In Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665 (1972), the Supreme Court ruled that freedom of press did not create a constitutional privilege protecting reporters from having to testify in grand jury proceedings about the identity of news sources or information received in confidence. The case was consolidated with In re Pappas and United States v. Caldwell.

Reporters refused to answer grand jury questions regarding confidential sources

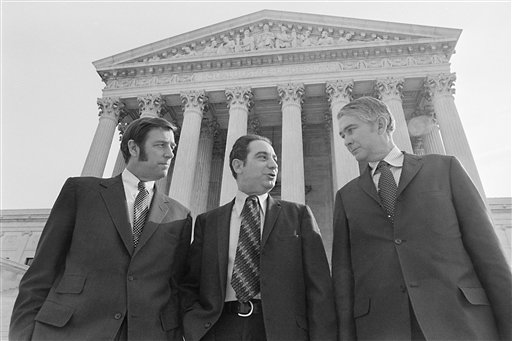

Newspaper reporter Paul Branzburg of Kentucky refused to answer questions before grand juries regarding stories that he had authored and published involving illegal drugs. Journalists Paul Pappas of Massachusetts and Earl Caldwell of California also refused to appear before grand juries to answer questions about illegal activities they might have observed in writing about the Black Panthers.

All three reporters had promised their sources confidentiality and feared that revealing their sources would compromise their effectiveness as reporters.

Court said case did not involve core First Amendment values

Writing for the majority in the 5-4 decision, Justice Byron R. White clarified that this case did not involve the core values of the First Amendment. The reporters had not been required to reveal their sources nor had they been prevented from using any source of information, confidential or otherwise.

Further, the reporters had not been threatened with tax for publication or any penalty, criminal or civil, related to the content of a publication. Rather, the case concerned whether reporters’ obligation to be subject to grand jury subpoenas — by answering questions relevant to criminal investigations as all other citizens are required to do — would so burden newsgathering that they should be granted a privileged position.

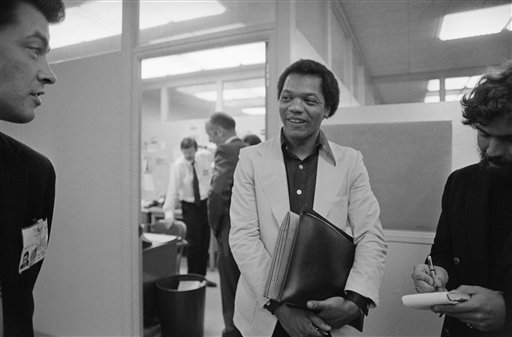

In this photo, Earl Caldwell, NY Times reporter, arrested at Angela Davis trial for investigation of marijuana possession, leaves the office of Lt. Don Tamm, background, after being released on his own recognizance in San Jose, Calif., March 7, 1972. Caldwell was one of the reporters involved in the cases surrounding Branzburg v. Hayes. (AP Photo/Robert W. Klein)

Laws that advance substantial public interests but burden the free press have been upheld

Having established the primary question before the Court, White noted that the First Amendment does not invalidate all incidental burdens on the press that may be the result of generally applicable laws.

Instead, he explained, laws that advance a substantial public interest have been upheld even when they impose a burden on a free press; such laws include those regulating the requirements of the National Labor Relations Act, libel, the right of access to government information, and the need to protect a defendant’s right to a fair trial.

Court said they were unwilling to protect reporters from testifying before grand juries

Observing that a majority of the states had failed to protect reporters from having to testify before grand juries, White announced that the Court was also unwilling to do so. Noting that both the common law and American history frowned upon those who concealed crime by not reporting felonies, White did not anticipate that the ruling would have much impact on newsgathering.

Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. penned a short concurrence that almost read like a dissent. He emphasized that government officials could not harass journalists with bad faith investigations. He also wrote that “if the newsman is called upon to give information bearing only a remote and tenuous relationship to the subject of the investigation, or if he has some other reason to believe that his testimony implicates confidential source relationships without a legitimate need of law enforcement, he will have access to the court on a motion to quash, and an appropriate protective order may be entered.”

Dissenters thought reporters should only have to testify when there is a compelling government interest

Justice Potter Stewart’s dissent, which Justices William J. Brennan Jr. and Thurgood Marshall joined, suggested that reporters should have to testify before grand juries only when the government shows a compelling interest in the testimony.

Stewart reasoned that the government must establish the following three elements before compelling a journalist to testify:

- “(1) show . . . probable cause to believe that the newsman has information that is clearly relevant to a specific probable violation of law;

- (2) demonstrate that the information sought cannot be obtained by alternative means less destructive of First Amendment rights;

- and (3) demonstrate a compelling and overriding interest in the information.”

These three elements formed the blueprint for reporter shield laws adopted by many states. Justice William O. Douglas penned a separate dissent.

This article was originally published in 2009. Tom McInnis earned a Ph.D. from the University of Missouri in Political Science in 1989. He taught and researched at the University of Central Arkansas for 30 years before retirement. He published two books and multiple articles in the area of civil liberties and the American legal system.