Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Burstyn v. Wilson (1952) that blasphemy is not a recognized exception to First and Fourteenth Amendment protection for freedom of speech, prior state supreme courts had upheld such laws, largely on the basis that they were designed to promote public peace and maintain good order.

This included in 1811 in People v. Ruggles in New York; in 1837 in State v. Chandler in Delaware; and in 1838 in Commonwealth v. Kneeland in Massachusetts.

Even as late as 1887, a jury in a trial court in New Jersey came to a similar decision in the case of Charles B. Reynolds. And although the jury upheld Reynold’s fine for blasphemy, the trial court record offers a detailed look into the passionate arguments against blasphemy laws by noted attorney Robert Ingersoll.

Local jury in New Jersey upholds blasphemy fine in 1887

After being essentially run out of town in Boonton, Reynolds, a one-time Methodist minister who was described as “an accredited missionary of freethought and speech,” had proceeded to Morristown where he had published a pamphlet entitled “Blasphemy and the Bible” outlining his religious view as well as a satirical cartoon entitled “Casting pearls before swine” of his Boontown experience. He was fined $25.

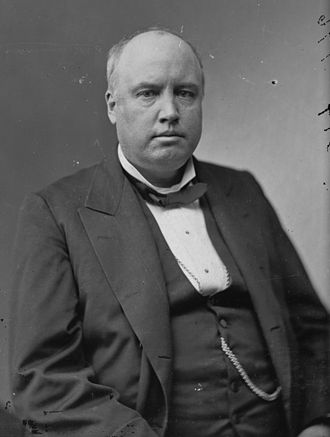

After the judge had instructed jurors that Reynolds had committed blasphemy, a local jury had upheld the fine, despite pleas that Reynolds’ speech was protected by the state constitution. Robert Ingersoll, one of the nation’s leading freethinkers and orators, had defended Reynolds at trial, and the publication of his remarks stood as one of the strongest arguments against blasphemy laws until the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Burstyn.

Ingersoll advocated ‘intellectual hospitality’

Ingersoll described the attempt to punish Reynolds as an effort “to put a padlock on the lips.” He excoriated organized religions and denominations for advocating freedom of speech when they were in the minority and seeking to suppress it when they were in power. By contrast, he advocated what he described as “intellectual hospitality.” The definition of blasphemy varied from one country to another depending on the majority religion, but the U.S. had attempted to eliminate such variation by divorcing church and state and allowing human conscience to flourish.

He argued that individuals should have the same right to read the Bible and conclude that it contained falsehoods as they should have to read it and agree with it. In his argument before the jury, Ingersoll himself pointed to biblical passages that he thought were problematic.

As long as the U.S. was willing to admit adherents of rival faiths as citizens, then it should permit them to agree or disagree with Christianity as their convictions warranted. State judgments on religious matters were not “infallible.” History was replete with examples of individuals who advocated religious and scientific doctrines that, once rejected, were now considered to be established facts.

Ingersoll attacked blasphemy laws

Ingersoll associated laws against blasphemy with the ignorance and intolerance of past ages.

He argued that:

“Blasphemy is what an old mistake says of a newly discovered truth.

Blasphemy is what a withered last year’s leaf says of this year’s bud.

Blasphemy is the bulwark of religious prejudice

Blasphemy is the breastplate of the heartless.”

Countering arguments that blasphemy laws were a necessary way to promote “the public peace,” Ingersoll described it as living “on the unpaid labor of other men,” of enslaving others, of enslaving human minds, of denying what one believes to be true, of attempting to gain “the applause of the ignorant and superstitious mob,” of persecuting the “intelligent few, at the command of the ignorant many,” of imprisoning individuals for their beliefs, of teaching about an eternal hell, of violating conscience, and of rendering unjust verdicts.

Ingersoll appealed to New Jersey’s previous policy of toleration

Ingersoll noted that repression based on religious views, which had been common in New England, had not previously been practiced in New Jersey and was contrary to its previous policy of toleration. He believed that the statute under which Reynolds had been prosecuted abridged the provision in the state constitution (the First Amendment had not yet been applied to the states) guaranteeing freedom of speech and further denied that the words that Reynolds had spoken had even risen to the level of blasphemy.

Ingersoll questioned why anyone would want to resurrect a law that the state had not previously applied. He further argued that Christians on the jury would better exemplify their faith if they recognized Reynolds’ liberty to say what he believed. After evoking the spirit of Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, and Lincoln, Ingersoll ended with the hope that “it will never be necessary again for a man to stand before a jury and plead for the Liberty of Speech.”

This article was published May 2, 2022. John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment.