In Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319 (1972), the Supreme Court established that claims of religious freedom by prison inmates should not be dismissed outright without, at the least, factual findings by trial courts.

Cruz claimed prison discriminated against Buddhist beliefs

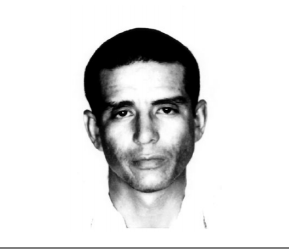

Fred Cruz, a Buddhist incarcerated in a Texas prison, claimed that prison officials had retaliated against him for sharing his religious beliefs with other inmates. He also charged that prison officials had denied him access to his religious adviser and in general discriminated against Buddhists by not making provisions for Buddhist inmates similar to those provided for Christian and Jewish inmates.

A federal district court granted the state’s motion to dismiss without holding an evidentiary hearing. The district court reasoned that the matters addressed in Cruz’s complaint — such as which inmates had access to the prison chapel — were best “left to the sound discretion of prison administrators.” The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed.

Court: Prisons must enforce constitutional rights of prisoners

On appeal, the Supreme Court issued a per curiam decision vacating the lower court decision and reinstating Cruz’s complaint by an 8-1 vote.

The Court recognized that federal courts generally should not “supervise prisons,” but also that courts must enforce the constitutional rights of all, including prisoners.

The justices reasoned that Cruz’s allegations, if true, did plead a cause of action under the First Amendment that should not have been summarily dismissed by the trial court.

Court cites previous ruling on prisoners’ religious freedom claim

The Court cited its decision in Cooper v. Pate (1964), which held that an inmate stated a constitutional claim when he alleged denial of the right to purchase religious publications because of his faith. “If Cruz was a Buddhist and if he was denied a reasonable opportunity of pursuing his faith comparable to the opportunity afforded fellow prisoners who adhere to conventional religious precepts, then there was palpable discrimination by the State against the Buddhist religion,” the Court wrote.

Justice Harry A. Blackmun concurred without writing an opinion, while in a short written concurrence Chief Justice Warren E. Burger agreed that the trial court should not have dismissed the entire lawsuit without at least conducting a hearing.

Burger believed that some of Cruz’s allegations bordered on the frivolous, writing, “There cannot possibly be any constitutional or legal requirement that the government provide materials for every religion and sect practiced in this diverse country.”

In dissent, Justice William H. Rehnquist reasoned that Cruz’s complaint failed to show that he was being punished for his religious beliefs and that his First Amendment rights were not violated just because Texas prison officials did not offer Buddhist services.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.