In Cameron v. Johnson, 381 U.S. 741 (1965) and 390 U.S. 611 (1968), the Supreme Court first remanded the case — concerning allegations that a Mississippi anti-picketing statute was overly broad and was designed to discourage civil rights activities — and then affirmed a lower court’s dismissal of injunctive relief.

District court refused to enjoin picketing law

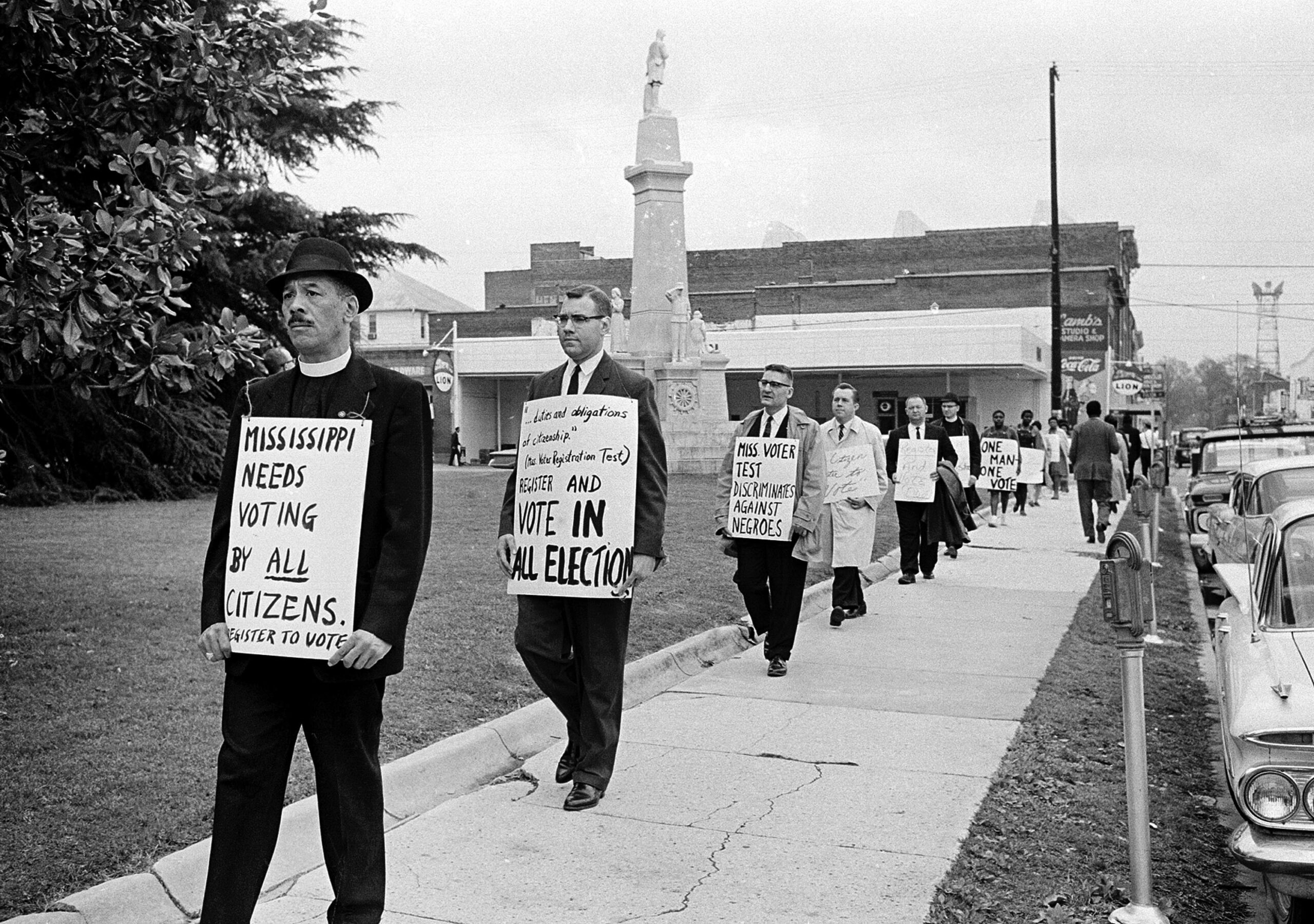

In 1965 the Supreme Court had remanded the case after a federal district court refused to grant an injunction against the law, which made it unlawful for individuals engaged in picketing “to obstruct or interfere with free ingress or egress to and from any public premises, State property, county or municipal courthouses, city halls, office buildings, jails, or other public buildings or property.

Supreme Court said district court needed to reconsider case

The Court said the district court needed to reconsider the case in light of Dombrowski v. Pfister (1965), which permitted an injunction against subversion laws in Louisiana that were being used to suppress First Amendment activities.

Justice Hugo L. Black authored a dissenting opinion joined by John Marshall Harlan II and Potter Stewart.

Black argued that the law was not overly broad, vague, or unconstitutional on its face. He also did not think that Dombrowski applied, and therefore saw no reason for the district court to reconsider its decision in light of this precedent.

He noted that Cox v. Louisiana (1965) had upheld state power to regulate picketing and parading “even though [they are] entwined with expression and association.” States had the right to maintain “an atmosphere of peace and quiet.”

In a separate dissent, Justice Byron R. White also questioned the applicability of the Dombrowski precedent and denied that the Mississippi law seemed overly broad or vague.

Supreme Court upheld law

The case reappeared before the Supreme Court in 1968.

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote the opinion for the 7-2 decision affirming a lower court’s dismissal of injunctive relief. The Court agreed that Dombrowski did not warrant invalidation of the Mississippi law, which was understood to apply only to blocking access to public facilities.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Abe Fortas, joined by William O. Douglas, agreed that the law was not facially unconstitutional, but thought the circumstances of the law’s adoption and its application to individuals registering voters demonstrated that the state was not engaged in good-faith enforcement and that the law was part of “a deliberate plan to put an end to the voting-rights demonstration.”

Younger v. Harris (1971) subsequently limited the scope of the Dombrowski decision.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.