Clarence Darrow (1857–1938) was one of America’s most famous and controversial defense attorneys, known for his role in the Scopes monkey trial of 1925 and other major cases of his day.

He lived and practiced law during a period of unprecedented upheaval and profound change in the United States. The transition from a largely rural and agricultural society to an industrialized and urbanized nation created sharp contrasts between the wealthy and the new working-poor class.

Darrow considered the conditions the poor faced in the new industrial society inhuman and unjust. He took unpopular cases — representing labor-movement clients charged with violence, treason, and conspiracy — to give voice to “the weak, the suffering, and the poor” by defending their First Amendment rights to free speech, to a free press, and to petition the government (Darrow 1934: 32).

The legal and political machinery of the industrializing nation tended to favor corporations and stockholders over emerging labor unions and workers, and attempts to improve workers’ conditions were met with resistance.

Darrow thought conspiracy laws were unconstitutional

The unions’ demands sometimes resulted in violence against individuals and property, and they were viewed as a serious threat by the new capitalists, who feared that the labor movement had ties to international communism and might lead to anarchy. In response to the perceived risk and the “red scare” hysteria of the early 1900s, the government passed laws that, in effect, restricted advocacy of ideas considered incompatible with the existing order.

Darrow believed that such restrictions were unconstitutional. Of all the threats to freedoms of speech, of the press, and to gather and to petition the government, the most sinister, Darrow thought, was the increasing use of conspiracy laws to combat labor unrest and other forms of dissent.

Such laws both increased the potential severity of sentences and criminalized the discussion of or dissemination of information or ideas that were directed at improving the lot of the working class. In Darrow’s words, conspiracy was “the modern and ancient drag-net for compassing the imprisonment and death of men whom the ruling class does not like” (1934: 144).

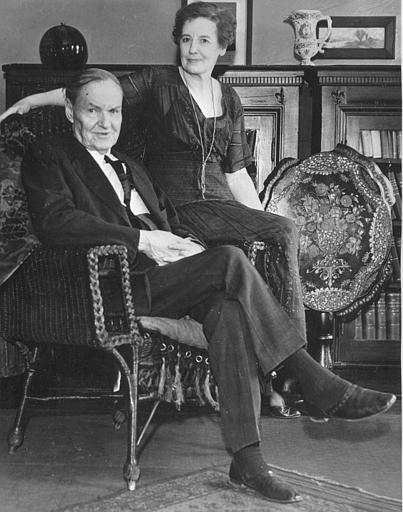

Lawyer Clarence Darrow is seen with his wife at his home in Chicago, Ill., on April 18, 1936, one day before his 79th birthday. (AP Photo, used with permission from The Associated Press.)

Darrow argues against government convictions in In re Debs

In 1895 Darrow had the chance to argue against conspiracy laws in front of the Supreme Court.

The American Railway Union, led by Eugene Debs, had struck for higher wages in 1894. Based on the strike’s ensuing violence and the disruption of the railways, a federal court granted the railroads an injunction that prohibited anyone from, among other things, encouraging workers to join the strike.

Debs and other union leaders were found guilty of violating the injunction, and a federal judge sentenced them to three months in jail.

Darrow appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, where he argued that Debs and the others had been convicted of doing and advocating what is lawful — organizing support for a union. They had not encouraged violence and had even cautioned their supporters to avoid any violent activity.

“If men could no do lawful acts because violence might possibly or reasonably result,” Darrow argued in In re Debs (1895), “then the most innocent deeds might be crimes. To make them responsible for the remote consequences of their acts would be to destroy individual liberty and make men slaves.”

The Supreme Court disagreed and upheld the sentences.

Darrow defends English anarchist’s speech before Supreme Court

Nevertheless, Darrow continued to seek opportunities to champion his cause before the Supreme Court, declaring the unconstitutionality of conspiracy laws that linked speech to potential or actual violent behavior, however distant the connection.

Clarence Darrow, left, and William Jennings Bryan speak with each other at the “monkey trial” in Dayton, Tenn. in 1925. Darrow was one of three lawyers sent to Dayton by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). They defended John T. Scopes, a biology teacher, in his test of Tennessee’s law banning the teaching of evolution. Bryan testified for the prosecution as a bible expert. (AP Photo. Used with permission from The Associated Press.)

In 1904 he again argued before the Court, attempting to prevent the deportation of John Turner, an English anarchist and union organizer who had been convicted of advocating the forceful overthrow of the U.S. government.

In United States ex rel. Turner v. Williams (1904), Darrow linked the right to abolish old governments, as written in the Declaration of Independence, with the First Amendment right of free speech. Once again, the Court disagreed with Darrow, and it upheld Turner’s deportation order.

In 1925 Darrow led the defense counsel employed by the American Civil Liberties Union in the Scopes monkey trial in Dayton, Tennessee.

In the case, a high school biology teacher was charged with violating a state law that forbade teachers from presenting the theory of evolution in the classroom. During the trial, Darrow subjected William Jennings Bryan, a member of the prosecution, to a withering cross-examination that exposed difficulties with Bryan’s views. Although First Amendment issues were not raised at the time, the Scopes trial has since become a landmark legal symbol.

Darrow, a brilliant defense attorney, considered the First Amendment to be the written guarantee that the government could place “no fetters on thought and actions and dreams and ideals of men, even the most despised of them’ ” (Weinberg 1987: 291).

Alex Aichinger is a former professor at Northwestern State University in Louisiana. He has also contributed to American Constitutional Law Volumes I and II. This article originally published in 2009.