In 1961, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Sunday-closing blue laws on the basis that they serve the secular purpose of allowing families to be together at least one day a week (McGowan v. Maryland). But throughout most of U.S. history, states have upheld such laws on the basis that they were necessary to promote morality.

This is evident in the case of Commonwealth v. Wolf, 3 Serge. & Rawle 48, which was decided by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in 1817.

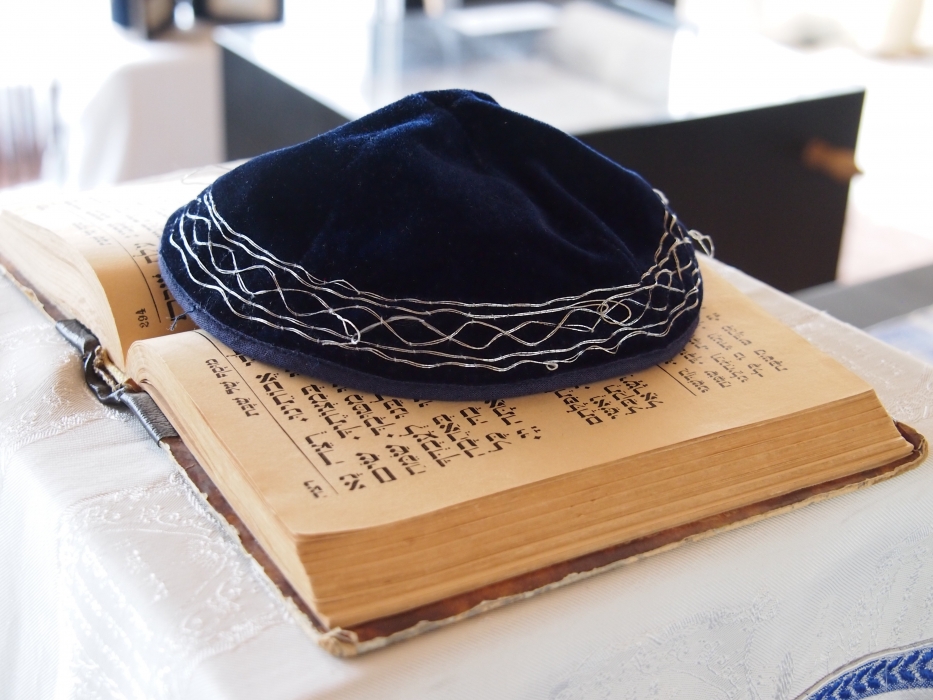

Jewish man fined for working on Sunday

Philadelphia Alderman Samuel Badger had fined Abraham Wolf, who was Jewish, $4 for violating a state law against working on Sunday. In addition to prohibiting cursing or swearing, the law punished breaches of the Sabbath, which consisted of “any worldly employment or business on the Lord’s day, commonly called Sunday, works of necessity and charity only excepted.” The state had adopted the law in 1794 “for the prevention of vice and immorality.”

Wolf had chosen instead not to work on the Jewish Sabbath, which is Saturday.

Wolf’s attorney based his defense on Article 9, Section 3 of the state constitution. Like other state constitutional provisions of its day, it provided that “All men have a natural and indefeasible right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own consciences. No man can of right be compelled to attend, erect or support any place of worship, or to maintain any ministry against his consent. No human authority can, in any case whatever, control or interfere with the rights of conscience, and no preference shall ever be given, by law, to any religious establishments or modes of worship.”

Wolf’s attorney suggested that some Jews might feel that the Biblical mandate to observe the Sabbath required that one work the other six days each week or might even find the idea of taking off Sunday, rather than Saturday, as “abhorrent” to their own religion.

Pennsylvania Supreme Court upholds ‘Sabbath’ law of majority religion

Essentially dismissing these arguments, Justice Jaspar Yeates tied the functioning of “any civilized government” to citizens’ reverence for “the sanctity of an oath” and “a future state of rewards and punishments for the deeds of this life.” It was accordingly, “of the utmost moment . . . that they should be reminded of their religious duties at stated periods; and the laboring part of the community must feel the institution of a day of rest as peculiarly adopted to invigorate their bodies for fresh exertions of activity.” Hence, the “rights of conscience” “was never intended to shelter those persons, who, out of mere caprice, would directly oppose those laws for the pleasure of showing their contempt and abhorrence of the religious opinions of the great mass of the citizens.”

Justice John Bannister Gibson concurred in the opinion. This shows that the court did not understand freedom of religion to exempt individuals from following legislation designed to support the religion professed by the majority. This was consistent with later U.S. Supreme Court opinions, such as the one upholding anti-polygamy laws in Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1879), that distinguished between the ability to regulate religiously motivated actions from that of dictating religious beliefs. Such decisions suggest that religious freedom in America has not been as robust as it has often been proclaimed to be.

This article was published April 18, 2022. John R. Vile is a Professor of Political Science and Dean of the University Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University and the author of “A Companion to the United States Constitution and Its Amendments.”