The ruling in Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S.37 (1971), limited the occasions in which the Court would intervene to enjoin state prosecutions in First Amendment cases and narrowed an earlier ruling in Dombrowski v. Pfister (1965) on this matter.

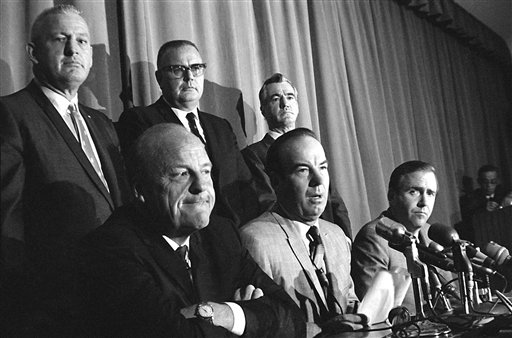

California district attorney Evelle J. Younger had initiated a prosecution against John Harris Jr., under the California Criminal Syndicalism Act, even though the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) had suggested that the decision in Whitney v. California (1927), which upheld this law, was no longer constitutional. Harris was joined by others who alleged that his prosecution would have a chilling effect on their own exercise of First Amendment rights.

Supreme Court: Federal government could not intervene to prevent prosecution

The decision, written by Justice Hugo L. Black, ruled that all claims other than Harris’s were “imaginary or speculative.”

Justice Black argued that since 1973 Congress had “manifested a desire to permit state courts to try state cases free from interference by federal courts.” He associated this principle with that of “‘comity,’ that is, a proper respect for state functions, a recognition of the fact that the entire country is made up of a Union of separate state governments, and a continuance of the belief that the National Government will fare best if the States and their institutions are left free to perform their separate functions in their separate ways.”

He called this “Our Federalism.” Accordingly, the only time that the United States should enjoin state officials from criminal actions should be “under extraordinary circumstances where the danger of irreparable loss is both great and immediate.”

Although Dombrowski v. Pfister had permitted injunctions in some circumstances, Black did not think these injunctions applied in this case.

Black said judiciary did not have power to pass judgment on laws before courts called to enforce them

He observed that even federal intervention would not eliminate the chilling effect that the uncertainty of state laws might pose and further observed that courts had upheld state legislation against claims that it chilled speech, when such laws were not directly aimed at such speech and where any effects on First Amendment rights were incidental.

Black observed that the judiciary had a role in genuine cases and controversies but that this did “not amount to an unlimited power to survey the statute books and pass judgment on laws before the courts are called upon to enforce them.”

Justices Potter Stewart and William J. Brennan Jr. authored concurring opinions, noting that there was no evidence of bad faith or harassment in this case.

Douglas dissented, found California Criminal Syndicalism Law unconstitutional on its face

In his dissent, which also applied to the companion decision in Boyle v. Landry, Justice William O. Douglas wrote that Dombrowski “governs statutes which are a blunderbuss by themselves or when used en masse—those that have an ‘overbroad’ sweep.”

He would have enjoined state prosecution in this case because he thought that the California Criminal Syndicalism Law was “unconstitutional on its face,” noting that Harris’s “crime” had been that of “distributing leaflets advocating change in industrial ownership through political action,” rather than “through the use of bullets, bombs, and arson.” Douglas believed that the Civil War and the post-bellum amendments had significantly modified the federal system and that the Court needed to recognize such changes. He concluded that he could “see no reason why these appellees should be made to walk the treacherous ground of these statutes. They, like other citizens, need the umbrella of the First Amendment as they study, analyze, discuss, and debate the troubles of these days.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.