The chilling effect doctrine is the concept of government unduly deterring free speech and association rights through laws, regulations or actions that appear to target activities protected by the First Amendment.

For example, government actions have a chilling effect if people think the government may take action against them because of their speech or associations, so they refrain from such speech or associations out of caution.

The chilling effect doctrine is closely related to the overbreadth doctrine, which prohibits the government from casting too wide a net when regulating activities related to speech and expression.

The origin of the chilling effect doctrine

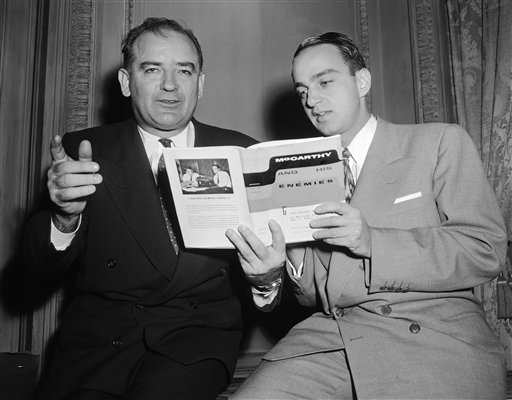

The Supreme Court developed and explained the chilling effect doctrine in several opinions during the McCarthy era involving legislation and regulations aimed at suspected Communists and so-called subversives.

In Baggett v. Bullitt (1964), the court struck down loyalty oaths requiring Washington state employees to affirm that they were not members of alleged subversive organizations and requiring teachers to swear to promote “undivided allegiance to the government of the United States.”

In ruling that these provisions violated the First Amendment rights of employees, who would be unable to determine what they were swearing to, the court asserted that “the threat of sanctions may deter … almost as potently as the actual application of sanctions.”

In Lamont v. Postmaster General (1965), the Supreme Court struck down a postal regulation requiring individuals who wished to receive Communist literature to sign up at the post office. Although the program included no sanctions against recipients of Communist literature through the mail, the court said it would “chill” individuals who wanted the material but were afraid to make their wishes known to the government.

The chilling effect of such governmental requirements was exacerbated by widespread knowledge that under the guidance of Director J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI had gathered dossiers recording the political beliefs and associations of millions of Americans suspected of “un-American” views and activities.

Court: Requiring Communist groups to register had chilling effect on association rights

The chilling effect doctrine reached its zenith in Dombrowski v. Pfister (1965), a case involving the Louisiana Subversive Activities and Communist Control Law and Communist Propaganda Control Law, which the state was using to require civil rights groups to register as Communist-front organizations.

In a groundbreaking opinion written by Justice William J. Brennan Jr., the Supreme Court ruled that not only was the Louisiana law unconstitutional, but that the federal courts could enjoin the state of Louisiana from bringing prosecutions under it.

The Supreme Court rejected the notion that injunctions were unavailable in situations involving criminal prosecution because defendants always had the right of appeal if convicted under unconstitutional statutes. Although an appeal might provide adequate protection for the rights of the criminal defendants, Brennan wrote that such an appeal would not protect the First Amendment rights of third parties who might be deterred from speaking out in the interim.

Anti-war protesters lost claim that surveillance had chilling effect on their speech

Chilling effect as an independent reason for challenging government action suffered a devastating setback in Laird v. Tatum (1972), in which a new Supreme Court majority dismissed a case brought by civil rights and anti-war activists seeking an injunction against the army’s Domestic Intelligence Program, which had compiled dossiers on political protesters, including the plaintiffs.

The Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the plaintiffs could not base a challenge to government policy on the chilling effect it would have on third parties and that the plaintiffs themselves were obviously not chilled since they had been willing to identify themselves publicly by filing suit.

This article was originally published in 2009. Frank Askin is a retired Professor Emeritus at Rutgers University, where he taught election law and constitutional law for 50 years. He was the longest-serving general counsel in the history of the American Civil Liberties Union. His most lasting legal accomplishment was having New Jersey recognize homeowner associations as quasi-governmental agencies, requiring them to recognize free speech rights for their residents.