In Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000), the Supreme Court ruled that the Boy Scouts of America had the expressive association right to revoke the membership of an assistant scoutmaster after he publicly announced his sexual orientation by leading a gay group at Rutgers University.

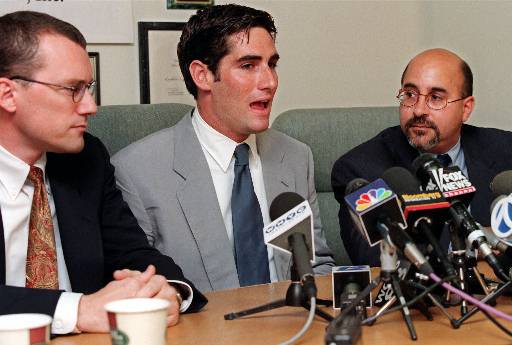

Dale’s Boy Scout membership revoked after he came out as homosexual

The Scouts revoked James Dale’s membership on the basis that the “the Boy Scouts ‘specifically forbid membership to homosexuals.’ ” Dale filed a complaint against the Scouts in New Jersey state court, alleging that this action violated the state’s public accommodations law.

Boy Scouts said they had First Amendment right to refuse employment to homosexuals

The Boy Scouts responded that the First Amendment granted the organization the right to expressive association, allowing the Scouts to refuse employment to individuals who violated its moral code, because employing such individuals would impinge on the Scouts’ ability to impart that code to its members.

The New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in favor of Dale, holding that the forced inclusion of Dale would not significantly affect the Scouts’ ability to disseminate its message, as the Scouts did not associate to promote the message that homosexuality is immoral. The court added that any infringement on the Scouts’ right to expressive association was justified by the state’s compelling interest in preventing discrimination.

Court ruled in favor of the Boy Scouts

The New Jersey Supreme Court’s opinion was consistent with the expressive association doctrine the U.S. Supreme Court had developed in Roberts v. United States Jaycees (1984) and subsequent cases. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, reversed the lower courts’ holdings in a 5-4 opinion written by Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist.

The Court determined that Dale’s forced inclusion in the Scouts would significantly affect the organization’s right of expressive association. The Court found that groups do not have to associate for the purpose of disseminating a specific message to be entitled to First Amendment protection.

Further, even if the Boy Scouts discourages leaders from disseminating views on sexual issues, this does not negate the sincerity of its belief that homosexuality is immoral. Finally, the First Amendment does not require that every member of a group agree on every issue in order for the group’s policy to be “expressive association.”

Consistent with Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s concurring opinion in Roberts, the Court seemed to limit its analysis to noncommercial organizations like the Boy Scouts; the relevance to commercial organizations is unclear.

Court loosely applied compelling interest test

The Court proceeded to apply the compelling interest test, which the Roberts line of cases suggested almost always justified antidiscrimination laws challenged on expressive association grounds. In Dale, by contrast, the Court gave the test short shrift, stating simply that “the state interests embodied in New Jersey’s public accommodations law do not justify such a severe intrusion on the Boy Scouts’ rights to freedom of expressive association” and leaving no doubt that the test had been repudiated.

Dissenters thought Boy Scouts’ message did not warrant expressive association protection

The four dissenters did not argue for the use of the Roberts-style compelling interest test. Rather, they argued that the Boy Scouts’ message against homosexuality was too vague, unpublicized, and irrelevant to the organization’s core mission to warrant expressive association protection.

Dale started toward recognition of expressive association as First Amendment right

Dale marked a substantial step toward the recognition of expressive association as a full-fledged First Amendment right with the same weight as the general right of free speech, at least for noncommercial associations.

Roberts and its progeny had treated expressive association as a second-class right, which could be infringed upon in most instances due to the Court’s narrow definition of an association’s expressive interests and the nature of the compelling interest test.

Dale, in contrast, held that the expressive association right could be asserted by an organization even though the organization does not associate for the purpose of expressing a particular message, propounds that message only implicitly, and tolerates dissenting views. Moreover, under Dale the courts will skeptically review governments’ claims that their invasions of expressive association rights serve interests sufficiently compelling to justify those invasions.

Scouts later lifted ban on openly gay members and leaders

In 2013, the Scouts lifted its ban on openly gay youth members. In 2015, Robert Gates, the former Secretary of Defense who was then serving as president of the Boy Scouts, announced that the Scouts were also lifting the Scout ban on gay leaders and leaving the issue to local chapters.

Some theologically conservative churches subsequently withdrew their sponsorship from such chapters, but others remained or returned after the Scouts continued to allow local chapters to set their own policies on the matter.

This article was originally published in 2009. David E. Bernstein is a university professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School, George Mason University, where he teaches constitutional law, among other things. He is the author of You Can’t Say That! The Growing Threat to Civil Liberties From Antidiscrimination Laws (Cato Institute 2003).