In June 1865, Missouri, whose citizens had been deeply split by the Civil War, adopted a constitution that barred from voting any individuals who were unwilling to take an oath that they had never aided the Confederacy or any of its participants or who had left the state to escape conscription.

They also would be disbarred from certain professions, including the law, the ministry or education.

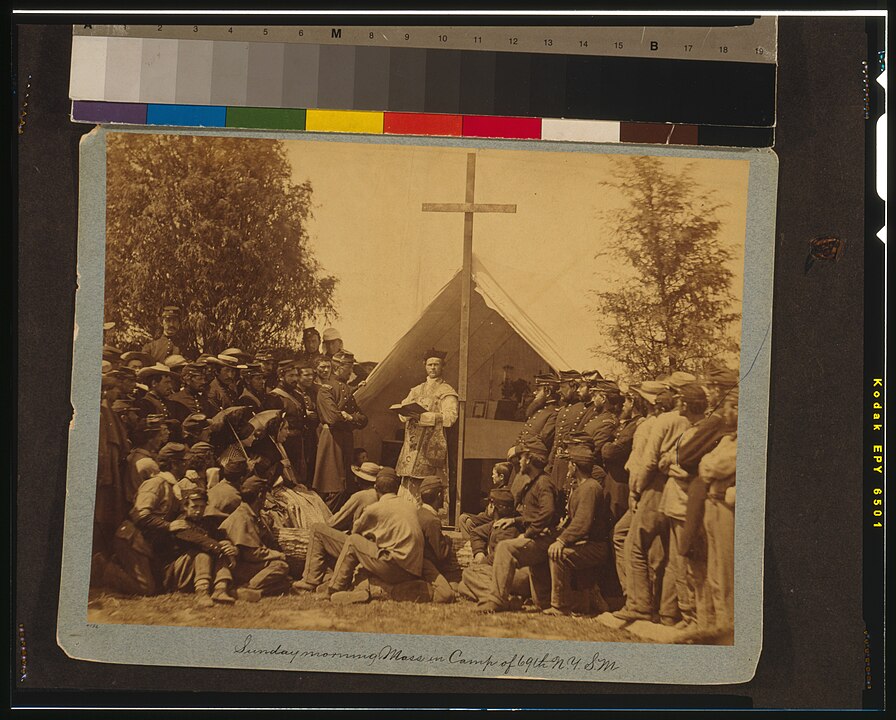

Catholic priest refused to take oath

A Catholic priest who was unwilling to take the oath challenged the provision alleging in Cummings v. Missouri, 71 U.S. 277 (1866) that it violated the prohibitions in Article I, Section 9, of the U.S. Constitution against bills of attainder and ex post facto laws.

Cummings’ attorney argued that “the right or privilege, whichever it may be called, of preaching and teaching as a Christian minister, which he had theretofore enjoyed, and of acting as a professor or teacher in a school or educational institution, was in effect a punishment.”

The state’s attorney denied that such exclusions constituted punishments and observed that although “the rights of conscience are sacred rights,” they differed from “the unrestrained license to corrupt, from the pulpit, the public taste or the public morals.”

Acknowledging the two religion clauses of the First Amendment and the provision in Article VI prohibiting religious tests, the Missouri state attorney quoted extensively from former Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story’s commentaries on these provisions where Story had observed that “The whole power over the subject of religion is left exclusively to the State governments, to be acted upon according to their own sense of justice and the State Constitutions.” The attorney continued with Story’s elaboration of this point:

“The Jew, the infidel, and the Christian are equal only in the national councils. The States may make any discrimination in favor of any sect or denomination of Christians, or in favor of the infidel and against the Christian. North Carolina has the right to exclude the Catholic from public trusts; and other States have the right, so long exercised, to deny ministers of all denominations a place in their legislative halls. Congress cannot establish a national faith, but where are the limitations on the powers of the States to do so?”

Decision on who can preach is church’s decision, attorney argues

The priest’s attorney recognized that the wording of the First Amendment, which referred specifically to laws by “Congress,” a branch of the national government, restricted only actions of that central government rather than actions of the states.

He nonetheless also thought that the First Amendment had announced “a great principle of American liberty, a principle deeply seated in the American mind, and now almost in the entire mind of the civilized world, that as between a man and his conscience, as related to his obligations to God, it is not only tyrannical but unchristian to interfere.”

Arguing less from First Amendment prohibitions than from general limitations that recognitions of inalienable rights impose on all governments, the attorney argued that “It is almost inconceivable that in this civilized day the doctrines contained in this constitution should be considered as within the legitimate sphere of human power.”

The attorney argued that churches should have as much liberty to choose how to proclaim the gospel as they always had: “Their decision is the high and unapproachable prerogative of the Church, under the guidance of its Redeemer, who alone is the searcher of hearts, and whose power it is to recall or reject whom he pleased.”

Supreme Court overturns conviction of priest

Justice Stephen Field wrote the majority opinion overturning Cummings’ conviction in a state circuit court for having taught and preached as a priest, a conviction that had been affirmed by the state supreme court.

Field, who was a strong advocate of laissez-faire economics and who would dissent from the high court’s restrictive reading of 14th Amendment rights in the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873), believed there could be little doubt that excluding an individual from the ability to practice a profession was a punishment that violated the inalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness that the American Founders had proclaimed.

He further believed that the law was a bill of attainder that violated due process by assuming without trial by jury that anyone who failed to take the oath must be guilty of an offense and that it imposed an ex post facto punishment for a past offense that was not punishable at the time it was committed. Although the provisions of the law were not part of the state’s criminal law, they had the same effect.

Dissenting justice argues states have authority on religious liberty

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase wrote the dissent in the accompanying case of Ex Parte Garland, 71 U.S. 333 (1866), which had involved a similar disqualification of an attorney. Chase did not think the law constituted either a bill of attainder or an ex post facto law because he did not believe that anyone was automatically entitled to be an attorney or a member of any other profession for this was “a privilege, and not an absolute right.”

Turning to Cummings, and the remarks that Cummings’ attorney had made with respect to “the inviolability of religious freedom in this country,” Chase pointed out that neither the provisions of the First Amendment nor the constitutional provision against religious test oaths applied specifically to the states.

Adding to arguments that Missouri had made against applying the First Amendment, Chase further cited the precedent in Permoli v. New Orleans (1845), which had upheld a limit on the places where a Roman Catholic priest could perform funerals within the city of New Orleans. In that case, the high court had stated that “The Constitution (of the United States) makes no provision for protecting the citizens of the respective States in their religious liberties; this is left to the State constitutions and laws; nor is there any inhibition imposed by the Constitution of the United States in this respect on the States.”

First Amendment rights eventually applied to states

In 1868, states ratified the 14th Amendment, which provided that state governments had to respect certain fundamental rights including those involving due process. Beginning with Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Supreme Court began recognizing that these due process rights included those in the First Amendment.

Today’s Supreme Court would almost certainly say the Missouri law as applied to either priests or educators violates the free speech and free exercise rights of the First Amendment as well as the bill of attainder and ex post facto law restrictions.

1866 case being cited as way Donald Trump could hold future office

The Cummings and Garland cases have received renewed attention (albeit for their statements regarding bills of attainder and ex post facto laws) in an article by professors William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen. They argue that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which denies the right of individuals who have violated their oaths to uphold the Constitution to hold public office, can be used to exclude former President Donald J. Trump and other office holders who they believe participated in an insurrection or rebellion on Jan. 6, 2001, at the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C., as they tried to obstruct proceedings related to certifying the presidential election results.

John R. Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.