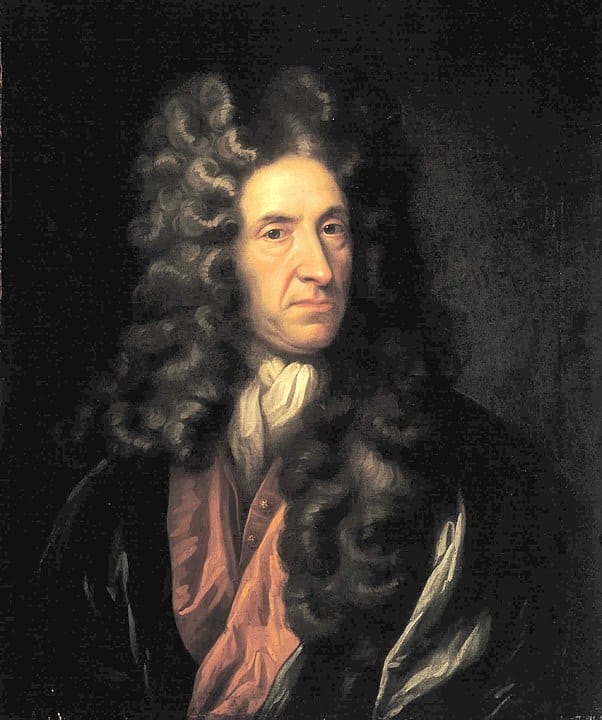

Although it is common to tie early American thinking about church and state to John Locke and other English Whigs, such as John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon who authored “Cato’s Letters,” it is less common to see references to the British novelist Daniel Defoe (1660-1731).

Born in England and educated at a boarding school of a clergyman, Defoe gave up early hopes of being a clergyman to become a merchant and writer. Although his best-known work remains “The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe” and his novel “Moll Flanders,” more than 100 of his 254 published works dealt either with politics or religion (Brinsfield 1975, 107).

In the early 1700s, Defoe became involved in an effort to rid the Carolina colony of a religious test that required members of the colonial legislature to swear membership in the Church of England. Defoe wrote two significant pamphlets against the test, emphasizing religious liberty and the freedom of conscience as individual rights promised in the colony’s charter.

Carolina colonial legislature required Church of England oath

South Carolina was established in 1663 under a constitution drafted by John Locke, who had advocated religious toleration, which the colony had advertised as a way of enticing immigrants. Faced with opposition to a costly attack on St. Augustine and poor relations with Native Americans, and influenced by John Lord Granville, the president of the Carolina Proprietors, and Governor Nathaniel Johnson, the colonial legislature in 1704 adopted an Exclusion Act.

The Exclusion Act required each member of the legislature to provide evidence that he had been administered sacraments by the Church of England over the past year or to take an oath affirming that he was a member of this church. This resulted in the exclusion of the dissenters (as non-Anglicans were called) from this body. It also spurred mob action against those who opposed the law, including the Rev. Edward Marston, an Anglican rector of St. Philip’s Church in Charleston, who opposed the bill.

Protestant dissenters in Carolina launch opposition to Exclusion Act

The dissenters hired Defoe, himself a prominent English dissenter, to draw up pamphlets on behalf of the colonial cause. He drafted “Party Tyranny: Or, An Occasional Bill in Miniature: as now Practiced in Carolina,” as well as a subsequent pamphlet called “The Case of Protestant Dissenters in Carolina.”

At a time when Great Britain relied on an unwritten Constitution, in seeking to make the case for Carolina dissenters, Defoe relied strongly on colonial charters and on promises made in speeches by earlier monarchs to secure rights, much as Americans would later stress the value of written constitutions with provisions such as the First Amendment, to do so.

Defoe based his arguments promises of religious freedom

Defoe’s arguments in both pamphlets were similar and rested clearly on promises made and charters issued promising religious freedom. In his first pamphlet, which was directed to the British Parliament, Defoe observed that the Constitution has specified that the only qualifications for being admitted to any church or Government, was “1. That he believe there is a God, 2. That God is Publickly to be Worshiped” (1705, 8).

It had further provided that “No Person whatsoever, shall Disturb, Molest, or Persecute, another for his Opinion in Religion, or Way of Worship” (8). Defoe had included a petition by the dissenters as well as letters documenting the abuse that the dissenters had suffered.

‘Liberty of conscience’ is a key individual right, Defoe writes

In his second pamphlet, Defoe argued that liberty of conscience was a key right: “And as Liberty is the only Foundation of our Quiet and Satisfaction in this World; so Liberty of Conscience is the only Security that any Government can give us for our safe Passage thro this World to another” (1706, 3; f’s changed to s’s where appropriate). He believed that such liberty allowed “every Man to believe what appears to him to be true, and to act pursuant to his Belief in matters relating to another Life, that don’t disturb the Public Peace” (3). He further argued that “even our Civil Liberty itself become precarious and defeasible, where the Liberty of Mens Consciences has not the strongest Securitys that may be” (4). Just a Thomas Jefferson would later claim that “it does me no injury for my neighbour to say there are twenty gods, or no god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg,” Defoe argued for liberty “in matters, which they can do no body good or hurt besides themselves . . . but in relation to another World” (4).

Recounting the controversy that the law had brought about in Carolina, Defoe argued that the new law “is against Natural Equity, the Christian Religion, the First Principles of the Reformation, and the true interest of every Community” (11). Defoe went on to observe that freedom of conscience had encouraged individuals, including some who had felt oppressed in Britain, to move to the colony. He further questioned the religious commitment of those legislators in Carolina who professed to believe in the Church of England. Defoe observed that the original charter had granted full rights of toleration and that the new act was therefore “a Breach of the express Original Contract between the Proprietors and the People of Carolina” (29). To prove his point, Defoe published his essay along with the Charter granted by King Charles II, the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, and other documents.

Two years later, Carolina’s religious oath test declared illegal

In 1706, the Lords of the Committee of Trade declared the Exclusion Act to be illegal after which Queen Anne voided the law, and Colonel Edward Tynte replaced Governor Johnson.

Professor John W. Brinsfield observes that this “marked the last time in the eighteenth century that a major effort was made to disfranchise a legislative body in an American colony by means of a religious test” (1975, 111).

William Tennent III and others later argued for the complete disestablishment of the Anglican Religion in South Carolina in 1776, and this movement was completed in 1790.

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.