing on behalf of the unanimous Court (8-0, with Justice Harlan Fiske Stone absent), Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes applied the right to assemble peacefully to the states and affirmed the protection of free speech from state governments.

“The holding of meetings for peaceable political action cannot be proscribed,” he wrote.

Furthermore, Hughes continued, a state could not interfere with a group’s right to gather and discuss political issues; such laws were “repugnant to the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Gary E. Bugh is Professor of Political Science, Chair of the Political Science Department, and University Pre-Law Advisor at Texas A&M University-Texarkana. He teaches Political Theory, American Political Theory, Constitutional Law, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, Political Parties and Elections, and the Presidency. His publications include Electoral College Reform: Challenges and Possibilities (Routledge, 2016).