Birth control, or contraception, is a practice, material or device by which sexual intercourse can be rendered incapable of producing a pregnancy. Throughout history, women and men have practiced birth control in a wide variety of ways. Only in the last two centuries, however, has birth control become a matter of public debate. Speaking and writing about birth control have not always received strong First Amendment protection.

Speech about birth control was once illegal

Largely scorned and even condemned by public officials (President Theodore Roosevelt referred to it as “suicide of the race”), birth control was once treated as immoral and obscene by lawmakers. The 1873 Comstock Act, a federal law designed to prevent the distribution of immoral material, was used to censor communication about birth control, thereby placing medical advice and pornographic literature on the same plane. The well-known feminist Margaret Sanger, an early advocate of birth control, was arrested in 1929 after giving a speech about its practice. Sanger also faced criminal charges for writing and publishing about birth control and women's health.

Even though individual states eventually began to allow birth control clinics, many of them publicly funded, the courts did not rule until much later that communication about the subject was protected.

Court: State must have compelling reason to outlaw birth control

As the U.S. culture began to change, especially after the development of an oral contraceptive in the 1960s, opposition to birth control in general was heard infrequently except from some religious institutions, especially the Roman Catholic Church.

Meanwhile, Connecticut, a state with a largely Catholic population, had a rarely enforced law on its books that completely outlawed birth control. In the strange but important case of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the state must have compelling reasons for outlawing birth control, finding that there was a fundamental right to privacy, which included the right of married couples to control their fertility. Justice William O. Douglas delivered the opinion (7-2) of the Court in which the First Amendment was implicated only tangentially, as part of the constellation of rights in the Third, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and, most important, 14th amendments, the penumbras of which create a zone of privacy that the government dare not enter lightly.

Seven years later, in Eisenstadt v. Baird (1972), the Court further extended the right to birth control by striking down on equal-protection grounds a Massachusetts law criminalizing the distribution of birth control to unmarried persons. The Court again refused to base its decision on the First Amendment, even though Justice Douglas urged it to do so in his concurrence.

In 1977, the Supreme Court ruled that advertisements of contraceptives were protected by the First Amendment as speech and could not be outlawed. This photo shows William Baird, birth control and abortion crusader, displaying a board he would use on college lecture tours showing contraceptive devices. He was indicted in Wisconsin on charges of another board he also would use that showed implements for inducing abortion, including a knitting needle. (AP file photo)

Court extended First Amendment protection to contraceptive advertising

It was not until 1977 that the Court squarely addressed the First Amendment implications of birth-control information. In Carey v. Population Services International (1977), the Court extended First Amendment protection to advertisements of contraceptives. A corporation that advertised contraceptives in periodicals had challenged a New York statute prohibiting advertisements and displays of such products. New York based its law on the claims that advertisements of contraceptive products could be offensive and embarrassing and that permitting them would legitimize sex among young, unmarried people.

The Court rejected both bases as insufficient to support a restriction on First Amendment rights. It said that, short of obscenity, no speech may be suppressed on the grounds that it may offend some, citing Cohen v. California (1971). It also noted that the state could not demonstrate that advertising birth control affected the sexual behavior of minors. Thus the statute suppressed protected consumer information on contraceptives and so was a violation of First Amendment rights.

Later, the Court extended the Carey protection to advertisements and products sent to consumers through the mails. In Bolger v. Young’s Drug Products Corp. (1983), the Court held that federal restrictions on the free flow of truthful information on contraception constitutes a basic constitutional defect within the meaning of the First Amendment, regardless of the strength of the government’s interest.

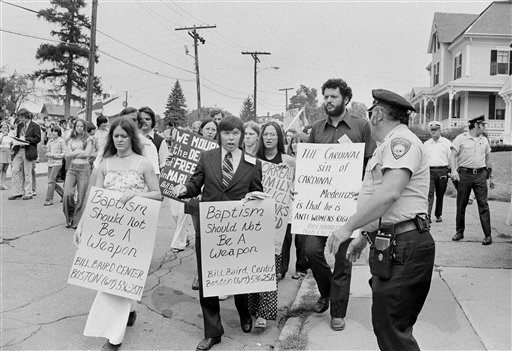

As the U.S. culture began to change, especially after the development of an oral contraceptive in the 1960s, opposition to birth control in general was heard infrequently, except from some religious institutions, especially the Roman Catholic Church. In this photo, birth control advocate Bill Baird, center, and Carol Morreale, left, as they led a demonstration outside the Immaculate Conception Church, Aug. 18, 1974 in Marlboro, Mass., protesting the denial of the baptismal sacrament to 3-month-old Nathaniel Morreale. Carol Morreale, the child’s mother has publicly advocated that women be given the right to choose whether they will have an abortion. (AP Photo)

The right to refuse to dispense birth control is being debated

Today, a person’s right to obtain and use birth control is still being challenged in a variety of ways, some of which have First Amendment implications. One interesting turnabout is the claim by some pharmacists, citing First Amendment freedom of religion, of a right to refuse to dispense birth control.

Yet another example is Catholic Charities of Sacramento, Inc. v. Superior Court (2004) in which the California Supreme Court rejected First Amendment challenges to the state’s compulsory contraceptive health insurance coverage law. Catholic Charities, as a religious employer whose tenets of faith oppose birth control, claimed a constitutional right to refuse such insurance. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to review the decision.

This article was originally published in 2009. James L. Walker (1942-2019) taught political science at Wright State University for 33 years.