In Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 481 (1819), the Supreme Court ruled that the state of New Hampshire had violated the contract clause in its attempt to install a new board of trustees for Dartmouth College. This case also signaled the disestablishment of church and state in New Hampshire.

New Hampshire attempted to convert a private college into a public university

Dartmouth College was founded by Congregational minister Eleazar Wheelock, who had received in 1769 a charter from the English Crown that granted authority to a board of trustees created by Wheelock. After the American Revolution, the institution sometimes received state funds and was largely controlled by Federalist trustees, who continued to emphasize the college’s original religious mission. John Wheelock succeeded his father as president in 1779; the trustees fired him in 1816 because of his autocratic manner.

In 1816 Democratic-Republicans in the state legislature amended the college’s charter and attempted to convert the school into a secular institution, Dartmouth University, more compatible with their party’s objectives. They created a new board of elected trustees and appointed Wheelock president.

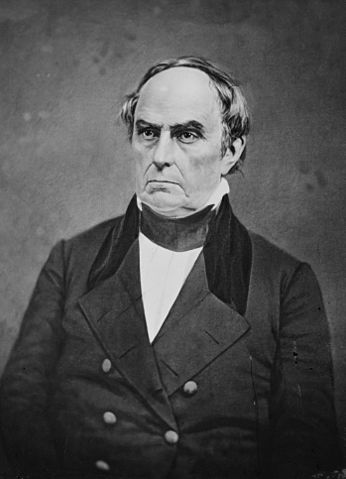

The original trustees continued to operate Dartmouth College and employed Dartmouth alumnus Daniel Webster to represent them in suing William Woodward, the secretary and treasurer of the college who had transferred to the new university, taking with him the college’s charter, records, and seal.

Dartmouth College argued the conversion violated the Constitution

The original trustees argued that the legislature had violated vested rights, the state constitution, and the U.S. Constitution’s contract clause. A state court sided with Woodward, declaring the college a public corporation, which therefore made it subject to state legislation. The Supreme Court reversed in a 5-1 decision.

In the opinion for the Court, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote that by establishing a corporation, Eleazar Wheelock had created “an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of the law.”

He explained that “by these means, a perpetual succession of individuals are capable of acting for the promotion of the particular object, like one immortal being.”

Over the years, individuals had contributed to the college believing their donations would continue to support the institution’s original mission; if governments did not protect such entities, individuals would be less likely to contribute to them in the future.

The charter had not created a “civil institution to be employed in the administration of the government” — which would have permitted continuing governmental control — but rather “a private eleemosynary [charitable] institution.”

The Court ruled New Hampshire violated Dartmouth’s charter

Marshall concluded that Dartmouth’s charter constituted a contract and that New Hampshire had violated this contract in attempting to replace the original trustees. Much as Justice Joseph Story had observed in Terrett v. Taylor (1815), which related to Virginia’s attempt to sell lands owned by the Episcopal Church, Marshall observed that Dartmouth College “is no more a state instrument than a natural person exercising the same powers would be.”

In a separate concurring opinion, Justice Story observed that in creating contracts, states could reserve certain powers for themselves (as they sometimes did after this decision), but that the state of New Hampshire had not done so in this case.

Justice Bushrod Washington also wrote a separate opinion concurring with the collective thoughts of Marshall and Story. Justice Gabriel Duvall dissented without a written opinion.

States could no longer control private entities

Mark McGarvie notes that this opinion must be considered in conjunction with the Court’s decisions in Philadelphia Baptist Association v. Hart’s Executors (1819) and Terrett v. Taylor (1815). McGarvie observes, “After the Dartmouth College decision, government could not rely upon private philanthropic associations to address public perceptions of societal needs. The public-private distinction required states to define their priorities more carefully” (2005: 178).

That is, states could not assume that private entities would take the same approach to issues that they would. McGarvie further observes that New Hampshire did not disestablish its own church until after this decision and that it may thus have assumed it had greater authority over religious entities than it would later have.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.